|

|

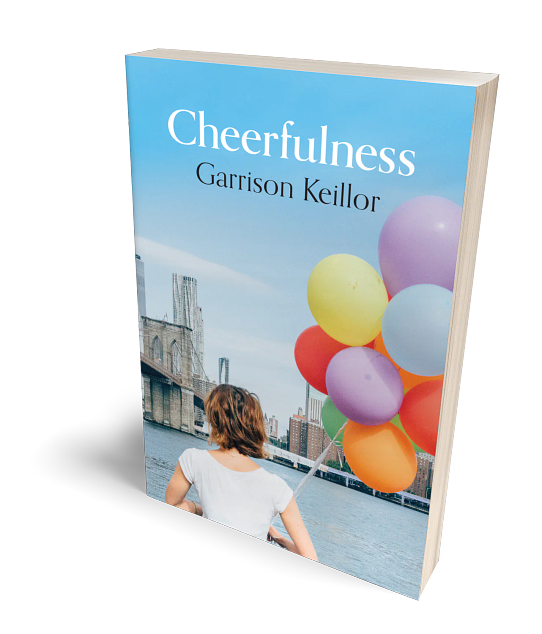

We have had a very “cheerful” response to Garrison’s latest book! So cheerful that we will ship unsigned copies free for a limited time. Order today so that you can become more cheerful soon!

BUY NOW > > >

Behind his self-described “gloomy” visage, Garrison Keillor is a cheerful man. And he’s sharing his thoughts on the benefits of a buoyant demeanor in his new book, Cheerfulness.

“Cheerfulness is a choice,” he tells us. “Adopting cheerfulness as a strategy does not mean closing your eyes to evil; it means resisting our drift toward compulsive dread and despond.”

The theme weaves its way through Keillor’s thoughts on friends, family, work, marriage (“Marriage is the true test of cheerfulness — to make a good life with your best informed critic.”). Cheerfulness shows up in small acts of kindness and heroic acts in the face of adversity. “It’s not the be-all and over-all, the ultimate or consummate and uttermost. It’s a useful tactic to get your head on straight and go where you need to go and not wind up in the swamp.”

Funny, poignant, thought-provoking, whimsical — Cheerfulness is sure to charm longtime Keillor fans and those just getting to know the writing of this much-admired author.

Here is the first chapter for your enjoyment!

1. CHEERFULNESS

It’s a great American virtue, the essence of who we are when we’re cooking with gas: enthusiasm, high spirits, rise and shine, qwitcher bellyaching, wake up and die right, pick up your feet, step up to the plate and swing for the fences. Smile, dammit. Dance like you mean it and give it some pizzazz, clap on the backbeat. Do your best and forget the rest, da doo ron ron ron da doo ron ron. Praise the Lord and pass the ammunition, hang by your thumbs and write when you get work, whoopitiyiyo git along little cowboys—and I am an American, I don’t eat my cheeseburger in a croissant, don’t look for a church that serves a French wine and a sourdough wafer for Communion, don’t use words like dodgy, bonkers, knackered, or chuffed. When my team scores, I don’t shout, Très bien!! I don’t indulge in dread and dismay. Yes, I can make a list of evils and perils and injustices in the world, but I believe in a positive attitude and I know that one can do only so much and one should do that much and do it cheerfully. Dread is communicable: healthy rats fed fecal matter from depressed humans demonstrated depressive behavior, including anhedonia and anxiety—crap is bad for the brain. Nothing good comes from this. Despair is surrender. Put your shoulder to the wheel. And wash your hands.

We live in an Age of Gloom, or so I read, and some people blame electronics, but I love my cellphone and laptop, and others blame the decline of Protestantism, but I grew up fundamentalist so I don’t, and others blame bad food. Too much grease and when there’s a potluck supper, busy people tend to stop at Walmart or a SuperAmerica station and pick up a potato salad that was manufactured a month ago and shipped in tanker trucks and it’s depressing compared to Grandma’s, which she devoted an hour to making fresh from chopped celery, chives, green onions, homemade mayonnaise, mustard, dill, and paprika. You ate it and knew that Grandma cared about you. The great potato salad creators are passing from the scene, replaced by numbskulls so busy online they’re willing to bring garbage to the communal table.

I take no position on that, since I like a Big Mac as well as anybody and I’ve bought food in plastic containers from refrigerated units at gas stations and never looked at the expiration date. And I am a cheerful man.

I rise early, make coffee, look out at the rooftops and I feel lucky. Today is my day. Other people, God bless them, go see their therapist. I never did. What would we talk about? I enjoy my work, I love my wife, my heart got repaired years ago so I didn’t die at 59 when I was supposed to. My dream life is mostly very chipper, sociable, sometimes I’m hauling crates of fish along a wharf in the Orkney Islands, one Orker bursts into song and we all sing together, me singing bass in a language I don’t understand, and I’m rather contented in my sleep. Why should I argue with gifts? A therapist would turn this inside out and make it a form of denial. It isn’t. I’d tell her the joke about the man walking by the insane asylum, hearing the lunatics yelling, “Twenty-one! Twenty-one!” and he puts his eye to a hole in the fence to see what’s going on and they poke him in the eye and yell, “Twenty-two! Twenty-two!” and she’d find a hidden meaning in it but there isn’t one, just a sharp stick. I’m not going to talk about my father because he’s dead and one does not speak ill of the dead, they are waiting for us and we will join them soon enough, meanwhile I feel good and thank you very much for asking. Sometimes, in church, when peace, like a river, attendeth my way, I feel actually joyful, I truly do.

I used to be cool and ironic and monosyllabic and now I’m a garrulous old man who’s about to lecture you about the importance of good manners (YAWN) and cheerfulness especially in grim situations such as 6 a.m. on a dark February morning standing in an endless line waiting to go through airport security and a TSA sniffer dog is walking along the line giving it a prison-camp feel and sleepy people toting baggage are waiting and the old man recalls pre-terrorist days when you walked straight to your gate, no questions asked, and he feels—well—sort of abused. And then a teenage girl walks past the checker’s booth to the end of the conveyor belt to put her stuff in the plastic bins and her lurching gait indicates some sort of brain injury. She seems to be alone. She also seems quite proud of managing in this situation, emptying her pockets, adopting the correct stance in the scanner, stepping out to be patted down by a TSA lady who then puts an arm around her and says something and the girl grins.

It’s a beautiful little moment of kindness. The cheerfulness of this kid making her way in the world. It reminds me of my friend Earl, who is 80 like me, who visits his wife every day at her care center and takes her for a walk, which cheers her up despite her dementia; he keeps in touch with his daughter who struggles with diabetes and an alcoholic husband; Earl is an old Democrat who is critical of the cluelessness of the progressive left when it comes to managing city government and law enforcement; but despite all this, he is very good company on the phone, never complains, savors the goodness of life.

I talked to Earl the night before the 6 a.m. line at Security and I think of him as I watch the girl collecting her stuff at the end of the conveyor. She feels good about herself and this strikes me as heroic.

So when I hear a woman behind me say, “This is the last time I fly early in the morning. This is just unbearable” (except she put another word ahead of “unbearable”), I turned and said, “Did you hear about the guy who was afraid of bears in the woods.” She shook her head. “His friend told him that if a bear chases you, just run fast, and if the bear gets close, just reach back and grab a handful and throw it at him. The guy says, “A handful of what?” “Oh, don’t worry, it’ll be there. It’ll be there.”

“Oh for God’s sake,” she said, and then she laughed. She said, “I can’t believe you told me that joke.” I said that I couldn’t believe it either. She said she was going to Milwaukee to see her brother and she intended to tell him that joke. So we got into a little conversation about Milwaukee. She said, “Have a nice day,” and I said, “I’m having it.”

It was not always sunshine and roses with me. I grew up in a small fundamentalist cult where the singing sounded like a fishing village mourning for the sailors lost in the storm. I spent years in a sad marriage eating meals in silence and wrote stricken verse and long anguished letters, had a couple brain seizures that made me contemplate becoming a vegetable, perhaps a potato, but recovered and finally realized that anguish is for younger people and now was the time to pull up my socks, so one day, having exhausted the possibilities of tobacco after twenty years, I quit a three-pack-a-day chain-smoking habit simply by not smoking (duh)—a simple course correction, the lady in the dashboard saying, “When possible, make a legal U-turn,” and I did and that turned me into a certified optimist. Smoking was an affectation turned addictive. I stopped it. A powerful deadly habit thrown overboard. I thought, “You have a good life and be grateful for it and no more mewling and sniveling.” I have mostly stuck to that rule.

Life is good. Coffee has taken great strides forward. There are more fragrances of soap than ever before. Rosemary, basil, tarragon, coriander: formerly on your spice shelf, now in the shower stall. I bought pumpkinseed/flax granola recently, something I never knew existed. Can rhubarb/radish/garbanzo granola be far behind? The slots in your toaster are wider to accommodate thick slices of baguette. Music has become a disposable commodity like toilet paper: the 45 and the CD are gone, replaced by streaming, which requires no investment. Your phone used to be on a short leash and the whole family could hear your conversation and now you can walk away from home and exchange intimate confidences if you have any. The phone is my friend. I press the Map app and a blinking blue dot shows me where I am, and I can type “mailbox” into the Search bar and it shows me where the corner mailbox is, 200 feet away. I already knew that but it’s good to have it confirmed. The language has expanded: LOL, FOMO, emo, genome, OMG, gender identity, selfie, virtual reality, sus, fam, tweet, top loading, canceled, indigeneity, witchu, wonk, woke, damfino. I come from the era of Larry and Gary and now you have boys named Aidan and Liam, Conor, Cathal, Dylan, Minnesota kids enjoying the luxury of being Celtic. Girls with the names of goddesses and divas, Arabella, Aurora, Artemis, Ophelia, Anastasia. We have the Dairy Queen Butterfinger Blizzard if you live near a Dairy Queen. Unscrewable bottle caps—no need to search for a bottle opener (once known as the “church key,” and no more). Shampoo and conditioner combined in one container. The list goes on and on. We have Alexa who when I say “Alexa, play the Rolling Stones’ ‘Brown Sugar,’” she does it. I can get the Stones on YouTube but then I have to watch a commercial for a retirement home, a laxative, and Viagra. And the tremendous variety of coffee cups! We used to get coffee cups as premiums at the gas station, all the same pastel yellow or green, and now we have cups with humorous sayings on them, Monet landscapes, the insignia of your college, an Emily Dickinson poem, you choose a cup that expresses your true distinctive self. We didn’t used to be so distinct.

I am no role model, my children. I have the face of a gravedigger, I get less exercise than a house cat, my water intake is less than that of a lizard, I am a small island of competence in an ocean of ignorance, I have three ex-girlfriends who wouldn’t be good character references, and yet I feel darned good, thanks to excellent medical care. I avoided doctors with WASPy names like Postlethwaite or Dimbleby-Pritchett and ones whose secretary put me on Hold and I had to listen to several minutes of flute music. I chose women doctors, knowing that women have to be smarter to get ahead in medicine. And what Jane tells me is that your most crucial health decision is the choice of your parents and I chose two who believed in longevity so I am a cheerful man and walk on the sunny side and meet the world’s indifference with a light heart. I put my bare feet on the wood floor at 6 a.m., pull my pants on, left leg first, then the right, not holding onto anything though I’m 80 and a little off-balance and if my right foot gets snagged on fabric it’s suddenly like mounting a bucking horse, but I buckle my belt and go forth to live my life. I’m a Minnesotan and have my head on straight so I get to the work I was put here to do. Some lucky nights I am awakened at 3 or 4 by a bright idea and I slip out of bed and put it on paper. When COVID came along, I accepted it as a gift and we isolated ourselves in an apartment on the Upper West Side of Manhattan like Aida locked in a tomb with her lover, Radamès, but with grocery deliveries, and Lulu our housekeeper came on Tuesdays.

A pandemic is a rare opportunity for a writer: I sat in a quiet room, nowhere to go, nothing to do, and I spun two novels, a memoir, and a weekly column. Most of the gifted artists I knew—musicians, actors, comedians—were out of work, whereas I, the writer of homely tropes and truisms, was busier than ever. The audience for a white male author is smaller than the state of Rhode Island but my writing is improving and I’m happy about that. My aunt Eleanor said, “We are all islands in the sea of life and seldom do our peripheries touch,” which surely was true during the pandemic but my island and Jenny’s often brushed peripheries and that was highly pleasurable and then of course there is the telephone.

I accept that I’m a white male though I don’t consider it definitive any more than shoe size is. I’m of Scots-Yorkshire ancestry, people bred to endure cold precipitation. Give us a whole day of hard rain and we feel at home. We are comfortable with silence and when we do speak, we utter short sentences rather than gusts. We aren’t prone to weeping though I sometimes do in church when it strikes me that God loves me. And when the woman I love sits on my lap, her head against mine, and says, “I need you,” I am moved, deeply. I don’t hurl brushfuls of paint at a canvas or compose a crashing sonata or write a long poem, unpunctuated, all lowercase, but I am moved. I knew I needed her but you can’t assume it’s mutual, so hearing it cheers me up. I don’t question her about the specific needs I satisfy, abstract theory is good enough.

Ralph Waldo Emerson, the Sage of Concord, the Champion of Cheerfulness, wrote back in the days of slavery when the beloved country was breaking in two:

Finish every day and be done with it. You have done what you could; some blunders and absurdities no doubt crept in; forget them as soon as you can. Tomorrow is a new day; you shall begin it well and serenely, and with too high a spirit to be cumbered with your old nonsense. Nothing great is achieved without enthusiasm.

For this and much more that he said, Emerson is the true father of his country, not the guy with the powdered hair and the teeth made of ivory and whatnot. All he said was “I cannot tell a lie” and that is simply not true. He was lucky in war, kept his mouth shut because of his bad teeth, and served as president before there was investigative journalism. I’d say he was the great-uncle of his country, maybe the stepfather. When I saw his picture next to Lincoln’s on our classroom wall, I thought he was Lincoln’s wife and not all that attractive.

When my daughter was 18, I went to prom at her school and stood in the gym with other parents as our kids processed in, boys in suits and ties, girls in prom dresses, the beams overhead and the tile walls all gay and glittery with banners and baubles, and a local rock band of codgers my age struck up “Brown-Eyed Girl” and our kids went wild, laughing and a-running, skipping and a-jumping, just like the song says, and we parents sang, “You, my brown-eyed girl, do you remember when we used to sing, Sha la la la la la la la la la lah de dah.” And then “So Fine” (My baby’s so doggone fine, she sends those chills up and down my spine). Old men with historic Stratocasters playing for our kids songs from my long-ago youth, the lead guitarist almost bald but with a slender gray ponytail like a clothesline coming out of the back of his head, playing his four or five good licks with great delight, and then My heart went boom when I crossed the room and I held her hand in mine.

This was a school for kids we once called “handicapped,” now we say “learning challenged” or “on the spectrum” but when the music played they were all equal in the eyes of the Lord. I went to public school: you stood on the corner, you boarded the bus, it took you to school. This school is one that each of us parents searched desperately for as our child sank into the academic slough. Many of the kids in the gym look as ordinary as you or me, and others are a little off-balance, quirky movements of head or arms, a speech abnormality. My heart clutches to see them dancing and I remember how shitty we were to kids like them when I was their age, it was so uncool to be seen with them and they never went to school dances, and here they were, ecstatic, including a girl injured as an infant who’s blind in one eye, walks with a lurch, one arm semi-paralyzed, and she was dancing like mad, and it struck me that jumping around on the dance floor these kids don’t feel there’s anything wrong with them. They are completely transported. Van Morrison didn’t write “Brown-Eyed Girl” as a therapeutic exercise, but here they are, dancing with abandon, and Grandpa Guitar is happy too, the wild boogying of oddballs a vision of paradise, and when the slow Father-Daughter dance struck up, I took my girl in my arms and I sang it to her, I feel happy inside, it’s such a feeling that my love I can’t hide, Oooooo.

That’s my vision of cheerfulness. You get some hard knocks in life but you still dance and let your heart sing. I didn’t get knocked as hard as those kids did and any despair I feel is simply grandiosity: get over it.

My girl is a hugger and snuggler like her mother and when I put my arms around her I feel I’m hugging my aunts, who are all gone, and my mother, though she was a shoulder-patter like me. I never hugged my dad except as a small child. When my girl was three, I took her to visit my dad who lay dying in the house I grew up in, the house he built in a cornfield in Minnesota in 1947, and he was delighted to see her. He moved a foot under the blanket and she reached for it and he moved it away and she grabbed for it and it got away again. She laughed, playing this little game. She was my best gift to him, his last grandchild. He was 88, I was 55. My father who’d been through miserable procedures in ERs and said, “No more” and was waiting to die and he was pleased as could be by the laughter of a little girl. She was delighted by him. And now I’m delighted to see her dancing to the grandpa band at the prom in the gym. God is good and His lovingkindness endures for generations.

I come from cheerful people. John and Grace kept a good humor and loved each other dearly. When Dad went into a luncheonette he always made small talk with the waitress: Looks like we’re finally getting spring. We can use the rain, that’s for sure. Boy, that apple pie sure looks good. You wouldn’t happen to have some cheese with that, would you? Apple pie without the cheese is like a hug without the squeeze. The little chirps and murmurs, the sweet drizzle of small talk. He spoke it well. Mother adored comedians, Jack Benny, George Gobel, Lucille Ball. My parents courted during the Depression, married in ’37, went through the War, built a house in the country, had six kids whom Dad worked two jobs to support while Mother cooked and cleaned and slaved in the kitchen every August, canning fruit and vegetables from a half-acre garden, the pressure cooker steaming, her hair damp with sweat, and I cannot remember them ever complaining about the unfairness of life or envying the privileged who bought their produce at SuperValu. Sometimes she said Darn it or Oh, for crying out loud.

Mother did not encourage complaint—“Other people have it worse than you,” she said, referring to children in China. She also said, “If you don’t have something nice to say, don’t say anything at all.” Which eliminated journalism as a career.

She admired FDR and Eleanor because they cared about the poor. My dad felt that the WPA was relief for the lazy, We Poke Along. Their difference of opinion never got in the way of their love for each other. Sometimes I’d find her sitting in his lap, the parents of six kissing. He was a little sheepish, she was not. Once I found a sex manual titled Light On Dark Corners in their bedroom and though it was dense with euphemisms, I understood that my parents lay naked in bed and did stuff, and I hoped to emulate this someday, whatever it exactly was.

I feel good in the morning, especially since I quit drinking in 2002. (The way to do it is to do it.) I have a clear head and I light a low flame under the skillet and think of the chicken as I crack the two eggs but when I fry the sausage, I don’t think of the pig. The egg is a work of art; the sausage is a product. As a young man I wanted to make art but I didn’t want to work in the academic factory to support my art, so I chose to do radio, which is a form of sausage. I admire the egg but I enjoy the sausage more. And it makes me feel cheerful, a good thing at the start of day before mistakes accumulate. My life is a series of mistakes. It’s cold in Minnesota so I went into radio because it’s indoors and vacuum tubes gave off heart. I set out to write humorous fiction à la Thurber and Benchley and S.J. Perelman did who were like the uncles I wished I had. I didn’t write serious fiction because that’s what I’d been forced to read by teachers and it had a penal quality about it. I made these big decisions based on no information and they turned out well. I’ve enjoyed lavish freedom to do homespun narratives sponsored by Powdermilk Biscuits and the American Duct Tape Council and talk about the poet Sylvia Plath who was full of sorrow and wrath and the day that she dove headfirst in the stove, she should’ve just had a warm bath—and if it was a modest enterprise, well, it was my own choice.

I have a dark side. I do not believe in regular exercise; I believe that an exemplary healthful lifestyle makes it more likely I’d be struck by a marble plinth falling off a facade as I walk to the health club. I can’t define “plinth” but I know it would kill me. I am quite cheerful staying home and I get my exercise reaching for things on high shelves.

My Grandma Dora sang me to sleep with “Poor Babes in the Woods,” lost in a snowstorm: “they sobbed and they sighed and they bitterly cried, and the poor little things, they lay down and died”—not a song Mister Rogers ever sang. Grandma did not tell us to look the other way when she chopped the head off a chicken. Death was a part of our lives. Not many children today have observed a beloved relative swinging an axe and a headless chicken flapping around on the bloody ground. I have. You must be aware of death to fully appreciate the goodness of life.

I learned cheerfulness from my folks. They had known hard times and now having a home, a garden, a car, gave them pleasure, and they savored it. I grew up in the Fifties, when my shyness led some of my aunts and teachers to imagine I was gifted. Actually I was autistic, not artistic, but autism hadn’t been invented yet, so I had the advantage of ignorance and by the time I learned what the problem was, it was too late for remedial ed, I was in my forties, a published writer with a popular radio show.

I was born with a congenital mitral valve defect that killed off two of my uncles in their late fifties. They simply dropped dead. Had I been born thirty years earlier, I’d be dead too. The defect kept me off the football team, spared me from brain injury, and the hometown paper hired me, at age 14, to write sports and I did my best to make a mediocre team valiant in print, thus my disability opened the door to a career in fiction.

I was lucky to live in Minnesota, a state proud of its numerous colleges and its homebred writers like Sinclair Lewis and Scott Fitzgerald, proud of its work ethic and Lutheran modesty and the call to public service and not so keen about euphoria so there was no reliable criminal element to supply dope, everything we obtained in college was substandard and diluted, the hashish was full of mulch, the cocaine was half talcum powder, the cannabis smelled of Maxwell House, the mushrooms were no more hallucinogenic than Campbell’s soup, so I didn’t experience euphoria until I was 45 and had two wisdom teeth extracted and was sedated and given painkillers, a dreamy experience. If I’d experienced it when I was 21, it could’ve sent me spinning into thirty years of rehab. But at 45 you know enough to know that real life is preferable to having a headful of golden mist.

In my twenties, I considered the idea of dying young and becoming immortal like James Dean in his sports car crash or Buddy Holly in the little plane in the snowstorm or Dylan Thomas drowning in drink, dying on their way up in the world, no sad decline into middle-aged mediocrity. Maybe this morbid thought came from my Scots heritage. Bluegrass comes from Scottish balladry, songs about dying bridegrooms and the bride taking poison at the burial and throwing herself into his grave. That sort of song.

Scotland is where golf comes from, a game that shows us the worst aspects of ourselves, potato-faced men in yellow pants riding electric carts in search of a white ball in tall grass and whacking it into a body of water and cursing God’s creation and then sitting in a clubhouse and getting soused on mint juleps and complaining about the income tax.

Thank God, I realized that immortality is no substitute for life itself. I missed an opportunity at early death in 1962 when, on a straight stretch in Isanti County on a two-lane highway, I got my ’56 Ford up to 100 mph and a pickup truck suddenly eased out of a driveway up ahead and onto the highway. In a split second, I swerved to go behind him and it was a good choice—he didn’t see me and try to back up—otherwise he and I would’ve been forever joined in a headline. Anyway I’d done nothing worth immortalization, just introspective stuff—“He looked out the window and saw the reflection of his own pale face against the drifted snow. She was gone. Like everyone else.”—A few years later I almost died young again when I bought a king-size mattress from a furniture warehouse and tied it to the roof of my car with a piece of twine and it blew off as I drove home on the freeway and I pulled over and ran back to rescue it and a big rig blew past me blasting his horn. A memorable thing, the Doppler effect of a semi horn doing 70 a few feet away. In 1983 my brother Philip and I canoed into a deep cavern in Devil’s Island on Lake Superior, attracted by the dancing reflections on the cavern ceiling and paddled way in until we couldn’t go farther and then paddled out, just as the wake of an ore boat a mile away came crashing into the cavern, waves that would have smashed us to a pulp and instead we sat in the canoe and watched the waves pounding into the cavern and said nothing, there being nothing to say. And eventually I turned 50, which is too old to die young. Whenever I relive those close-call moments, all regrets vanish, all complaints evaporate. I survived to do hundreds of shows and when the audience laughs it feels like a good reason to go on living.

And I’ve come to relish writing more and more especially after the Delete key was invented, which ranks with Gutenberg’s movable type in the annals of human progress. Back in the typewriter age we had liquid white-out but Delete enables you to remove whole pages of your own gloomy nonsense. I gave up dark writing for the simple reason that it fails to hold the interest of the writer. It’s boring.

Gloom is just like carbuncles:

Yours is the same as your uncle’s

Whereas the hilarious

Is wildly various

Like the wildlife found in the jungles.

I left Minnesota and friends and family in 2018 after Minnesota Public Radio, fearful of a shakedown scheme by two former employees, threw me out in the street, a miserable mistake on their part, and at 76, I needed to put it behind me and so we took up residence in Manhattan where I enjoy anonymity and Jenny loves the city and our daughter is nearby, so it was a smart move all around.

And when I stood in that gym watching her and my fellow autists leaping and dancing to the hits of my youth played by a man with a rope coming out of his head, it was so happy it made me cry just as I do in church when we sing about the awesome wonder of the world and the stars and the thunder O Lord, how great thou art and we old angsty Anglicans stand and raise our hands in the air at this Baptist revival hymn, we the overachievers transformed into storefront charismatics. It’s quite a sight. It happened one morning with the chorus, And I will raise you up, and I will raise you up, and I will raise you up on the last day.

It was Easter morning, brass players up in the choir loft, ladies with big hats, and when the clergy processed up the aisle, the woman swinging the censer looked like a drum major leading the team to victory over death. Resurrection is not something we Christians talk about in the same way we talk about our plans for retirement, but it’s right there in the Nicene Creed and in Luke’s gospel the women come to the tomb and find the stone rolled away and the mysterious strangers say, “Why seek ye the living among the dead?” This all hit me when we sang, “And I will raise them up,” I raised my right hand and imagined my long-gone parents and brother and grandson and aunts and uncles coming into radiant glory, and I was surprised by faith and I wept. My mouth went rubbery, I couldn’t sing the consonants. I stayed for the benediction, slipped out a side door onto Amsterdam Avenue, and headed home. Without the Resurrection, St. Michael’s’d be just an association of nice people with good taste in music but when it hits you what you’ve actually subscribed to, it can blow your head off, me the author standing and weeping among stockbrokers and journalists and lawyers for God’s sake.

This never happens at meetings of the American Academy of Arts & Letters up on 155th Street, writers and composers and painters and architects do not stand, singing, moved to tears: it simply does not happen. It happens at St. Michael’s on 100th Street. I don’t know if they do this at All Souls Unitarian over on the East Side, I think maybe they think about doing it, but hymns about inclusivity and tolerance and justice that leave Divinity out of it except as a beam of light or a rainbow or a starry sky—I’m sorry but that doesn’t make New York adults raise their arms and weep. The Lord is great indeed. He is here among us, from the public housing projects to the castles of Central Park West, amid the honking and double-parking of delivery trucks, God is here and we are His, we of the Academy and also kids on the spectrum, jumping and dancing. This cheerful thought can get you through some dark days. My mother knew deep grief when she was six years old, a little sister died of scarlet fever, and soon after, her mother died, and Grace lost the memory of her mother, couldn’t recall her voice, her manner, stared at snapshots of Marian trying to bring her to life, and it makes me happy to think of them reunited in happiness. There endeth my sermon. Go in peace.

This is a FREE NEWSLETTER. If you want to help support the cost of this newsletter, click this button. Currently there are no added benefits other than our THANKS! Any questions or comments, add below or email admin@garrisonkeillor.com