|

19 thoughts on "touch grass"

Agrostology, hating lawns, not hating lawns, a visit to the sod farm, more Cuttings

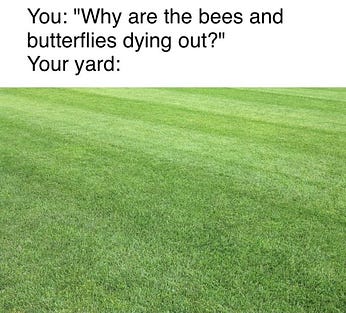

Nowadays, when an online fight spins out of control, devolving into inanity or insanity, it feels inevitable that someone will reply “touch grass,” or even just post an image of a lawn.

But … what is the grass are we talking here? One of the first things you learn about grass is that there is no simple just grass.

Agrostology is the branch of botany dedicated to grasses. If you read the work of agrostologists, they will note that grasses are the most important plants on earth. “There may well be more individual grass plants than there are all other vascular plants combined!” — from Agrostology: An Introduction to the Systematics

Think about it, though. What are the most important crops in the world? Wheat? Grass. Rice? Grass. Maize? Grass. We could go on: sorghum, rye, oats, millet. The cereals alone provide a huge chunk of the calories that power human life.

But what do animals raised for meat often eat? You guessed it. Apparently there is an old saying: “All flesh is grass.” Kinda creepy tbh, but we not only touch grass all the time, we are grass.

But that’s not what internet people are talking about, right? They are thinking about lawns, your bermuda grass, your fescues, your Kentucky bluegrass. “Covering a total area roughly the size of the state of Iowa, the lawn is one of the largest and fastest growing landscapes in the United States. The lawn receives more care, time, and attention from individuals and households than any other natural space.” That’s from Lawn People by Paul Robbins, a book about “the North American lawn… its ecological characteristics and its political economy.”

Lawn grasses are plants made for sitting on. Can’t say that about many plants.

Not everyone agrees you should sit on them, of course. Barbara McClintock, legendary biologist, told her biographer, “Every time I walk on grass I feel sorry because I know the grass is screaming at me.” (sorrysorrysorryoopsorry)

Why can you mow grass? This is one reason grass is so good for sitting on. And it has to do with the placement of the “meristem,” the part of the plant where upward growth occurs. The meristem in a grass is low to the ground, so you can cut the top off without killing the plant.

Many plant people detest lawns. Suburban, environmentally abhorrent, homogenizing, boring, puritanical, even sexless. You want an elegant evisceration of the lawn? You can’t do much better than Michael Pollan’s 1989 essay: “Why Mow? The Case Against Lawns.” He writes: “Unlike every other plant in my garden, the grasses were anonymous, massified, deprived of any change or development whatsoever, not to mention any semblance of self-determination. I ruled a totalitarian landscape.”

Grass is mass. It’s hard to get to know an individual grass plant. I spent some time rooting around in the yard, trying to see them one from the other. Where does one end and another begin? Eventually, I focused in on this one, which is quite beautiful.

Another fire Pollan diss: “And since the geography and climate of much of this country is poorly suited to turfgrasses (none of which are native), [a classic lawn] can’t be accomplished without the tools of 20th-century industrial civilization, its chemical fertilizers, pesticides, herbicides, and machinery. For we won’t settle for the lawn that will grow here; we want the one that grows there, that dense springy supergreen and weed-free carpet, that Platonic ideal of a lawn we glimpse in the ChemLawn commercials, the magazine spreads, the kitschy sitcom yards, the sublime links and pristine diamonds. Our lawns exist less here than there; they drink from the national stream of images, lift our gaze from the real places we live and fix it on unreal places elsewhere. Lawns are a form of television.”

There are cruder versions of the arguments, of course.

It’s hard to counter the arguments against big expanses of lawn, especially in dry places like California. There are good alternatives, and incentives to get people to pull out their turfgrass and put in drought tolerant, native plant gardens. I know.

But I should admit that a few years ago, I installed little green pools of sod. I rolled it out in those cute little sections and cut them into shape with a hooked knife.

You ever been to a place where they grow sod? I went to one in Patterson, maybe 90 minutes southeast of Oakland. It was very flat and very hot. Great fields of grass were watered by gushing sprinklers. They had some kind of machine, a sod cutter. I remember it as Rube Goldbergian, guys walking alongside it, scooping up the sod for sale. But underneath the sod lay earth that looked about as alive as an outdoor basketball court. You drive your car out onto it, and the guys load the rolls of life into the trunk right there. Environmental historian Brian Black might call this place “a sacrificial landscape.”

But have you ever seen a bunch of kids playing on a patch of grass on a warm summer evening, smudged with dirt, legs stained, rolling on the glory of tiny blades? Like a beach, a patch of grass is an activity for children. The sheer physical possibility of it invites them to play. I’ll look at photos of our tiny patch of grass and like seven kids are doing different things on it all at once. Their detritus is mysterious—tiny sticks, random balls, a hula hoop, a leaf collection, the soft indentations of their bodies on the grass. What can you do looking at a scene like that (especially as the sun dips behind the house and it is suddenly cool), but think… This is the essence of a decent life, ordinary and chaotic.

That is to say, I cannot hate a lawn, even if I should.

Does going outside and touching grass make us better people? Perhaps not, but it can short-circuit the attentional dynamics of modern life. The grass cares not that someone is wrong on the internet. It has its own problems to deal with, like you walking on it and sitting down and plucking a blade to consider between your fingers.

CUTTINGS

The digital community we’re building at KQED Forum is rounding into shape. We’re going to let more people into the beta test soon. If you’re interested in Bay Area civic life, plants, community, etc, come join!

Oakland artist Kija Lucas has new limited-edition prints and scarves available. For the scarves, check out Tessuto Editions, and you can email info@for-site.org for more information on the prints.

Friend of the Club William Thomas Okie wrote a fantastic essay on another kind of grass, broomsedge: “Broomsedge was uncultivated, the plant that came up when you didn’t plant anything, the quintessential unintended landscape.” He’s at work on a book tentatively titled, Old Fields: A History of the American South in Six Ordinary Plants. Extremely Oakland Garden Club!

I was quite taken by Chaebin Yoon’s student project about foraging acorns to make dotorimuk, Korean acorn jelly. “did they know / those birds / as they left /

that it would be the last time?” Yoon made it in a photography course at Sac State co-taught by Eliza Gregory. You might also love Gregory’s project about holding and being held by place, [placeholder].This is a fascinating little reflection by the UC Botanical Garden on the chemical complexity of nectar through time: “Although nectar is often replaced daily, as the flower ages the nectar quality and quantity can change. The changes are often a consequence of either the visiting pollinators adding microbes, or as the weather changes.” (I couldn’t help but thinking of the Pujol mole.)

Friend of the Club Wendy MacNaughton has a new book out, How to Say Goodbye. It’s not about plants, but it is profound. Who knows when you might need it? Might as well buy it now.

You're currently a free subscriber to oakland garden club. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription.