| View in browser |

|

| |

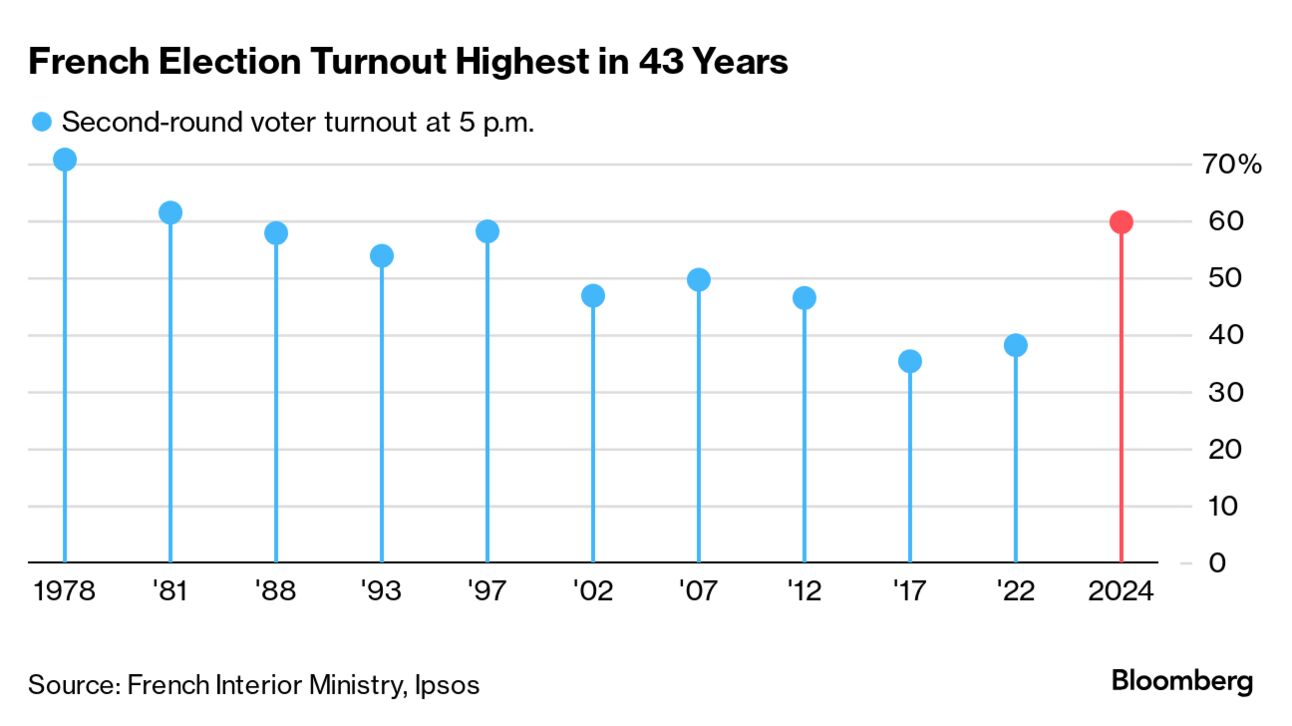

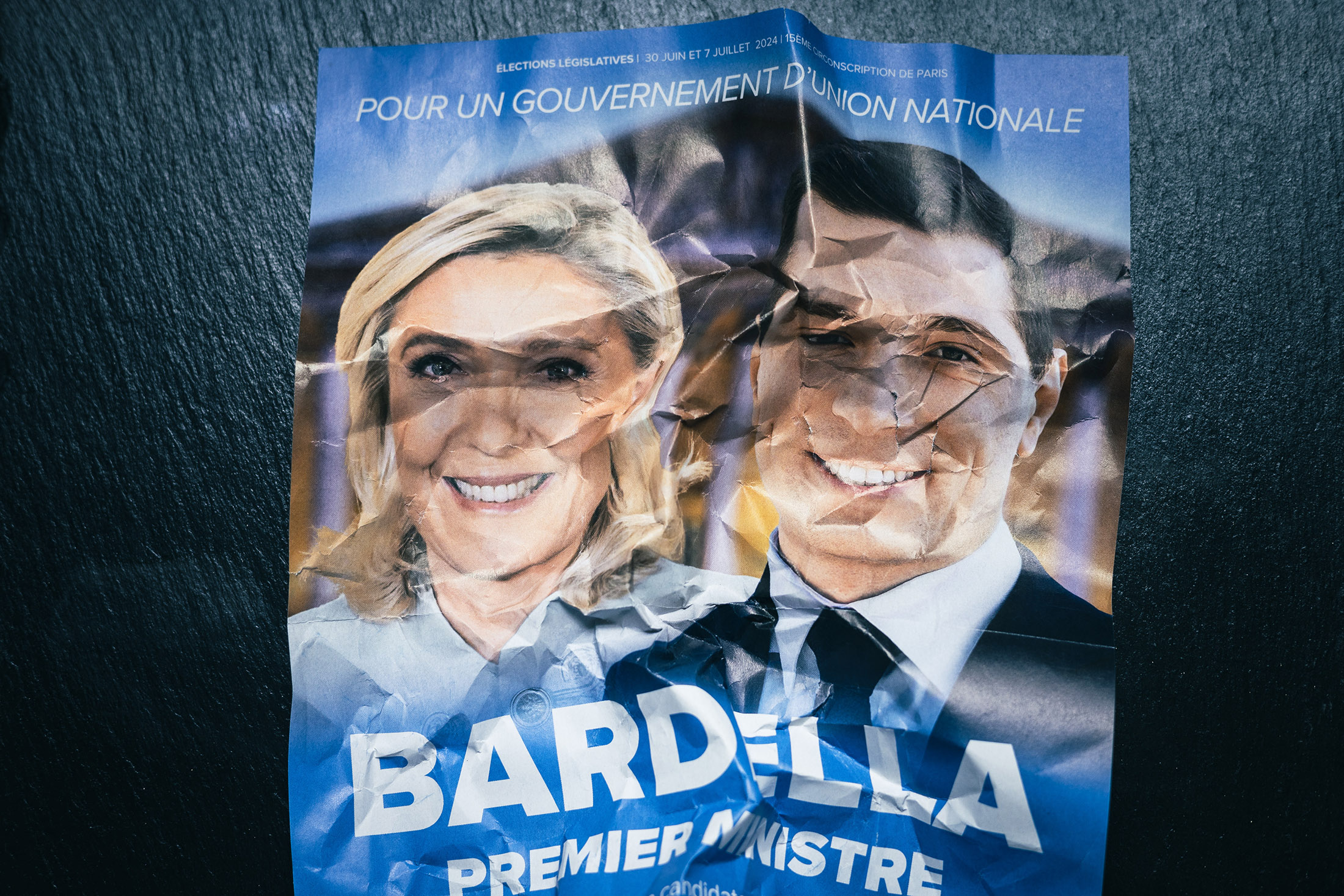

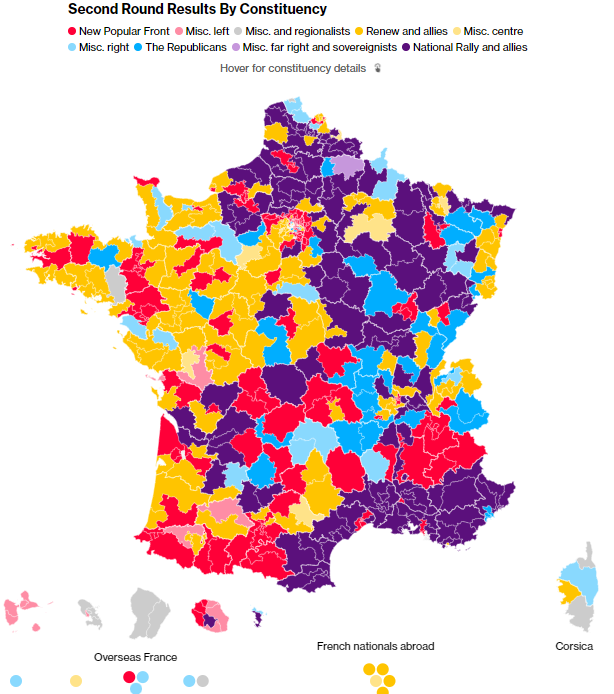

| Welcome to Balance of Power, bringing you the latest in global politics. Readers of the Paris Edition, Weekend Reading and Economics Daily newsletters are also receiving this special edition. To receive Balance of Power going forward, sign up here. So did the gamble pay off? There are many ways to dissect the shocking reversal of political fortunes in the second round of French legislative elections. There is one interpretation where Emmanuel Macron is rubbing his hands in delight, and where the naysayers who thought he was nuts to roll the dice have been proved wrong. He dared voters to invite the far right into government, and after flirting with the idea in the first round, they resoundingly decided “non, merci.” Marine Le Pen’s National Rally came third, as voter turnout was the highest since 1981.  Then there is another, far less charitable take, one where Macron has simply swapped compromise with one extremist group for another and is not really in control of the events he unleashed. The bottom line is that with the far left winning the most seats instead of the far right, he’s simply swapped one devil for another. And the markets see a scenario where if the far left is calling the shots, then all the hard-won pro-business reforms that Macron fought for could be rolled back. That would be disastrous for the country’s finances. And investors hate surprises. Just ask Liz Truss. the shortest-tenured prime minister in UK history. So yes, this pendulum swing in French politics — just as Western leaders are wondering about the stability of their democracies as they watch Joe Biden’s struggles in the US — doesn’t end the chaos. It adds to it. Perhaps the most benign interpretation is that the center-left held, and that days after Labour was restored to power in the UK, it isn’t a foregone conclusion that nationalist populism is here to stay. The biggest certainty is that the so-called Republican Front is stronger than ever. This political tradition dating back to postwar France, where all parties band together to keep the fascists at bay not only held, it was perhaps, a bit too successful. First out the gate was the real winner in all this. Jean-Luc Melenchon, France’s answer to former UK Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn — a 72-year-old left winger who is anti-euro, anti-NATO and unapologetically critical of Israel. He aspires to tax the wealthy, increase the minimum wage and cut the pension age. He wants to open the spending flood gates — or else. Macron had warned, to some derision, that a victory by the far right or left would spark “civil war.” What will the leader who compared himself to the Roman king of gods say now? For Socialist Raphael Glucksmann one thing is clear: “It's the end of the Jupiterianism of the Fifth Republic.”  A discarded National Rally leaflet during voting in Paris today. Photographer: Amaury Cornu/AFP/Getty Images |

| | |

The Highlights |

| The man of the hour is without doubt Melenchon. Before other leaders of the New Popular Front — a makeshift alliance of Socialists, Communists and Greens — could get a word in, the far-left firebrand took center stage at a gathering of followers. “This is extraordinary; two weeks ago you might not have believed this would happen,” Melenchon said, pumping up the crowd with his oratory skills. Later he busted out into a rousing rendition of national anthem, La Marseillaise.  Melenchon reacts during an election night rally. Photographer: Sameer al-Doumy/AFP/Getty Images So who is he? The son of a post office worker and a teacher, both descendants of Spaniards and Italians who emigrated to French Algeria at the turn of the century, Melenchon was born in Tangier, now Morocco, when it was an international zone. He moved to France at the age of 11, studied philosophy, did various jobs including as a journalist and proofreader and got involved in Trotskyist politics. He joined the Socialist Party in 1976 at the age of 25, and was elected to various regional, national and European legislative positions. Why are investors afraid of him? Melenchon often regales crowds with the evils of “extreme markets that transform suffering, misery and abandonment into gold and money.” This is probably the closest markets have come to taking his words seriously. Melenchon considers France a country “with huge wealth that is badly distributed.” He’s a fan of former Venezuelan leader Hugo Chavez and Cuba’s Fidel Castro and like them launches into fiery speeches, often without a teleprompter and using his trademark mix of humor and anger. Either way, the squabbling has already begun — and neither the euro nor France’s yield spreads will like the noise coming out of Paris. The tone of defiance that Melenchon has struck will not sit well with bond investors wary of what the implications of his rhetoric — now no longer an idle threat — will mean for France’s deficit. The election is the beginning of a more turbulent period, according to executives gathered in southern France this weekend. One of the biggest hits could be on the image of France as a top European destination for foreign investment. The country was already entering uncharted territory with the prospect of a far-right government or a gridlocked one. Now the most likely one is the one that France’s 1% feared the most. Jordan Bardella, just a week ago, could already picture himself perhaps as becoming France's youngest prime minister. It was not to be and the 28-year-old and heir apparent to Le Pen is not a gracious loser. He is crying foul about the “unnatural” alliances that shut his party out. Speaking at a rally, he complained that “voting arrangements orchestrated from the Elysee palace by an isolated president and an incendiary left won’t lead anywhere.”  Macron has kept a low profile, and continues to do so. In a statement, his office said he would wait until the formation of the new National Assembly was completed before making any decisions: “In his role as guarantor of our institutions, the president will ensure that the sovereign choice of the French people is respected.” Macron, who usually loves to talk, isn’t talking and is keeping cards close to his chest. Gabriel Attal is falling on his sword. France’s youngest prime minister, hand-picked by Macron as part of his plan to revive his government, says he’ll submit his resignation on Monday. The move, while perhaps not surprising, sends a message that he is differentiating himself from Macron (who could of course ask him to stay on for the Olympics that kick off in Paris this month).  Le Pen speaks to the press following her party’s defeat today. Photographer: Carl Court/Getty Images Meanwhile, Le Pen is trying to pretend she didn’t have a bad night. Speaking to TF1 Television, she said: “The tide is rising, it hasn’t risen high enough this time, but it’s still rising.” Asked if Macron should resign, she says she is calling for nothing tonight. As we wrote in our Big Take, Le Pen betrayed her own father and political roots to bring her party this close to power. It wasn’t enough. |

Chart of the Day |

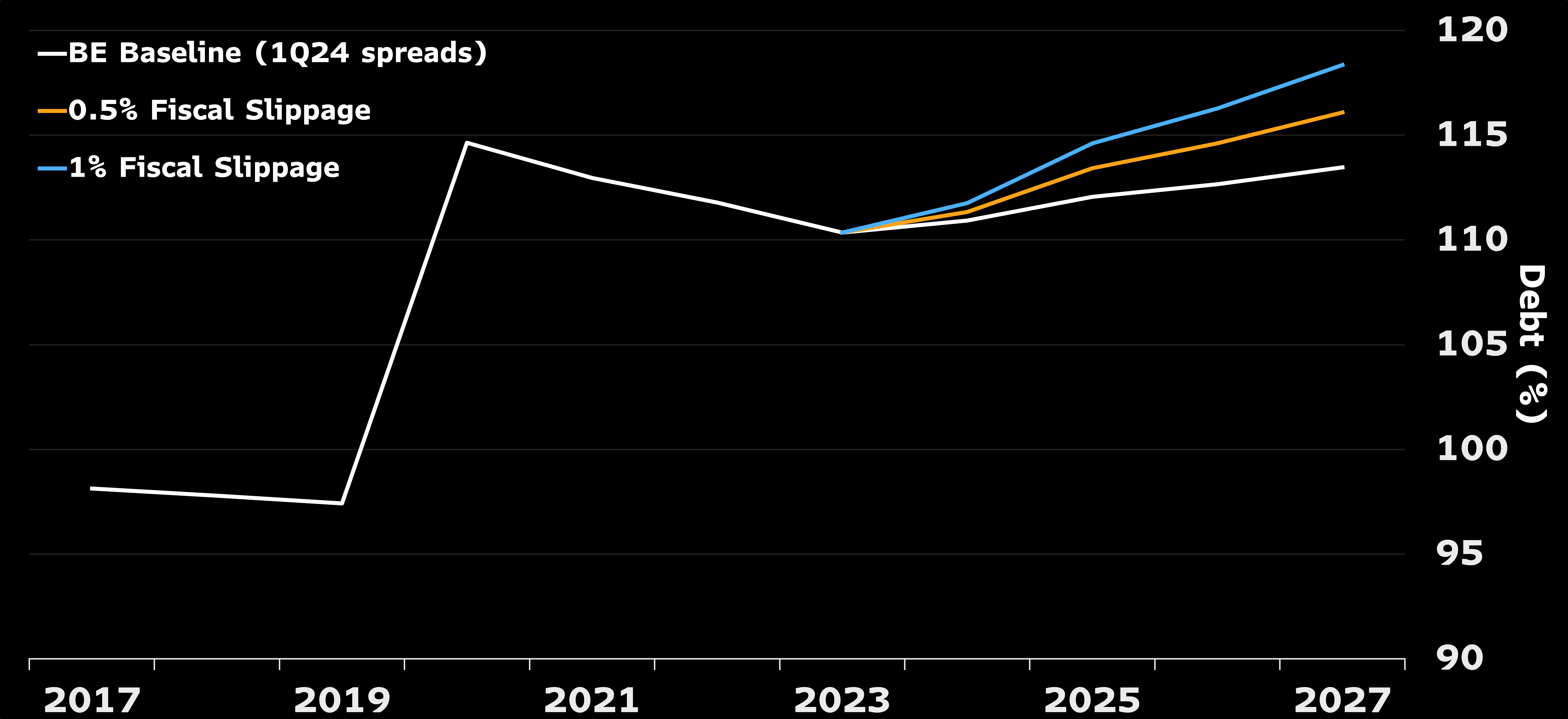

Bloomberg Economics The shock election win for the left in France will probably herald protracted uncertainty. If and when a government is formed, Bloomberg economists Eleonora Mavroeidi, Maeva Cousin and Jamie Rush see a “quite modest” impact on the public finances at first, but more worrying effects further out. They plot out two possible scenarios. One is a coalition that delivers a net fiscal giveaway of 0.5% of output that would keep the spread of French bonds over German equivalents at about 75 basis points, roughly the average since the snap election election was called. The other is a bigger giveaway totalling 1% of gross domestic product. They reckon this would widen the spread to 100 basis points — and swell debt as percentage of output to more than 118% of output. |

And Finally |

| The Clash’s London Calling was booming at the France Unbowed election night headquarters, located in a square in a northern area of Paris known for drug trafficking and squalor. Hundreds gathered in front of a stage from which party leaders Melenchon and Manuel Bompard vowed to take power in the French legislature. Beer and wine flowed and the choice of music was telling including from the Spanish resistance. The song from the English punk rock band of the 1970s was a flick to Labour’s victory across the Channel. Also playing? “On lache rien,” that can be translated to mean “We won’t give in to anything.” At one point an image of Bardella flicked onscreen. There was loud booing and he was drowned out with anti-fascist chants.  A supporter of left-wing party La France Insoumise holds a Palestinian flag during the election night rally in Paris. Photographer: Sameer al-Doumy/AFP/Getty Images |

|

| Follow Us | |||

|

|

|