| -- | February 20, 2018 Blame IQ Tests for the Student Debt Problem By Patrick Watson Everyone is worried about debt. Government debt, household debt, personal debt, corporate debt. We are in it up to our eyeballs and often beyond. Debt is not always bad, though. The financial system can’t survive without it; banks and traders need debt to finance growth. As usual, the key is moderation. Debt can be good if it helps a person grow their business... or invest in a good education. Well, at least that’s the theory.

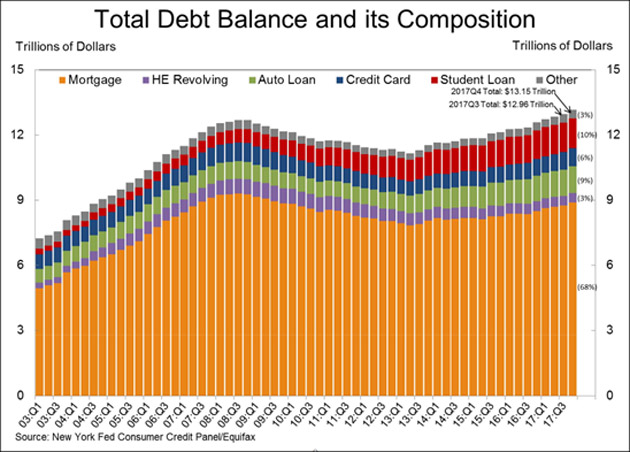

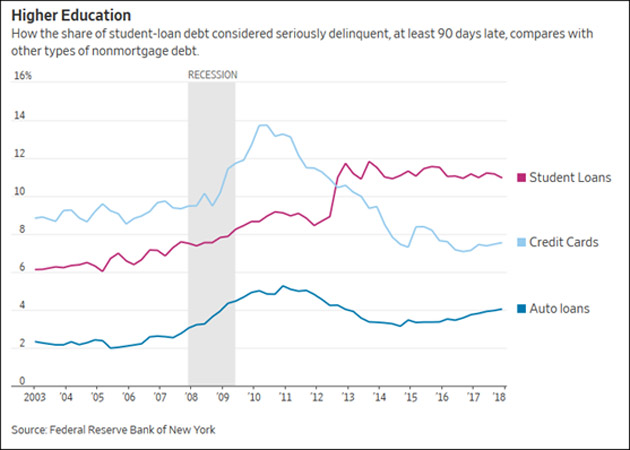

Photo: Getty Images Student debt should be productive—after all, it buys education that enhances your income. Yet for millions of Americans, that’s not what has happened, and the reason may surprise you. Before we get into the details, let me quickly suggest you invest (debt-free) in another kind of education: a Virtual Pass to next month’s Strategic Investment Conference. For the first time ever, the Virtual Pass will include video recordings of every presentation and panel from the SIC 2018. Even better, if you have some free time when the conference is happening, March 6-9, you can watch it live on your computer or mobile device. The Virtual Pass includes some other nice benefits too. It’s the next best thing to being with us in San Diego, so check it out here. Unpayable Debt The New York Federal Reserve Bank publishes an always-interesting Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit. The Q4 2017 version came out last week. Collectively, Americans carried $13.15 trillion in debt as of year-end 2017.  As you can see, most of it is mortgage debt—about 71% of the total if you include home equity loans (“HE Revolving” in the chart). Surprisingly, the next-largest category isn’t auto loans or credit cards. It’s student loans, which are now 10% of total debt. Their share has been growing steadily. This might be okay if the debt enhanced the student’s financial security, but often that’s not the case. Millions of borrowers don’t achieve the desired results but remain stuck with the debt anyway. Wall Street Journal‘s higher-education reporter Josh Mitchell had an interesting story on this last week. Using the same New York Fed data, WSJ showed this info on loan delinquencies:  While delinquency rates for other forms of debt fell after the recession, student loans didn’t. As of year-end 2017, about 11% of nearly $1.4 trillion in student debt was at least 90 days delinquent. It’s actually worse than that. Roughly half of student debt is held by borrowers who aren’t required to make payments yet because they are still in school, unemployed, or otherwise excused. Much of that debt would likely be delinquent too. Also important: the delinquent loans tend to be small (less than $10,000) and held by borrowers who never earned degrees. These borrowers probably thought they were doing the right thing. They wanted decent jobs and saw that having a college degree was necessary to get one. So why is college the key to gainful employment? It hasn’t always been so. It’s because employers require a degree as job qualification... and that’s partly the fault of IQ tests.

Photo: Getty Images Unreasonable Tests In 1971, the US Supreme Court decided a case called Griggs vs. Duke Power Co. The subject was employment requirements. Duke’s practice—and many other companies at the time—was to give job applicants an IQ test. Supposedly, this let them hire qualified people, but some companies also used tests to discriminate by race. The 1964 Civil Rights Act banned pre-employment tests that were not “a reasonable measure of job performance.” The court ruled that Duke’s tests were too broad and not directly related to the jobs performed, which made them illegal. Furthermore, the court said employers had the burden of proving employment tests were necessary for business purposes and not racially discriminatory. That’s hard to prove, so many US companies stopped using pre-employment tests at all. That left a problem, though. How were employers supposed to evaluate job applicants without illegally discriminating? | If you want to learn how to guide your portfolio through 2018 and beyond...  | You could learn a lot from an investor who manages $116 billion and has outperformed 92% of his peers over the past six years |  | Or a hedge fund manager who made hundreds of millions for his clients in the 2008 financial meltdown |  | And a bond manager who has correctly called the direction of the Treasury market for the past 37 years |

If you want first-hand insights and actionable ideas from these leading experts and 20 others, this is your opportunity! |

Soft Skills Employers really want to know two different things about prospective workers: - First, can this person perform the specific tasks that go with this job? That means operating a machine correctly, carrying boxes of a certain size and weight, writing computer code, etc. You might call these the “hard skills.”

- Second, there are soft skills. Is this person willing to stick with unpleasant assignments to the end? Will he show up on time? Can she work with others?

Those soft skills are harder to judge but critically important. They’re also what the Supreme Court made hard to test. College sort of requires those same soft skills. A degree may not give you much useful knowledge, but it shows you have some basic intelligence and literacy. It also shows you will jump through hoops if your organization tells you to. Employers value those qualities. The Griggs case said nothing about educational requirements. Employers remained free to require high school diplomas or college degrees… and the ruling gave them a big incentive to. College degrees are convenient, legal substitutes for the kind of testing employers haven’t been able to use since the 1970s. So apart from whatever you learn in college, merely having the credential became necessary to career success. As a result, everyone in the equation made certain choices. - Employers: demand a college degree even for jobs that don’t require college-level skills.

- Workers: get a college degree even if you must take on debt.

- Colleges: Raise prices since so many students were begging for degrees.

This made college more expensive, forcing students to borrow more and more money. Politicians jumped in to promote and guarantee those loans. And here we are. College Monopoly In the Griggs case, the US Supreme Court effectively granted colleges a monopoly. They can discriminate based on testing—or really a long series of tests that lead to a degree. Employers can’t. Like most monopolies, this one is inefficient. It creates unpayable debt that burdens students. Some of it eventually falls on taxpayers. Not ideal. Methods exist to evaluate prospective workers without requiring college degrees, and without racial or other illegal discrimination. But there’s no incentive to try them when you can just screen out the non-college graduates and accomplish the same thing. Resolving this impasse would help our debt problem and probably our employment problem as well. But the losers would be colleges and educational lenders, so don’t expect them to cooperate, unless someone forces them to. See you at the top,  Patrick Watson P.S. If you’re reading this because someone shared it with you, click here to get your own free Connecting the Dots subscription. You can also follow me on Twitter: @PatrickW.  | Subscribe to Connecting the Dots—and Get a Glimpse of the Future

We live in an era of rapid change… and only those who see and understand the shifting market, economic, and political trends can make wise investment decisions. Macroeconomic forecaster Patrick Watson spots the trends and spells what they mean every week in the free e-letter, Connecting the Dots. Subscribe now for his seasoned insight into the surprising forces driving global markets. |

Senior Economic Analyst Patrick Watson is a master in connecting the dots and finding out where budding trends are leading. Patrick is the editor of Mauldin Economics’ high-yield income letter, Yield Shark, and co-editor of the premium alert service, Macro Growth & Income Alert. You can also follow him on Twitter (@PatrickW) to see his commentary on current events. Senior Economic Analyst Patrick Watson is a master in connecting the dots and finding out where budding trends are leading. Patrick is the editor of Mauldin Economics’ high-yield income letter, Yield Shark, and co-editor of the premium alert service, Macro Growth & Income Alert. You can also follow him on Twitter (@PatrickW) to see his commentary on current events.

Share Your Thoughts on This Article

Use of this content, the Mauldin Economics website, and related sites and applications is provided under the Mauldin Economics Terms & Conditions of Use. Unauthorized Disclosure Prohibited The information provided in this publication is private, privileged, and confidential information, licensed for your sole individual use as a subscriber. Mauldin Economics reserves all rights to the content of this publication and related materials. Forwarding, copying, disseminating, or distributing this report in whole or in part, including substantial quotation of any portion the publication or any release of specific investment recommendations, is strictly prohibited.

Participation in such activity is grounds for immediate termination of all subscriptions of registered subscribers deemed to be involved at Mauldin Economics’ sole discretion, may violate the copyright laws of the United States, and may subject the violator to legal prosecution. Mauldin Economics reserves the right to monitor the use of this publication without disclosure by any electronic means it deems necessary and may change those means without notice at any time. If you have received this publication and are not the intended subscriber, please contact service@mauldineconomics.com. Disclaimers The Mauldin Economics website, Yield Shark, Thoughts from the Frontline, Patrick Cox’s Tech Digest, Outside the Box, Over My Shoulder, World Money Analyst, Street Freak, ETF 20/20, Just One Trade, Transformational Technology Alert, Rational Bear, The 10th Man, Connecting the Dots, This Week in Geopolitics, Stray Reflections, and Conversations are published by Mauldin Economics, LLC. Information contained in such publications is obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but its accuracy cannot be guaranteed. The information contained in such publications is not intended to constitute individual investment advice and is not designed to meet your personal financial situation. The opinions expressed in such publications are those of the publisher and are subject to change without notice. The information in such publications may become outdated and there is no obligation to update any such information. You are advised to discuss with your financial advisers your investment options and whether any investment is suitable for your specific needs prior to making any investments.

John Mauldin, Mauldin Economics, LLC and other entities in which he has an interest, employees, officers, family, and associates may from time to time have positions in the securities or commodities covered in these publications or web site. Corporate policies are in effect that attempt to avoid potential conflicts of interest and resolve conflicts of interest that do arise in a timely fashion.

Mauldin Economics, LLC reserves the right to cancel any subscription at any time, and if it does so it will promptly refund to the subscriber the amount of the subscription payment previously received relating to the remaining subscription period. Cancellation of a subscription may result from any unauthorized use or reproduction or rebroadcast of any Mauldin Economics publication or website, any infringement or misappropriation of Mauldin Economics, LLC’s proprietary rights, or any other reason determined in the sole discretion of Mauldin Economics, LLC. Affiliate Notice Mauldin Economics has affiliate agreements in place that may include fee sharing. If you have a website or newsletter and would like to be considered for inclusion in the Mauldin Economics affiliate program, please go to http://affiliates.ggcpublishing.com/. Likewise, from time to time Mauldin Economics may engage in affiliate programs offered by other companies, though corporate policy firmly dictates that such agreements will have no influence on any product or service recommendations, nor alter the pricing that would otherwise be available in absence of such an agreement. As always, it is important that you do your own due diligence before transacting any business with any firm, for any product or service. © Copyright 2018 Mauldin Economics | -- |