|

On Wednesday, Facebook and Twitter faced their first major test of the 2020 election. The New York Post published a story with illicitly obtained emails from Hunter Biden’s hard drive, obtained in the most sketchy of methods: Rudy Giuliani shared the material after a computer repairman gave it to his lawyer. Steve Bannon had tipped off the Post to its existence.

The story made questionable claims about Biden and his father based on improperly obtained documents, and the platforms took action. Facebook almost immediately decreased its distribution. Twitter blocked the link. And then conservatives went ballistic.

“The most powerful monopolies in American history tried to hijack American democracy by censoring the news & controlling the expression of Americans,” said Missouri Senator Josh Hawley, distilling the wave of criticism into a tweet.

Rather than a grand conspiracy against Republicans however, what’s happening inside these companies is simpler: They’re desperately trying to avoid being caught up in the type of post-election controversies they were in 2016, and are making it up as they go. With no consistent content moderation strategy, they're struggling to explain their decisions, opening themselves up to the type of criticism we’re seeing this week, and previewing what could be a disastrous Election Day, where a disputed result seems inevitable.

Fake news, hacked documents, and foreign disinformation dominated the post-2016 election discussion. These issues blew up, in part, as liberals and media types sought to explain Hillary Clinton’s loss. But for Facebook and Twitter, they were an undeniable problem. If you control a social platform, you don’t want disinformation spreading like wildfire, especially the election-related variety. Being a vector for it lands you in trouble with regulators, politicians, and the public, and then you spend your time explaining yourself instead of building new products. When you look up, TikTok is taking your users.

To solve for this after 2016, the social platforms reoriented themselves to make fast moderation decisions. You could see this in action when Facebook quickly banned posts that contradicted the World Health Organization’s guidance on the coronavirus. The speed was also evident when Facebook banned QAnon earlier this month after the conspiracy exploded during lockdown. Such moves would usually take years for the typically over-deliberative Facebook, but the company has set up new teams, including a special “Risk and Response” unit (who I met with in Always Day One), that help it act fast.

“They are trying to be more agile,” one person who’s engaged with the tech companies on these issues told me. “What that means though is that they will probably overachieve for some people's tastes and underachieve for others.”

When the Hunter Biden story went up on Wednesday, both companies acted fast. The story triggered 2016 alarms, with some of the old components — illicitly obtained information of dubious provenance — and Facebook and Twitter quickly reduced its distribution. But it was also a judgment call: A mainstream American newspaper wrote up the material, and the fact-checking could take a while. Without clearly defined principles outside of “don’t let a repeat of 2016 happen” the fast action turned into a mess.

Both platforms struggled to explain their decision. Facebook said it reduced the story’s distribution because it was sent for a fact check, which it said was standard practice for all such stories. But this explanation befuddled even its own fact-checking partners. “How long Facebook has been reducing distribution of a story before it’s fact-checked?” Baybars Örsek, director of the International Fact-Checking Network, asked aloud on Twitter. “The fog above those ad hoc decisions without clear insights and metrics are not helping the cause.”

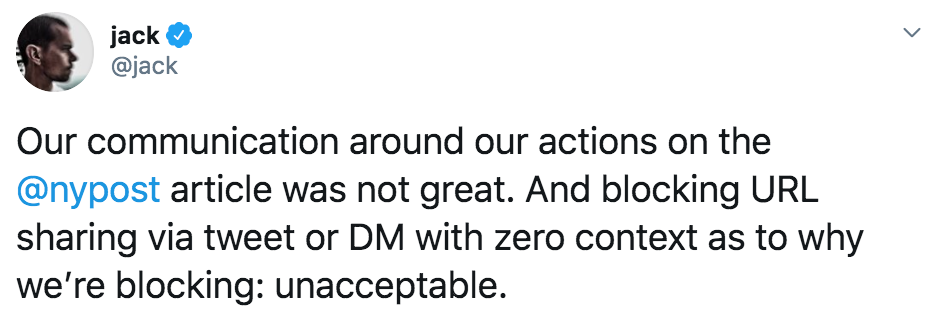

Twitter said it blocked the link to the Post story because it contained hacked material. But the company offered so little context that Jack Dorsey later apologized, calling Twitter’s communication unacceptable. Twitter later said the company prohibited “the use of our service to distribute content obtained without authorization” a bizarre statement that would cover much of investigative journalism as well.

The foggy explanations have helped conspiracies run wild, as politicians like Hawley, eager to play victim, are exploiting the void between good information and what’s actually playing out. The real worry is this happens again on election night, where more poorly articulated enforcement actions could add fuel to claims the election was rigged, leaving the platforms apologizing again.

Flying Through a Surge

|

I’m about to fly for the second time since the coronavirus outbreak began, heading back to San Francisco after a lovely few weeks on the East Coast (it was nice to experience fall for the first time in years). Flying during this pandemic is actually quite pleasant: Airports are empty, as are planes, boarding is fast, lines are nonexistent. It’s a joy as long as you’re okay with wearing a mask. But there’s always the worry you’ll catch a life-threatening virus, something I worry about as a third wave crests. Such is life in 2020 though. I’ll cross my fingers and hope for the best.

This Week On the Big Technology Podcast: New York Times’ Ben Smith Talks Slack, Newsroom Politics, and Tech Regulation

As the Media Equation columnist at the New York Times, Ben Smith is covering an industry going through transformation and turbulence. And as the former editor-in-chief of BuzzFeed News — a place I worked until this June — he lived that change while managing a newsroom of reporters who lived online in a VC funded media company.

In this week’s edition of the Big Technology Podcast, I caught up with Smith for a discussion focused on how tech is changing journalism, what media companies can do to connect with people that have shut them out, and where big tech regulation may lead.

You can check it out on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and Overcast, and read the transcript on OneZero.

Your thoughts?

I welcome your thoughts after each issue. Feel free to send tips and ideas by replying directly to this email (or use alex.kantrowitz@gmail.com) and they’ll come right to my inbox.