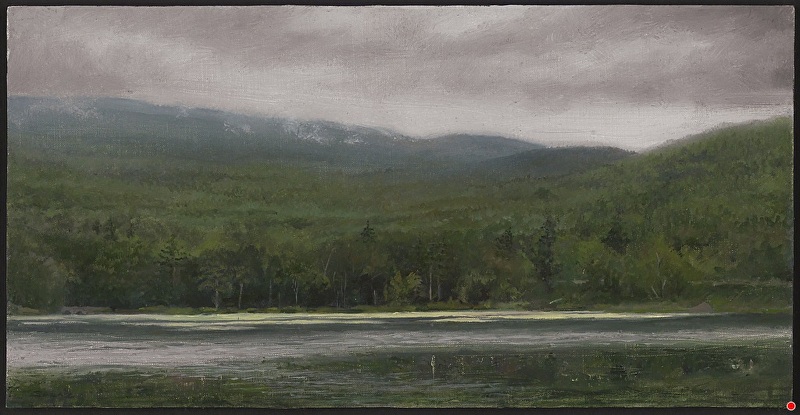

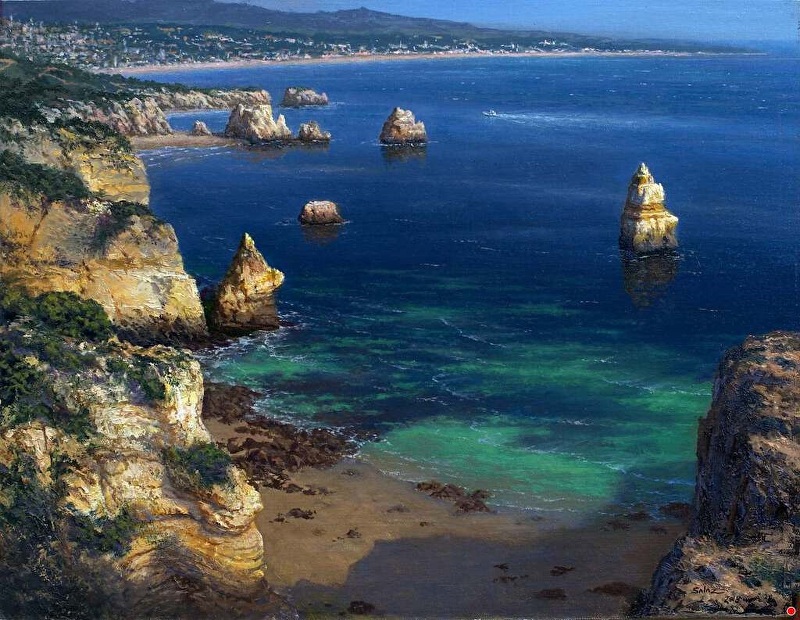

On the topic of the Hudson River School, I can see the influence of both the Tonalists and the Hudson River School in your painting style. They are two very distinct styles of painting, and I'm curious to know what in each style attracts you and how you synthesize them?

I think I'm influenced by the Tonalists by default, because I don't try to do any kind of Tonalist work but it just comes out. Back when I was in art school I loved George Inness; I had a book of his complete works and would look at it all the time, so I guess it made a deep impression. But to be more specific, this is an idea I discuss in-depth in my book, Landscapes in Oil, published in 2019. All the decisions on a painting are determined by the vision or the idea of the painting. I'm always painting from an idea or concept, like 'grace' or 'forgiveness', and when I'm painting these ideas guide my decisions. So, I don't try to paint either Tonalist or Hudson River School in style; the style of my painting is determined by whatever best captures the quality of the idea I'm trying to represent. And you can quote me on that. All the decisions on technique need to be determined by the vision of the painting. That way you're not distracted by isolated passages but keep the whole in view. I get philosophical really quickly when it comes to painting!

If the idea is the defining element in your work, do you begin the painting with the idea already in place or does the idea grow out of the work as it progresses?

The latter. It's an immediate response to nature. I'm not here to make pretty paintings or just copy nature. I'm having a response, a dialog with nature. This is where Emerson, Thoreau, and Whitman come in, because the Transcendentalists had the idea that everything in nature was the reflection of higher ideas. So rather than copying nature, I want to see nature and represent it as the crystallization of a universal idea. For example, I'm painting a plein-air study of a tree in a park near my home, and when you paint you get into these amazing states and the emotionality of light and nature is so amazing - it's transportive. I'm painting this tree and it's not just a tree in a park. It could be the tree that Newton's apple fell from. It could be the tree in the Garden of Eden. It could be the tree that Buddha sat under. The idea starts to expand. If you read Emerson, you'll see exactly what I'm talking about. On page 60 of my book, I have this quote by Emerson: "Every moment instructs, and every object; for wisdom is infused in every form." These guys were mystics.

Obviously you have many thinkers and writers who have inspired you. What inspired you to write a book?

There's three reasons why I wrote my book. One was that I had received a lot of training from Jacob Collins, and when I spent time with him painting in nature, I realized there was a whole tradition of landscape painting that was never going to be passed on, really. I mean, he still teaches and I teach and others teach, but there's no book that really explains these techniques. So I started writing this book on my own, for my students, and then I got a call from a publisher saying they loved my work and asking if I would be willing to write a book. Funny, I said, I just wrote one. And it's the book I wish I had had growing up.

The second reason was that I wanted to write a book on painting that was akin to The Art Spirit. Everyone who paints knows that book, and I wanted to write a book equally inspirational that was just for landscape painting.

And the third reason was that I feel I've found a way to break down the landscape in a way that is very clear and that I feel no one has ever done before, ever. I don't say that from bravado, but I took the lessons I learned and synthesized them and laid them out into a simple, clear method. I felt there's never been a book that simplified landscape painting into a simple, clear technique. In the book I break landscape itself down into three basic elements - just three. And then I break painting down into three basic elements. That's it, six things you have to deal with. Instead of floundering in the complexity of nature, you get this process to guide you.

Painting is hard to teach because it does have so many elements, and it's so helpful when they can be broken down into bite-size topics.

It is. For example, the three things on a painting: value, color, and drawing. All the mistakes on your painting are going to be one of those three. The three things on a landscape are the light, the atmosphere, and the objects. That's it. In the book I discuss how I break the landscape down, how Church did it, how Bierstadt did it, how Cole did it - they all did it in their own individual way. Having these six elements doesn't limit the creativity, it clarifies the creativity. For example, Charlie Parker Bird, one of the pioneers of Jazz and arguably the greatest alto saxophone player of all time, played a "A Night in Tunisia" in F major. He was infinitely creative with that key. So we can play within a key and have tons of creativity within that. One more thing about the book itself, you have drawing, value, and color. There are no books on value, by the way - ever think about that? - so there's this gaping hole on one-third of how to paint. But then there are also no good books on how to synthesize the three elements in a painting. So part of the reason I wanted to write this book was that I wanted to discuss how to combine these three elements in order to create not just a composition but a specific light effect, as well. Which is something else no one has ever gone into.

It sounds like your book covers in-depth the basics of painting in general, not just landscape painting. Are there any areas where a technique or concept might apply exclusively to landscape?

Yes, but it's a question of degree. When I paint the figure or still life, the objects are relatively constant and the light is fairly constant, and the atmosphere is completely constant. So landscape is actually the hardest of the subject matters because landscape is the only subject matter where all of the elements are changing. You can take these techniques and apply them to any subject matter - figure, still life, or if you're really gutsy, landscape!

For a beginner, do you recommend that they start with still life or figure before going into landscape, because there are fewer variables?

This is a big question of education because if you want to paint landscape well, you really have to study classically how to draw and control color and value, and that's usually best to learn with still lifes. But you also need to paint what you love; if you don't have the patience to sit and paint a cast, then find someone who can guide you in the classical tradition in regards to landscape. For example, another thing I discuss in my book is the seven aspects of drawing. What? There's only three elements in painting and seven in drawing? Those seven can be studied in landscapes and not just in still life. The seven aspects of drawing: shape, proportion, perspective, structure or anatomy, form, materiality, and character. Character isn't mentioned often but it's really the thing that determines all of the others.