The ECB is in a bind ahead of its Governing Council meeting this week. For one thing the economic and financial backdrop suggests that the ECB should maintain its policy stance. Then again it faces an unstable equilibrium it has itself contributed to: While financing conditions have remained favourable, a concerted action by Governing Council members over the past two weeks has prevented that bond yields rise too fast too much for the wrong reasons. Verbal intervention has bought the ECB time. It is unclear how much more time the ECB has left before markets test its resolve to put its money where its mouth is. To avoid an unwarranted tightening of financing conditions â in plain words: a market upset â the ECB needs to provide clearer guidance and explain its reaction function better this Thursday.

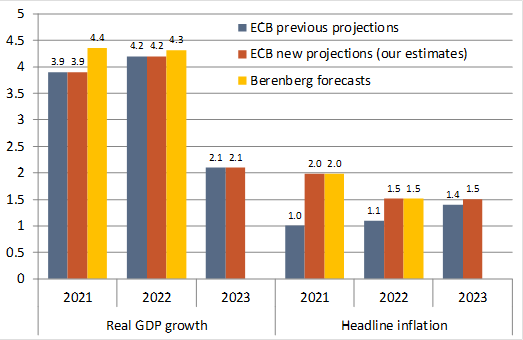

The medium-term outlook of the economy has not changed much relative to the ECBâs December staff macroeconomic projections. With respect to 2021, the likely downgrade to the GDP growth qoq forecasts for Q1 and Q2 2021 as restrictions remain in place for longer will largely be offset by the smaller-than-expected contraction in Q4 2020 and stronger growth estimates for H2 2021. Beyond 2021, prospects for growth above trend remain intact. Thus, we do not expect the ECB to change its 2021-2023 GDP calls (2021: 3.9%; 2022: 4.2%; 2023: 2.1% â see Chart 1) notably. The balance of risks is tilted to the downside near-term amid virus variants, but has probably remained stable since the last ECB meeting in late January. While the ECB will have to raise its near-term inflation projections up significantly â 2021 from 1% to possibly 2% and 2022 from 1.1% to 1.5% â as powerful one-offs boost the annual change in prices by much more than previously-expected, the outlook for underlying price pressures has not changed much. We expect the one-offs to start to fade in late 2021 and look for the ECB to emphasise this strongly in its communications on Thursday. Thus, the ECB may raise its 2023 inflation call only a little (from 1.4% to 1.5%) or even keep it stable.

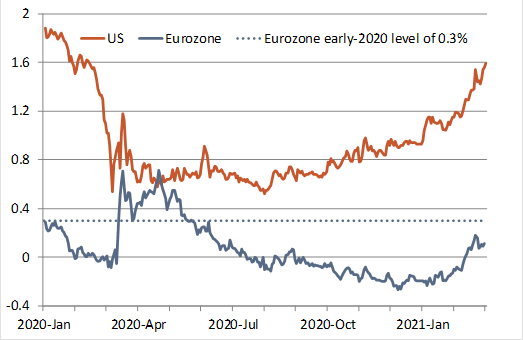

Both market- and bank-based indicators suggest that financing conditions remain favourable. Nominal 10-year GDP-weighted Eurozone sovereign bond yields at c0.1% remain at very low levels compared to historical levels and the 1.54% for US bonds (see Chart 2). Yields have risen by 30bps so far this year, but that is only half of the c60bp-gain in US yields. Most importantly, the rise in nominal yields owes exclusively to a higher inflation expectations. German 10-year real yields (yields on inflation-adjusted bonds) are even a little lower than at the turn of the year. Bond spreads have tightened significantly between Germany and Italy and remain resilient in the corporate world. Stock prices have risen while the euro has softened relative to a broad basket of other currencies. Bank lending rates remain low and credit provisioning healthy.

And yet, the ECB is under pressure to do more than simply maintain its policy stance and stress it is always ready to act. Otherwise it may risk coming across hawkish, or not dovish enough.

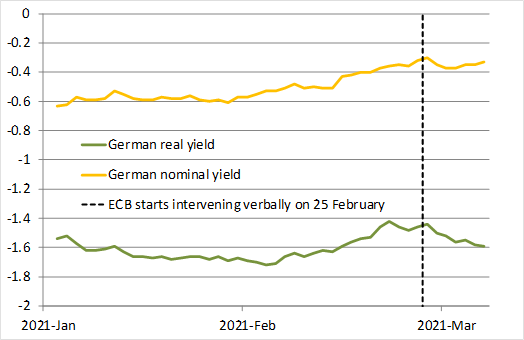

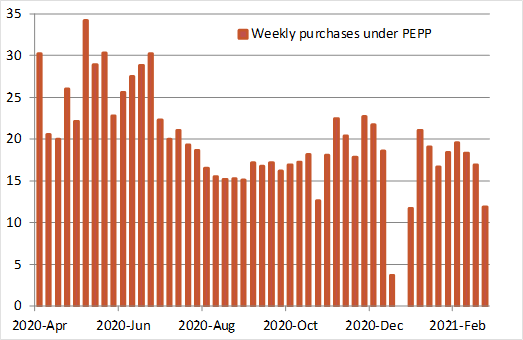

That financing conditions are favourable is an unstable equilibrium the ECB has helped establish. Until late February, 10-year Eurozone nominal bond yields had risen by 35bps. Thanks to a spill-over from US rates, real rates had even contributed 10bps to the rise in nominal yields. Acting on the earlier message that the ECB would avoid an unwarranted tightening of financing conditions, a number of Governing Council members stopped and reversed the trend in late February and the first days of March (see Chart 3). The verbal intervention that soothed bond markets for the past 10 days will unlikely work this week. At some point, action has to follow words. That the weekly pace of asset purchases under the ECBâs Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) has fallen for the fourth consecutive week to less than â¬12bn most recently is the wrong signal regardless of higher redemptions (see Chart 4).

If the ECB falls well short of expectations this week, financing conditions will tighten. While the US economy is in a position to deal with higher real yields, the Eurozone economy is in a different situation: the Eurozone economy entered the mega-recession with a bigger output gap, GDP dropped by more than twice in 2020, is facing a double-dip recession in early 2021, the vaccination roll-out is significantly slower so that restrictions will be in place for longer, and the â already or soon-to-be in the pipeline â fiscal stimulus is smaller. Thus it is less advanced in the recovery and will return to its pre-pandemic level probably a year after the US (in Q2 2020 vs. Q2 2021). Higher real yields would be an unwarranted tightening and could result in a much bigger upset than in the US last week when Fed Chair Jerome Powell âdisappointedâ markets.

So how to square the circle? Without giving up too much flexibility, the ECB should provide clearer forward guidance and explain better its reaction function. In other words, the ECB could be more transparent and specific about its contingency planning. We can think of three examples: 1) If real and nominal yields rise too fast too much for the wrong reasons, the ECB could accelerate its asset purchases under its flexible PEPP. 2) If credit provision stalls, especially if the Bank Lending Survey (next released on 20 April) shows credit standards tighten further and/or the Survey on the access to finance of enterprises (published on 1 June) points to lower credit demand, the ECB will make the conditions of its TLTROs even more generous. 3) If the euro re-strengthens significantly, currently a not so likely prospect, the ECB could revert to a deposit rate cut.

With respect to the more medium-term reaction function of the ECB, the likely debate that ECB Governing Council member Fabio Panetta has started with his âharder, better, faster, strongerâ comment is interesting. In one of probably the most dovish speeches in recent ECB history, Panetta stressed the disinflationary side-effect of running the Eurozone economy hot: pushing demand aggressively towards the economyâs potential may itself help boost that potential. The Fed had similar discussions before it switched its strategy to average inflation targeting. The ECB is concluding its strategy review this year. As the intuition of a somewhat reverse hysteresis effect is making inroads, it may feature more prominently in the discussions of the ECB.

As before, the ECB will make the point over and over again that fiscal policy remains in the driver seat. A bigger fiscal stimulus can contribute to higher business confidence, raise capital formation, boost employment, lift inflation (expectations), and, if central banks contain the rise in nominal yields, lower real rates can further support growth. At the same time, more income support can boost household spending, improve corporate balance sheets, limit loan losses for banks, keep credit standards and therefore financing conditions favourable, adding to growth again.

Chart 1: ECB vs. Berenberg projections (in %) |

|

Source: ECB, Berenberg |

Chart 2: Nominal 10-year sovereign bond yields â Eurozone vs. US (in %) |

|

Source: ECB, US Treasury, Berenberg |

Chart 3: Impact on ECB intervention on sovereign bond yields in 2021 (in %) |

|

Source: Bundesbank, Berenberg |

Chart 4: Weekly asset purchases under PEPP (in bn euros) |

|

Source: ECB, Berenberg |

Florian Hense

Senior European Economist

BERENBERG

Joh. Berenberg, Gossler & Co. KG

London Branch

60 Threadneedle Street

London EC2R 8HP

United Kingdom

Phone +44 20 3207 7859

Mobile +44 797 385 2381

E-Mail florian.hense@berenberg.com

Joh. Berenberg, Gossler & Co. KG is a Kommanditgesellschaft (a German form of limited partnership) established under the laws of the Federal Republic of Germany registered with the Commercial Register at the Local Court of the City of Hamburg under registration number HRA 42659 with its registered office at Neuer Jungfernstieg 20, 20354 Hamburg, Germany. A list of partners is available for inspection at our London Branch at 60 Threadneedle Street, London, EC2R 8HP, United Kingdom.

Joh. Berenberg, Gossler & Co. KG is authorised by the German Federal Financial Supervisory Authority (BaFin) and deemed authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. The nature and extent of consumer protections may differ from those for firms based in the UK. Details of the Temporary Permissions Regime, which allows EEA-based firms to operate in the UK for a limited period while seeking full authorisation, are available on the Financial Conduct Authorityâs website. For further information as well as specific information on Joh. Berenberg, Gossler & Co. KG, its head office and its foreign branches in the European Union please refer to http://www.berenberg.de/en/corporate-disclosures.html.