Monetary policy works the same way. Central bankers think they can handle a situation and fire the artillery. It always has an effect… but ultimately it is rarely the effect they wanted. Doing nothing at all might have been better but that wasn’t an option. They’re trapped in an endless spiral of intervention. Not because it’s the best policy, but because it’s what they have been taught.

We don’t need ancient history to discern this. Just go back to 2008. The Federal Reserve attacked a housing-driven recession and financial crisis by dropping rates to zero. When that didn’t work, they tried the massive bond purchases we now call “quantitative easing.” The economy stabilized, though it’s still not clear QE is what did the trick. I personally believe, both practically and philosophically, that the recovery was the result of a million entrepreneurs figuring out how to manage their own businesses in the midst of crisis.

But the resulting financial cease-fire—consisting of low growth and minimal inflation—didn’t end the conflict. Every attempt to reduce or remove the interventions set off more fireworks. Finally, COVID forced the Fed to double down. Powell and crew launched a 2008-style intervention on steroids. Like the last one, it restored stability but with major side effects, this time inflationary.

Now here we are, with a “soft landing” narrative increasingly making people believe the Fed saved us all. While I see much to celebrate (we will visit the positives below), I also see slowing growth, still-high inflation, Fed officials still aggressively intervening and little reason to think they have improved their skills.

I wish the Fed would declare victory and bow out. I doubt we’ll be that lucky.

I am widely known as the Muddle Through Guy. While we all rightly fear extreme scenarios, reality is usually in-between. That’s essentially my inflation outlook: We avoided the worst-case hyperinflation, but the pre-COVID disinflation is gone. It will stay generally in a higher 3-ish% range for the near future.

While the economy might adapt to that kind of inflation (we lived with it in the ’80s and ’90s, after all), Jerome Powell and other central bank leaders don’t seem inclined to accept it. They continue to target inflation levels (Core PCE at 2%, in the Fed’s case) that look unattainable unless they keep policy tighter for longer. This week Powell said he didn’t foresee reaching the goal this year or next.

That probably means we can expect tight policy until 2025 at least. That’s not necessarily wrong; controlling inflation has to be the top priority. But the necessary policies could make the inevitable recession deeper and possibly ignite a financial crisis. Finding the right balance will be hard if inflation remains higher than the Fed wants, as I expect.

Last week I described how housing prices will keep inflation elevated even if everything else falls back to the 2% target. But there’s another big factor we need to discuss: the labor shortage and wages. And their impact may not go the way you think.

I mentioned in the last letter a new report from my good friend Bill Dunkelberg, who is chief economist at the National Federation of Independent Business. NFIB does regular surveys of how its members view business conditions, so Bill has a good handle on “Main Street” economic sentiment. Right now, it’s strangely split.

Despite inflation and recession fears, the small business owners in NFIB’s sample show a lot of confidence—enough to keep hiring plans historically high. They want to expand and need more workers but can’t find enough. NFIB’s latest survey found 60% of small businesses were searching for workers and 43% said they had no qualified applicants.

The law of supply and demand says supply will appear if the price is right—wages, in this case. Businesses have raised wages and benefits to attract workers. But even that doesn’t always help. Like you can’t get blood from a turnip, you also can’t hire workers who don’t exist.

Now think about how this affects inflation. On the one hand, the higher wages needed to attract workers in this economy put more money in their pockets, which adds to consumer demand. That’s inflationary. But the inability to hire also keeps businesses from expanding. Lacking staff, they don’t open new stores, set up new assembly lines, and so on. This holds back GDP growth, which is ultimately disinflationary—though it may first add to inflation pressure by reducing supply.

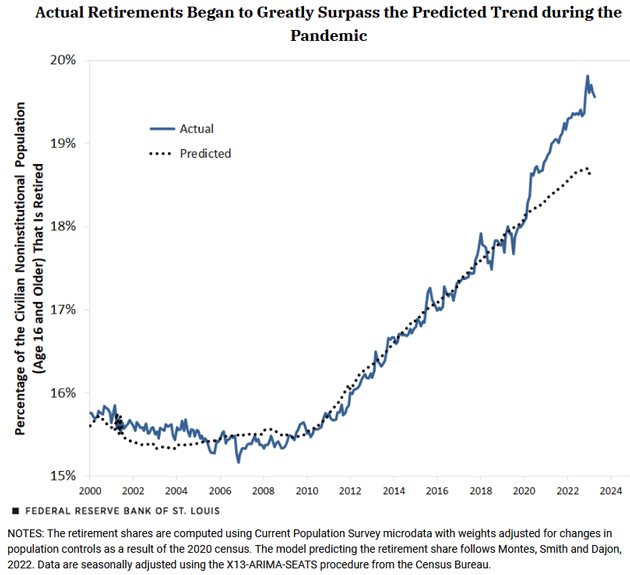

You might wonder why we lack workers. Economists have been debating this for a couple of years now. Several things contribute, but the single biggest factor seems to be early retirements. COVID inspired a cohort that was already nearing retirement age to leave the labor force earlier than planned.

Researchers at the St. Louis Fed recently tried to model the impact, considering the relative levels of pay for various demographic groups against their available Social Security benefits and other retirement income. They estimate the US has about 2.4 million “excess” retirees above the previously normal pace. If correct, that’s almost enough to explain the drop in participation rates.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

But it’s not simply a matter of retirees being unavailable to work. They also continue creating demand—for housing, food, energy, health care, and everything else. Those still working can only produce so much—pointing to yet more inflation.

The labor challenge doesn’t end there, though. It may only be getting started.

The labor shortage is hard to solve because it is mainly demographic. Birth rates fell after the large Baby Boom generation, which is now retiring. In the US we partially cushioned the impact with immigration. Others like Japan and Korea (and now China) didn’t, so their problems are even worse. But on a global scale, the only real solutions are technology that improves productivity. AI may help in a few years. Unfortunately, the problem is here now.

The Bank for International Settlements talks about this in its new Annual Economic Report, pointing to some possible inflationary consequences. Here’s a key point (my emphasis in bold).

“The surprising inflation surge has substantially eroded the purchasing power of wages. It would be unreasonable to expect that wage earners would not try to catch up, not least since labor markets remain very tight. In a number of countries, wage demands have been rising, indexation clauses have been gaining ground and signs of more forceful bargaining, including strikes, have emerged. If wages do catch up, the key question will be whether firms absorb the higher costs or pass them on. With firms having rediscovered pricing power, this second possibility should not be underestimated. Our illustrative simulations indicate that, in this scenario, inflation could remain uncomfortably high.”

Follow the sequence here (and note, this isn’t just in the US). Wages, while higher, have still lagged inflation in many (if not most) places. Workers are realizing they have leverage, and they are learning how to use it. Note that workers who go to new jobs get higher wage increases than those who stay. Many employers will have little choice but to raise pay levels.

Then what? Note the bold sentence. “Absorb the higher costs” is another way of saying “Accept lower profit margins.” That’s obviously not attractive for managers and shareholders; better to pass on the higher labor costs to customers via higher prices. And the “rediscovered pricing power” will let many do exactly that.

My friend Sam Rines of Corbu calls this “price over volume” or PoV. He has been illustrating this for at least six months from earnings calls from various companies who have grown revenues on lower volumes. They have maintained margins and earnings by raising prices. Managers are learning price helps the bottom line more than volume.

This is something we haven’t seen for a very long time. My generation clearly experienced it in the ’70s, ’80s, and somewhat into the ’90s, but in general we expect lower volume to mean lower prices in order to stimulate demand. We are in a strange place where demand is willing to pay extra. It is going to be difficult to look at past models and try to predict the future based upon them. Past performance is truly not indicative of future results.

This combination of higher wages and higher prices can produce the much-dreaded “wage-price spiral” (though BIS doesn’t use that term) which feeds on itself and is hard to stop. We haven’t seen it so far in this cycle. Indeed, real wages have actually declined in many industries. As BIS says, it’s unrealistic to expect this will continue indefinitely. People can only absorb so much pain, and seeing your living costs rise faster than your income is definitely painful.

BIS is the central bank of central banks. It doesn’t have a lot of formal authority, but its messages get attention. Now BIS seems to be telling policymakers around the world their work isn’t done, and inflation remains a real threat.

That’s probably correct, too. Firmness in housing prices and wages will spill over to everything else. That’s not to say inflation will return to last year’s peak… but it doesn’t have to. Remember, inflation is a rate, not a level. If annual inflation drops to 0% it simply means the prices that rose so high in the last year have stabilized at a higher level.

This has consequences. If central banks continue seeing inflation as a serious threat, looser monetary policy is unlikely in the major economies this year or next.

I think the next year or two will see inflation hold at some “muddle through” level—higher than we would like but not a crisis in itself. The crisis, if we get one, will be in the response to this inflation.

The Fed and others aren’t wrong to worry about inflation. They should do all they can to get it down to some minimal level. Any inflation at all is harmful, even their 2% target. I have been very clear on this point. But now all the options are bad. Looser policy in these conditions would please Wall Street but could also undo more than a year of hard-won progress. Tighter policy could do the opposite, aggravating a future recession that would otherwise have been minor.

And again, let’s note that simply keeping rates where they are counts as “tightening.” The passage of time lets the impact sink deeper into the economy. A lot of it is invisible because it manifests as activity that doesn’t happen. Building projects never get off the drawing board because financing costs make them unprofitable, for example. People don’t sell their homes and pursue new opportunities because they can’t afford another mortgage. All this adds up.

But the real risk is what we got a small taste of this spring when some regional banks failed. Those were manageable, but they revealed something important. There is a lot of unwise risk-taking out there, some of it by people from whom you would expect better. They assumed—correctly in these cases—they would be bailed out.

Even if you think bailouts are appropriate, the system simply isn’t capable of bailing out everyone. Will they try? I think so. “Do nothing” just isn’t in the Fed’s DNA, even if that’s the best response. They will intervene—again—because that’s what they always do.

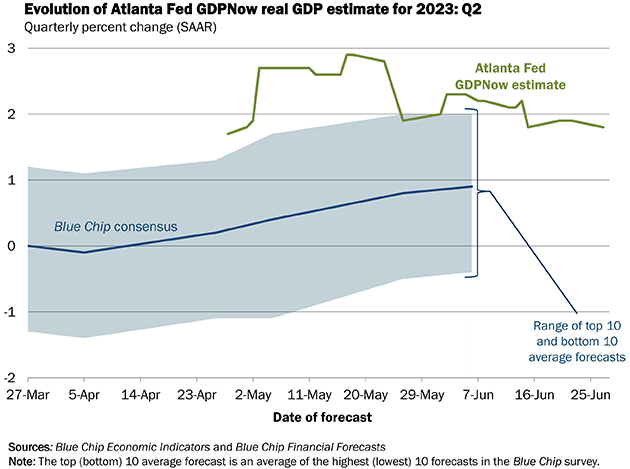

I keep using the word “recession” like it is some inevitable just-around-the-corner event. Obviously, that’s not the case, at least in the US. We just saw Q1 GDP revised up to 2%. Not a halcyon event, but not shabby either. There are actually a lot of good things happening.

Housing is a lot stronger than anybody would have thought it would be (well, other than Barry Habib and a few other housing prognosticators) with mortgage rates around 7%. Housing inventory is the lowest since 2012. And while prices are definitely softening in some areas, nationally they are still rising.

Let's look at a few other positive data points (h/t Michael Boyd).

Consumer confidence is at a 17-month high. The belief that we are heading into recession has dropped. For all that we keep talking about a recession, the markets are not that far off from their all-time highs. (Of course, that is aided and abetted by 10‒15 stocks reaching for the moon.)

Inflation is in fact falling—maybe not to 2%, but well below 8%. The trend is our friend.

Unemployment is close to all-time lows. There was a time in the very recent past when economists considered 4% unemployment to be full employment.

Consumer spending is up as much as it’s been this century.

2% GDP? 3.7% unemployment? Seriously? This hardly looks like recession.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta

At the next FOMC meeting, they will have had an advance look at the GDP number (which will be public the next day). They will have the latest CPI and PCE numbers. If they see 1% plus GDP growth, let alone the almost 2% that the Atlanta Fed model is forecasting, the question will not be whether they raise rates 25 basis points but if they go for a full 50. I don't think they will, but 50 basis points is now on my bingo card. That would be a strong statement about how serious they are about inflation.

On the flip side, the rest of the world is not doing well. China is sick. I, and a number of others, have been surprised by China’s weak recovery. Looking at the PMI manufacturing indexes (readings below 50 indicate contraction), the EU is at 43.6, the worst since October, and the fifth decline in a row. The UK is at 46 for a fourth consecutive decline. Germany is at 41, a fifth straight drop and the worst in 8 months. Japan has slipped into negative territory at 49.8.

With apologies to John Donne, no country is an island, as far as their economy is concerned. And the US will be affected by the rest of the global economy. A relatively solid, if less than we would hope for, GDP number combined with low unemployment will give the Fed permission to continue to raise rates.

Am I allowed to say this out loud? If the economy stays as strong as it currently looks and inflation stays above 3%, it is possible that the Fed could exceed its own 6% forecast. Go back to your dot plots of a year ago. Was the consensus 6% like it is now? No, it wasn't. Inflation hasn’t dropped as fast as they wanted. The economy has held up in spite of their rate increases. I suspect they will continue raising rates until something breaks.

Recession is the only tried and true inflation “fix.” Everybody gamely talks about “soft landing.” I think what they really mean is a mild recession that tames inflation.

Monetary policy aided and abetted inflation, but it was not the primary cause, in my humble opinion. The main cause was fiscal policy. Many would argue that the inflation we saw was better than a deep depression. We will never know the actual potential outcomes, as this was a one-time experiment, which cannot be repeated. Stay tuned…

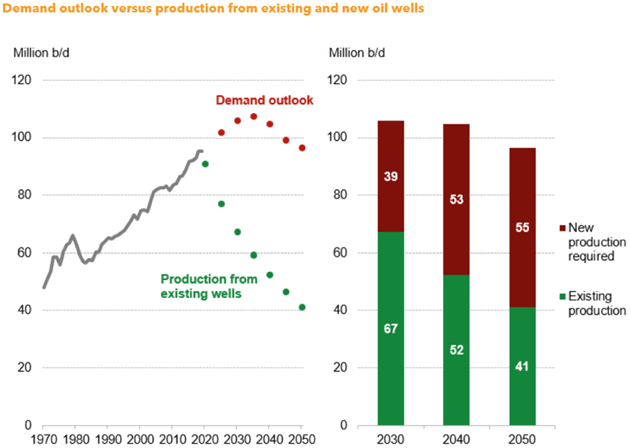

I have become increasingly convinced that the ESG movement, by trying to restrict investments in oil and gas ventures, is going to have the perverse effect of reducing supply even as global demand increases, thus making the price of energy rise. It is simply not rational for the developed world to expect developing countries to ignore the needs of their citizens to have access to power and clean water which requires energy, and specifically oil and gas (and to some extent coal).

Even as global growth is slowing, the price of energy is surprisingly remaining stable. When we get past this current growth recession, demand is going to pick up even as we are watching supply get tighter.

History clearly shows that the increased use of energy (of all types) is what drives the economics, health, and prosperity of humanity. The data on supply and demand for oil and gas is compelling. Once again, this year will be an all-time high in demand for oil and gas, a trend that has only been interrupted during recessions over the last century before quickly recovering to new all-time demand highs. I am bullish over the medium- and long-term prospects for oil and gas prices. The chart below shows that we are going to need to drill a lot of wells just to stay in place, let alone meet increased demand.

Source: Bloomberg

The question is: What is the best way to take advantage of this misguided policy?

Bottom line: One potentially significant upside in oil and gas investing is not just the actual price of oil and gas (which is important!), but the increase in the value of proven and probable reserves in a given oil and/or gas field. Think of it as buying an older apartment complex in a good neighborhood, doing a complete renovation, increasing the price of the rent, and then selling the complex at the new increased value. Essentially, what my partners at King Operating do is buy the rights to drill in an older but proven field in a “great neighborhood.” Typically, the older fields were all vertical wells, but you can improve the value of that old field by doing horizontal drilling and fracking. (Oil and gas is a risky business and past performance is not indicative of future results.) It's more complex than that, but that is the essence.

My partners at King Operating have helped pioneer this investment model (wells plus the field) for retail investors. I have written the first of what will be a series of research papers on energy, that also outline the strategy. I think it is some of the best research and writing I have done in years. I really hope you read it. Due to regulations, this offer is limited to accredited investors. If you would like your copy of my report, click on the link below at the end of the following disclosure.

Important disclosures: Note that John Mauldin’s association with King Operating is completely separate, legally and financially, from his involvement with Mauldin Economics. The opportunity presented above by John Mauldin in TFTF is not endorsed by Mauldin Economics, ME Research LLC, or any of its other partners nor do any of them have any financial or other interest in the described venture.

John Mauldin will be receiving significant financial benefits from investments made in this venture by investors. More specifically, as chief economist of King Operating, John is entitled to receive consulting fees as well as a significant interest in the fund’s general partner.

This opportunity is offered by King Operating and it is limited to accredited investors. Prospective investors should carefully review the offering memorandum and risks disclosure before proceeding.

Click here to download my report The Future of Energy on King Operating’s website and find out more.

As you read this, Shane and I are in Cancun for my son Henry's wedding. He asked me to be his best man. Is there anything cooler for a Dad? His fiancée and now wife Lauren wanted to marry on the beach.

I am really looking forward to once again returning to FreedomFest. Longtime friend Mark Skousen (40 years!) has put together his best conference ever, a celebration of libertarian philosophy and economics. I will see lots of old friends (looking forward to dinner with George Gilder [assisted by a local reader] and then a night at BB King’s) but there are some people I really want to meet who will also be there. I will be speaking/on a panel at least three times and you will be able to find me near the King Operating booth, doing live video podcasts and talking to you. You can see the lineup and if you decide to attend use the special code MIKEROWE77 to get a $77 discount. Mike is a featured speaker whom you may know as the host of “Dirty Jobs” and as an advocate for technical trade training. Presidential candidates, economists, and a lot of fun. Barbecue and blues. Look me and Shane up if you come.

We have a new video with my partner Ed D’Agostino interviewing our own Jared Dillian about his market outlook. Is now the time to be bullish? Read the transcript here and find out.

Have a great week and enjoy your summer! Unless of course you're in Australia. Or Texas where it is too hot. And don't forget to follow me on Twitter.

Your glad to see the economy as strong as it is analyst,