I pour tremendous time, thought, love, and resources into Brain Pickings, which remains free. If you find any joy and stimulation here, please consider supporting my labor of love with a recurring monthly donation of your choosing, between a cup of tea and a good dinner:  You can also become a one-time patron with a single donation in any amount:  And if you've already donated, from the bottom of my heart: THANK YOU. |

|  Hello, John Do! If you missed last week's edition – a remarkable Danish illustrated meditation on life with and after loss, poet Sarah Kay on how we measure creative success as individuals and as a culture, Mendelssohn on creative integrity, and more – you can catch up right here. If you're enjoying this newsletter, please consider supporting my labor of love with a donation – I spend countless hours and tremendous resources on it, and every little bit of support helps enormously. Hello, John Do! If you missed last week's edition – a remarkable Danish illustrated meditation on life with and after loss, poet Sarah Kay on how we measure creative success as individuals and as a culture, Mendelssohn on creative integrity, and more – you can catch up right here. If you're enjoying this newsletter, please consider supporting my labor of love with a donation – I spend countless hours and tremendous resources on it, and every little bit of support helps enormously.

|

“There is no love of life without despair of life,” wrote Albert Camus — a man who in the midst of World War II, perhaps the darkest period in human history, saw grounds for luminous hope and issued a remarkable clarion call for humanity to rise to its highest potential on those grounds. It was his way of honoring the same duality that artist Maira Kalman would capture nearly a century later in her marvelous meditation on the pursuit of happiness, where she observed: “We hope. We despair. We hope. We despair. That is what governs us. We have a bipolar system.” In my own reflections on hope, cynicism, and the stories we tell ourselves, I’ve considered the necessity of these two poles working in concert. Indeed, the stories we tell ourselves about these poles matter. The stories we tell ourselves about our public past shape how we interpret and respond to and show up for the present. The stories we tell ourselves about our private pasts shape how we come to see our personhood and who we ultimately become. The thin line between agency in victimhood is drawn in how we tell those stories. The language in which we tell ourselves these stories matters tremendously, too, and no writer has weighed the complexities of sustaining hope in our times of readily available despair more thoughtfully and beautifully, nor with greater nuance, than Rebecca Solnit does in Hope in the Dark: Untold Histories, Wild Possibilities (public library).  Rebecca Solnit (Photograph: Sallie Dean Shatz) Expanding upon her previous writings on hope, Solnit writes in the foreword to the 2016 edition of this foundational text of modern civic engagement:  Hope is a gift you don’t have to surrender, a power you don’t have to throw away. And though hope can be an act of defiance, defiance isn’t enough reason to hope. But there are good reasons. Hope is a gift you don’t have to surrender, a power you don’t have to throw away. And though hope can be an act of defiance, defiance isn’t enough reason to hope. But there are good reasons.

Solint — one of the most singular, civically significant, and poetically potent voices of our time, emanating echoes of Virginia Woolf’s luminous prose and Adrienne Rich’s unflinching political conviction — originally wrote these essays in 2003, six weeks after the start of Iraq war, in an effort to speak “directly to the inner life of the politics of the moment, to the emotions and preconceptions that underlie our political positions and engagements.” Although the specific conditions of the day may have shifted, their undergirding causes and far-reaching consequences have only gained in relevance and urgency in the dozen years since. This slim book of tremendous potency is therefore, today more than ever, an indispensable ally to every thinking, feeling, civically conscious human being. Solnit looks back on this seemingly distant past as she peers forward into the near future:  The moment passed long ago, but despair, defeatism, cynicism, and the amnesia and assumptions from which they often arise have not dispersed, even as the most wildly, unimaginably magnificent things came to pass. There is a lot of evidence for the defense… Progressive, populist, and grassroots constituencies have had many victories. Popular power has continued to be a profound force for change. And the changes we’ve undergone, both wonderful and terrible, are astonishing. The moment passed long ago, but despair, defeatism, cynicism, and the amnesia and assumptions from which they often arise have not dispersed, even as the most wildly, unimaginably magnificent things came to pass. There is a lot of evidence for the defense… Progressive, populist, and grassroots constituencies have had many victories. Popular power has continued to be a profound force for change. And the changes we’ve undergone, both wonderful and terrible, are astonishing.

[…] This is an extraordinary time full of vital, transformative movements that could not be foreseen. It’s also a nightmarish time. Full engagement requires the ability to perceive both.

Illustration by Charlotte Pardi from Cry, Heart, But Never Break by Glenn Ringtved With an eye to such disheartening developments as climate change, growing income inequality, and the rise of Silicon Valley as a dehumanizing global superpower of automation, Solnit invites us to be equally present for the counterpoint:  Hope doesn’t mean denying these realities. It means facing them and addressing them by remembering what else the twenty-first century has brought, including the movements, heroes, and shifts in consciousness that address these things now. Hope doesn’t mean denying these realities. It means facing them and addressing them by remembering what else the twenty-first century has brought, including the movements, heroes, and shifts in consciousness that address these things now.

Enumerating Edward Snowden, marriage equality, and Black Lives Matter among those, she adds:  This has been a truly remarkable decade for movement-building, social change, and deep, profound shifts in ideas, perspective, and frameworks for broad parts of the population (and, of course, backlashes against all those things). This has been a truly remarkable decade for movement-building, social change, and deep, profound shifts in ideas, perspective, and frameworks for broad parts of the population (and, of course, backlashes against all those things).

With great care, Solnit — whose mind remains the sharpest instrument of nuance I’ve encountered — maps the uneven terrain of our grounds for hope:  It’s important to say what hope is not: it is not the belief that everything was, is, or will be fine. The evidence is all around us of tremendous suffering and tremendous destruction. The hope I’m interested in is about broad perspectives with specific possibilities, ones that invite or demand that we act. It’s also not a sunny everything-is-getting-better narrative, though it may be a counter to the everything-is-getting-worse narrative. You could call it an account of complexities and uncertainties, with openings. It’s important to say what hope is not: it is not the belief that everything was, is, or will be fine. The evidence is all around us of tremendous suffering and tremendous destruction. The hope I’m interested in is about broad perspectives with specific possibilities, ones that invite or demand that we act. It’s also not a sunny everything-is-getting-better narrative, though it may be a counter to the everything-is-getting-worse narrative. You could call it an account of complexities and uncertainties, with openings.

Solnit’s conception of hope reminds me of the great existential psychiatrist Irvin D. Yalom’s conception of meaning: “The search for meaning, much like the search for pleasure,” he wrote, “must be conducted obliquely.” That is, it must take place in the thrilling and terrifying terra incognita that lies between where we are and where we wish to go, ultimately shaping where we do go. Solnit herself has written memorably about how we find ourselves by getting lost, and finding hope seems to necessitate a similar surrender to uncertainty. She captures this idea beautifully:  Hope locates itself in the premises that we don’t know what will happen and that in the spaciousness of uncertainty is room to act. When you recognize uncertainty, you recognize that you may be able to influence the outcomes — you alone or you in concert with a few dozen or several million others. Hope is an embrace of the unknown and the unknowable, an alternative to the certainty of both optimists and pessimists. Optimists think it will all be fine without our involvement; pessimists take the opposite position; both excuse themselves from acting. It’s the belief that what we do matters even though how and when it may matter, who and what it may impact, are not things we can know beforehand. We may not, in fact, know them afterward either, but they matter all the same, and history is full of people whose influence was most powerful after they were gone. Hope locates itself in the premises that we don’t know what will happen and that in the spaciousness of uncertainty is room to act. When you recognize uncertainty, you recognize that you may be able to influence the outcomes — you alone or you in concert with a few dozen or several million others. Hope is an embrace of the unknown and the unknowable, an alternative to the certainty of both optimists and pessimists. Optimists think it will all be fine without our involvement; pessimists take the opposite position; both excuse themselves from acting. It’s the belief that what we do matters even though how and when it may matter, who and what it may impact, are not things we can know beforehand. We may not, in fact, know them afterward either, but they matter all the same, and history is full of people whose influence was most powerful after they were gone.

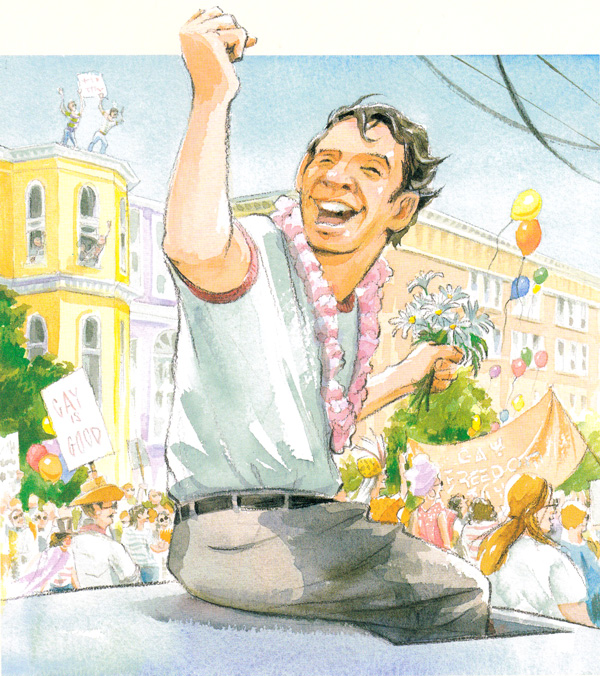

Illustration from The Harvey Milk Story, a picture-book biography of the slain LGBT rights pioneer Amid a 24-hour news cycle that nurses us on the illusion of immediacy, this recognition of incremental progress and the long gestational period of consequences — something at the heart of every major scientific revolution that has changed our world — is perhaps our most essential yet most endangered wellspring of hope. Solnit reminds us, for instance, that women’s struggle for the right to vote took seven decades:  For a time people liked to announce that feminism had failed, as though the project of overturning millennia of social arrangements should achieve its final victories in a few decades, or as though it had stopped. Feminism is just starting, and its manifestations matter in rural Himalayan villages, not just first-world cities. For a time people liked to announce that feminism had failed, as though the project of overturning millennia of social arrangements should achieve its final victories in a few decades, or as though it had stopped. Feminism is just starting, and its manifestations matter in rural Himalayan villages, not just first-world cities.

She considers one particularly prominent example of this cumulative cataclysm — the Arab Spring, “an extraordinary example of how unpredictable change is and how potent popular power can be,” the full meaning of and conclusions from which we are yet to draw. Although our cultural lore traces the spark of the Arab Spring to the moment Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire in an act of protest, Solnit traces the unnoticed accretion of tinder across space and time:  You can tell the genesis story of the Arab Spring other ways. The quiet organizing going on in the shadows beforehand matters. So does the comic book about Martin Luther King and civil disobedience that was translated into Arabic and widely distributed in Egypt shortly before the Arab Spring. You can tell of King’s civil disobedience tactics being inspired by Gandhi’s tactics, and Gandhi’s inspired by Tolstoy and the radical acts of noncooperation and sabotage of British women suffragists. So the threads of ideas weave around the world and through the decades and centuries. You can tell the genesis story of the Arab Spring other ways. The quiet organizing going on in the shadows beforehand matters. So does the comic book about Martin Luther King and civil disobedience that was translated into Arabic and widely distributed in Egypt shortly before the Arab Spring. You can tell of King’s civil disobedience tactics being inspired by Gandhi’s tactics, and Gandhi’s inspired by Tolstoy and the radical acts of noncooperation and sabotage of British women suffragists. So the threads of ideas weave around the world and through the decades and centuries.

In a brilliant counterpoint to Malcolm Gladwell’s notoriously short-sighted view of social change, Solnit sprouts a mycological metaphor for this imperceptible, incremental buildup of influence and momentum:  After a rain mushrooms appear on the surface of the earth as if from nowhere. Many do so from a sometimes vast underground fungus that remains invisible and largely unknown. What we call mushrooms mycologists call the fruiting body of the larger, less visible fungus. Uprisings and revolutions are often considered to be spontaneous, but less visible long-term organizing and groundwork — or underground work — often laid the foundation. Changes in ideas and values also result from work done by writers, scholars, public intellectuals, social activists, and participants in social media. It seems insignificant or peripheral until very different outcomes emerge from transformed assumptions about who and what matters, who should be heard and believed, who has rights. After a rain mushrooms appear on the surface of the earth as if from nowhere. Many do so from a sometimes vast underground fungus that remains invisible and largely unknown. What we call mushrooms mycologists call the fruiting body of the larger, less visible fungus. Uprisings and revolutions are often considered to be spontaneous, but less visible long-term organizing and groundwork — or underground work — often laid the foundation. Changes in ideas and values also result from work done by writers, scholars, public intellectuals, social activists, and participants in social media. It seems insignificant or peripheral until very different outcomes emerge from transformed assumptions about who and what matters, who should be heard and believed, who has rights.

Ideas at first considered outrageous or ridiculous or extreme gradually become what people think they’ve always believed. How the transformation happened is rarely remembered, in part because it’s compromising: it recalls the mainstream when the mainstream was, say, rabidly homophobic or racist in a way it no longer is; and it recalls that power comes from the shadows and the margins, that our hope is in the dark around the edges, not the limelight of center stage. Our hope and often our power. […] Change is rarely straightforward… Sometimes it’s as complex as chaos theory and as slow as evolution. Even things that seem to happen suddenly arise from deep roots in the past or from long-dormant seeds.

One of Beatrix Potter’s little-known scientific studies and illustrations of mushrooms And yet Solnit’s most salient point deals with what comes after the revolutionary change — with the notion of victory not as a destination but as a starting point for recommitment and continual nourishment of our fledgling ideals:  A victory doesn’t mean that everything is now going to be nice forever and we can therefore all go lounge around until the end of time. Some activists are afraid that if we acknowledge victory, people will give up the struggle. I’ve long been more afraid that people will give up and go home or never get started in the first place if they think no victory is possible or fail to recognize the victories already achieved. Marriage equality is not the end of homophobia, but it’s something to celebrate. A victory is a milestone on the road, evidence that sometimes we win, and encouragement to keep going, not to stop. A victory doesn’t mean that everything is now going to be nice forever and we can therefore all go lounge around until the end of time. Some activists are afraid that if we acknowledge victory, people will give up the struggle. I’ve long been more afraid that people will give up and go home or never get started in the first place if they think no victory is possible or fail to recognize the victories already achieved. Marriage equality is not the end of homophobia, but it’s something to celebrate. A victory is a milestone on the road, evidence that sometimes we win, and encouragement to keep going, not to stop.

Solnit examines this notion more closely in one of the original essays from the book, titled “Changing the Imagination of Change” — a meditation of even more acute timeliness today, more than a decade later, in which she writes:  Americans are good at responding to crisis and then going home to let another crisis brew both because we imagine that the finality of death can be achieved in life — it’s called happily ever after in personal life, saved in politics — and because we tend to think political engagement is something for emergencies rather than, as people in many other countries (and Americans at other times) have imagined it, as a part and even a pleasure of everyday life. The problem seldom goes home. Americans are good at responding to crisis and then going home to let another crisis brew both because we imagine that the finality of death can be achieved in life — it’s called happily ever after in personal life, saved in politics — and because we tend to think political engagement is something for emergencies rather than, as people in many other countries (and Americans at other times) have imagined it, as a part and even a pleasure of everyday life. The problem seldom goes home.

[…] Going home seems to be a way to abandon victories when they’re still delicate, still in need of protection and encouragement. Human babies are helpless at birth, and so perhaps are victories before they’ve been consolidated into the culture’s sense of how things should be. I wonder sometimes what would happen if victory was imagined not just as the elimination of evil but the establishment of good — if, after American slavery had been abolished, Reconstruction’s promises of economic justice had been enforced by the abolitionists, or, similarly, if the end of apartheid had been seen as meaning instituting economic justice as well (or, as some South Africans put it, ending economic apartheid). It’s always too soon to go home. Most of the great victories continue to unfold, unfinished in the sense that they are not yet fully realized, but also in the sense that they continue to spread influence. A phenomenon like the civil rights movement creates a vocabulary and a toolbox for social change used around the globe, so that its effects far outstrip its goals and specific achievements — and failures.

Invoking James Baldwin’s famous proclamation that “not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced,” Solnit writes:  It’s important to emphasize that hope is only a beginning; it’s not a substitute for action, only a basis for it. It’s important to emphasize that hope is only a beginning; it’s not a substitute for action, only a basis for it.

What often obscures our view of hope, she argues, is a kind of collective amnesia that lets us forget just how far we’ve come as we grow despondent over how far we have yet to go. She writes:  Amnesia leads to despair in many ways. The status quo would like you to believe it is immutable, inevitable, and invulnerable, and lack of memory of a dynamically changing world reinforces this view. In other words, when you don’t know how much things have changed, you don’t see that they are changing or that they can change. Amnesia leads to despair in many ways. The status quo would like you to believe it is immutable, inevitable, and invulnerable, and lack of memory of a dynamically changing world reinforces this view. In other words, when you don’t know how much things have changed, you don’t see that they are changing or that they can change.

Illustration by Isabelle Arsenault from Mr. Gauguin’s Heart by Marie-Danielle Croteau, the story of how Paul Gauguin used the grief of his childhood as a catalyst for a lifetime of art This lack of a long view is perpetuated by the media, whose raw material — the very notion of “news” — divorces us from the continuity of life and keeps us fixated on the current moment in artificial isolate. Meanwhile, Solnit argues in a poignant parallel, such amnesia poisons and paralyzes our collective conscience by the same mechanism that depression poisons and paralyzes the private psyche — we come to believe that the acute pain of the present is all that will ever be and cease to believe that things will look up. She writes:  There’s a public equivalent to private depression, a sense that the nation or the society rather than the individual is stuck. Things don’t always change for the better, but they change, and we can play a role in that change if we act. Which is where hope comes in, and memory, the collective memory we call history. There’s a public equivalent to private depression, a sense that the nation or the society rather than the individual is stuck. Things don’t always change for the better, but they change, and we can play a role in that change if we act. Which is where hope comes in, and memory, the collective memory we call history.

A dedicated rower, Solnit ends with the perfect metaphor:  You row forward looking back, and telling this history is part of helping people navigate toward the future. We need a litany, a rosary, a sutra, a mantra, a war chant for our victories. The past is set in daylight, and it can become a torch we can carry into the night that is the future. You row forward looking back, and telling this history is part of helping people navigate toward the future. We need a litany, a rosary, a sutra, a mantra, a war chant for our victories. The past is set in daylight, and it can become a torch we can carry into the night that is the future.

Hope in the Dark is a robust anchor of intelligent idealism amid our tumultuous era of disorienting defeatism — a vitalizing exploration of how we can withstand the marketable temptations of false hope and easy despair. Complement it with Camus on how to ennoble our minds in dark times and Viktor Frankl on why idealism is the best realism, then revisit Solnit on the rewards of walking, what reading does for the human spirit, and how modern noncommunication is changing our experience of time, solitude, and communion.

“It came to me while picking beans, the secret of happiness,” botanist and storyteller Robin Wall Kimmerer wrote in her beautiful meditation on gardening and life’s largest satisfactions a century after Virginia Woolf’s unforgettable flower-garden epiphany about the meaning of life. Surely, the garden, quite apart from its tangible satisfactions, fertilizes the imagination with ample metaphors for the tilling of our interior landscape — metaphors nowhere more precise and poetic than in the opening pages of psychotherapist and writer Janna Malamud Smith’s altogether magnificent exploration of the creative life, An Absorbing Errand: How Artists and Craftsmen Make Their Way to Mastery (public library). Although Malamud Smith had grown up amid artists of various stripes, it wasn’t until she watched her elderly mother’s immersive and invigorating communion with the garden that she grasped the underlying psychological pattern of creative work. She writes:  The good life is lived best by those with gardens — a truth that was already a gnarled old vine in ancient Rome, but a sturdy one that still bears fruit. I don’t mean one must garden qua garden… I mean rather the moral equivalent of a garden — the virtual garden. I posit that life is better when you possess a sustaining practice that holds your desire, demands your attention, and requires effort; a plot of ground that gratifies the wish to labor and create — and, by so doing, to rule over an imagined world of your own. The good life is lived best by those with gardens — a truth that was already a gnarled old vine in ancient Rome, but a sturdy one that still bears fruit. I don’t mean one must garden qua garden… I mean rather the moral equivalent of a garden — the virtual garden. I posit that life is better when you possess a sustaining practice that holds your desire, demands your attention, and requires effort; a plot of ground that gratifies the wish to labor and create — and, by so doing, to rule over an imagined world of your own.

[…] As with the literal act of gardening, pursuing any practice seriously is a generative, hardy way to live in the world. You are in charge (as much as we can ever pretend to be — sometimes like a sea captain hugging the rail in a hurricane); you plan; you design; you labor; you struggle. And your reward is that in some seasons you create a gratifying bounty.

Illustration by Emily Hughes from Little Gardener But between the garden and the gardening lies the essential transmutation of intention into mastery. I’m reminded of writer and art curator Sarah Lewis’s elegant definition of mastery as “not merely a commitment to a goal, but to a curved-line, constant pursuit.” Malamud Smith considers the heart of that commitment:  One must work hard to learn technique and form, and equally hard to learn how to bear the angst of creativity itself… The effort brings with it a whole herd of psychological obstacles — rather like a wooly mass of obdurate sheep settled on the road blocking your car. For you to move forward, these creatures must be outwitted, dispersed, befriended, or herded, their impeding genius somehow overcome or co-opted. One must work hard to learn technique and form, and equally hard to learn how to bear the angst of creativity itself… The effort brings with it a whole herd of psychological obstacles — rather like a wooly mass of obdurate sheep settled on the road blocking your car. For you to move forward, these creatures must be outwitted, dispersed, befriended, or herded, their impeding genius somehow overcome or co-opted.

In a sentiment that calls to mind Adrienne Rich’s terrific tribute to Marie Curie — “her wounds came from the same source as her power” — Malamud Smith writes:  You may be unaware of how the necessary struggles of your own unconscious mind, if misunderstood, will bruise your heart, arrest your efforts prematurely, and prevent your staying absorbed in your errand. Yet, the same struggles, appreciated, will enable your creativity and the larger processes of mastery. You may be unaware of how the necessary struggles of your own unconscious mind, if misunderstood, will bruise your heart, arrest your efforts prematurely, and prevent your staying absorbed in your errand. Yet, the same struggles, appreciated, will enable your creativity and the larger processes of mastery.

Illustration by Julie Paschkis for Pablo Neruda: Poet of the People by Monica Brown She considers why the mastery of creative work beckons us at all — how it extends its promise of making us “feel stimulated, warm, slightly elated, or otherwise moved; content; purposeful,” of aligning us with our innermost selves:  Whether by design or by accident, many of us seem to find enduring gratification in struggling to master and then repeatedly applying some difficult skill that allows us at once to realize and express ourselves. Whether by design or by accident, many of us seem to find enduring gratification in struggling to master and then repeatedly applying some difficult skill that allows us at once to realize and express ourselves.

Echoing Wendell Berry’s beautiful assertion that in true solitude “one’s inner voice becomes audible,” she adds:  The feelings and purposes around art-making … ricochet among private, public, and communal places, but the creative process often demands seclusion to germinate its seed. The feelings and purposes around art-making … ricochet among private, public, and communal places, but the creative process often demands seclusion to germinate its seed.

She returns to the metaphor of the garden:  The work grows as our minds (conscious and unconscious) and our bodies would have it grow. Technique may require discipline and set the order of things, apprenticeships may demand periods of subordination, but the imaginative acts that propel the effort are themselves serendipitous. In your garden you may set out to clip the roses, but you notice a weed you want to pull from among the coreopsis, except that first there is a rogue branch to be snipped from the holly shrub—and on and on until dark finally settles, ending your day. An occasional task has to be done just now and just so. But mostly, you delight in meandering, allowing the work to command your attention variously — with its method inscribed by the way you encounter your plants. The work grows as our minds (conscious and unconscious) and our bodies would have it grow. Technique may require discipline and set the order of things, apprenticeships may demand periods of subordination, but the imaginative acts that propel the effort are themselves serendipitous. In your garden you may set out to clip the roses, but you notice a weed you want to pull from among the coreopsis, except that first there is a rogue branch to be snipped from the holly shrub—and on and on until dark finally settles, ending your day. An occasional task has to be done just now and just so. But mostly, you delight in meandering, allowing the work to command your attention variously — with its method inscribed by the way you encounter your plants.

Such work guards a quality of timelessness within an ever-more-time-bound world.

Illustration by Maurice Sendak from Open House for Butterflies by Ruth Krauss This timelessness is rather the astonishing elasticity of time that Virginia Woolf so memorably described — a state of suspended and infinitely extended attention partway between Gaston Bachelard’s intuition of the instant and Einstein’s eternity of truth and beauty. Malamud Smith considers the singular temporal dimension of creative work:  One pleasure of art-making is its resolute inefficiency… The necessary thought may come today or next week. Yet it’s not the same as leisure. The struggle toward that next thought is rigorous, held within an isometric tension… You must hold still and wait, and yet you must push forward. One pleasure of art-making is its resolute inefficiency… The necessary thought may come today or next week. Yet it’s not the same as leisure. The struggle toward that next thought is rigorous, held within an isometric tension… You must hold still and wait, and yet you must push forward.

Still, in his 1948 manifesto for why leisure is the basis of culture, the German philosopher Joseph Pieper made an elegant case for why unrushed time and unburdened cognitive space are essential for creative work. Malamud Smith recognizes this notion, too, albeit somewhat differently:  Because the point of arrival is enigmatic, elusive, receding, because it wavers like a mirage on the road, always before us and only briefly with us, devoting oneself to mastering a practice unexpectedly leads through a time warp where past, present, and future commingle. I find the contradictory notion comforting. Contemporary life is all excerpts, fragments, reversals, and interruptions; it offends and delights us with its astounding, noisy discontinuity, but the work of mastery is very much as it was when artists thousands of years ago carved Cycladic figures or cast the Benin gold. Because the point of arrival is enigmatic, elusive, receding, because it wavers like a mirage on the road, always before us and only briefly with us, devoting oneself to mastering a practice unexpectedly leads through a time warp where past, present, and future commingle. I find the contradictory notion comforting. Contemporary life is all excerpts, fragments, reversals, and interruptions; it offends and delights us with its astounding, noisy discontinuity, but the work of mastery is very much as it was when artists thousands of years ago carved Cycladic figures or cast the Benin gold.

[…] Our common creative labors restore older, more familiar rhythms of humanity, and by doing so they ground us and temper the particular fragmentation and disconnections that define our age.

In the remainder of the wholly invigorating An Absorbing Errand, Malamud Smith goes on to explore how identity, fear, shame, solitude, and other facets of the human experience illuminate the psychoemotional machinery of that tempering in creative work. Complement it with Dani Shapiro on the pleasures and perils of the creative life, Anne Truitt on the vital difference between being an artist and doing art, and Agnes Martin on cultivating the optimal atmosphere for creative work. Thanks, Dani

“One can’t write directly about the soul,” Virginia Woolf lamented. “Looked at, it vanishes.” A century later, we may have rendered the notion of the soul unfashionable — arguably, to our own detriment — but the puzzlement at the heart of Woolf’s observation hasn’t left us. If anything, we’ve recontextualized it as the problem of consciousness and taken it to the neuroscience lab, where it has only grown more perplexing — for, as Marilynne Robinson observed in her magnificent meditation on consciousness, the usefulness of the soul, and the limits of neuroscience, “on scrutiny the physical is as elusive as anything to which a name can be given.” One of the finest, most dimensional explorations of consciousness comes from mathematician turned physician and writer Israel Rosenfield in his 1992 masterwork The Strange, Familiar, and Forgotten: An Anatomy of Consciousness (public library) — a trailblazing inquiry into the nature and structure of consciousness, and one of Oliver Sacks’s favorite books.  Israel Rosenfield (Photograph: Catherine Temerson) Rosenfield, whom Dr. Sacks rightly celebrated as “a powerful and original thinker,” contextualizes what makes the question of consciousness so alluring yet so mystifying:  What we say and do often hides motives that we keep from others and even from ourselves. Modern psychology began when this observation, as old as the writing of history, was turned into a principle: that our thoughts and actions are to a great extent determined by ideas, memories, and drives that are unconscious and inaccessible to conscious thought; that unknowable forces determine our actions. Thus the study of the unconscious became the cornerstone of twentieth-century psychology. Consciousness itself was ignored, since after all elucidating the unconscious seemed to tell us so much. People came to presume that when they talked of their “memories,” they meant experiences and learning that were carefully stored away in their brains and could be brought into consciousness, or made conscious. But this was to ignore the possibility that memories were in fact part of the very structure of consciousness: not only can there be no such thing as a memory without there being consciousness, but consciousness and memory are in a certain sense inseparable, and understanding one requires understanding the other. What we say and do often hides motives that we keep from others and even from ourselves. Modern psychology began when this observation, as old as the writing of history, was turned into a principle: that our thoughts and actions are to a great extent determined by ideas, memories, and drives that are unconscious and inaccessible to conscious thought; that unknowable forces determine our actions. Thus the study of the unconscious became the cornerstone of twentieth-century psychology. Consciousness itself was ignored, since after all elucidating the unconscious seemed to tell us so much. People came to presume that when they talked of their “memories,” they meant experiences and learning that were carefully stored away in their brains and could be brought into consciousness, or made conscious. But this was to ignore the possibility that memories were in fact part of the very structure of consciousness: not only can there be no such thing as a memory without there being consciousness, but consciousness and memory are in a certain sense inseparable, and understanding one requires understanding the other.

[…] Human memory may be unlike anything we have thus far imagined or successfully built a model for. And consciousness may be the reason why.

One of the most remarkable aspects of consciousness, Rosenfield points out, is “its utter subjectivity, the uniqueness of each individual human perspective.” This makes our capacity for empathy an extraordinary feat, for it requires that we acknowledge the subjectivity of our own reality and accommodate that of another, and yet we remain by and large entrapped in our subjectivity. As the great physicist David Bohm memorably articulated the problem, “Reality is what we take to be true. What we take to be true is what we believe… What we believe determines what we take to be true.” Rosenfield captures this paradox:  In this subjectivity, oddly, we nonetheless feel or believe we are experiencing the objective truth about the world, and we call that knowledge; we usually think of knowledge as something that can be understood and also transmitted from one person to another. In this subjectivity, oddly, we nonetheless feel or believe we are experiencing the objective truth about the world, and we call that knowledge; we usually think of knowledge as something that can be understood and also transmitted from one person to another.

Art by Tove Jansson for a rare edition of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland But this, Rosenfield cautions, seeds one of our gravest misconceptions about consciousness — the expectation that it is contained in specific units of knowledge or records, so to speak, of sensory experience, stored in particular areas of the brain. Although scientists have shown that specific brain tissues do respond to stimuli like shape, color, and motion, and neuroscience has made tremendous strides in the quarter-century since the book was published, Rosenfield’s critique of the broader limitations of such neurophysiological hunts for the seedbed of consciousness remains remarkably astute:  If one thinks about the ordinary human experience of being conscious, of being aware and alert to the meaning of one’s ongoing experiences, it seems unlikely that perceptions become conscious by these re-creations or representations in the brain, however complex they are supposed to be. This notion presupposes a static model of brain function; but consciousness has a temporal flow, a continuity over time, that cannot be accounted for by the neuroscientists’ claim that specific parts of the brain are responding to the presence of particular stimuli at a given moment. Our perceptions are part of a “stream of consciousness,” part of a continuity of experience that the neuroscientific models and descriptions fail to capture; their categories of color, say, or smell, or sound, or motion are discrete entities independent of time. But … a sense of consciousness comes precisely from the flow of perceptions, from the relations among them (both spatial and temporal), from the dynamic but constant relation to them as governed by one unique personal perspective sustained throughout a conscious life; this dynamic sense of consciousness eludes the neuroscientists’ analyses. Compared to it, units of “knowledge” such as we can transmit or record in books or images are but instant snapshots taken in a dynamic flow of uncontainable, unrepeatable, and inexpressible experience. And it is an unwarranted mistake to associate these snapshots with material “stored” in the brain. If one thinks about the ordinary human experience of being conscious, of being aware and alert to the meaning of one’s ongoing experiences, it seems unlikely that perceptions become conscious by these re-creations or representations in the brain, however complex they are supposed to be. This notion presupposes a static model of brain function; but consciousness has a temporal flow, a continuity over time, that cannot be accounted for by the neuroscientists’ claim that specific parts of the brain are responding to the presence of particular stimuli at a given moment. Our perceptions are part of a “stream of consciousness,” part of a continuity of experience that the neuroscientific models and descriptions fail to capture; their categories of color, say, or smell, or sound, or motion are discrete entities independent of time. But … a sense of consciousness comes precisely from the flow of perceptions, from the relations among them (both spatial and temporal), from the dynamic but constant relation to them as governed by one unique personal perspective sustained throughout a conscious life; this dynamic sense of consciousness eludes the neuroscientists’ analyses. Compared to it, units of “knowledge” such as we can transmit or record in books or images are but instant snapshots taken in a dynamic flow of uncontainable, unrepeatable, and inexpressible experience. And it is an unwarranted mistake to associate these snapshots with material “stored” in the brain.

This dynamic dimension of consciousness — or what Sarah Manguso has so beautifully termed “ongoingness” — is why our various experiences of time are so integral to our very humanity; it is how we’re able to transmute information into wisdom; it is ultimately what makes us superior to computers. Rosenfield writes:  Conscious perception is temporal: the continuity of consciousness derives from the correspondence which the brain establishes from moment to moment. Without this activity of connecting, we would merely perceive a sequence of unrelated stimuli from moment to unrelated moment, and we would be unable to transform this experience into knowledge and understanding of the world. This is why conscious human knowledge is so different from the “knowledge” that can be stored in a machine or in a computer. Conscious perception is temporal: the continuity of consciousness derives from the correspondence which the brain establishes from moment to moment. Without this activity of connecting, we would merely perceive a sequence of unrelated stimuli from moment to unrelated moment, and we would be unable to transform this experience into knowledge and understanding of the world. This is why conscious human knowledge is so different from the “knowledge” that can be stored in a machine or in a computer.

Illustration from The Book of Memory Gaps by Cecilia Ruiz What powers this continuity of consciousness is memory, that seedbed of our identity, and its dot-connecting capacity (which, lest we forget, is also the seedbed of creativity, perhaps the ultimate faculty that distinguishes us — so far — from machines). Rosenfield explains:  Conscious memory, like all conscious acts, is and has to be relational, and the nature of the relation is different from that in direct perception, although direct perception depends on it. The vital ingredient is self-awareness. My memory emerges from the relation between my body (more specifically, my bodily sensation at a given moment) and my brain’s “image” of my body (an unconscious activity in which the brain creates a constantly changing generalized idea of the body by relating the changes in bodily sensations from moment to moment.) It is this relation that creates a sense of self; over time, my body’s relation to its surroundings becomes even more complex, and, with it, the nature of myself and of my memories of it deepen and widen, too. When I look at myself in a mirror, my recognition of myself is based on a dynamic and complicated awareness of self, a memory-laden sense of who I am. It is not that my memories exist as stored images in my brain, conscious or unconscious; the act of memory is one of my relating to myself, or to others, or to past experiences, or to previously perceived stimuli. This is the very essence of memory: its self-referential base, its self-consciousness, ever evolving and ever changing, intrinsically dynamic and subjective. Indeed, perception in general, conscious awareness of one’s surroundings, is always from a particular point of view, and is only possible when the brain creates a body image, a self, as a frame of reference. Conscious memory, like all conscious acts, is and has to be relational, and the nature of the relation is different from that in direct perception, although direct perception depends on it. The vital ingredient is self-awareness. My memory emerges from the relation between my body (more specifically, my bodily sensation at a given moment) and my brain’s “image” of my body (an unconscious activity in which the brain creates a constantly changing generalized idea of the body by relating the changes in bodily sensations from moment to moment.) It is this relation that creates a sense of self; over time, my body’s relation to its surroundings becomes even more complex, and, with it, the nature of myself and of my memories of it deepen and widen, too. When I look at myself in a mirror, my recognition of myself is based on a dynamic and complicated awareness of self, a memory-laden sense of who I am. It is not that my memories exist as stored images in my brain, conscious or unconscious; the act of memory is one of my relating to myself, or to others, or to past experiences, or to previously perceived stimuli. This is the very essence of memory: its self-referential base, its self-consciousness, ever evolving and ever changing, intrinsically dynamic and subjective. Indeed, perception in general, conscious awareness of one’s surroundings, is always from a particular point of view, and is only possible when the brain creates a body image, a self, as a frame of reference.

This experience of a cohesive self is also why wee are so profoundly disoriented by inner contradiction and conflict. But however trying such dissonance may be to our understanding of ourselves, the very capacity for it is what makes us human:  Confusion and understanding are aspects of conscious behavior, indeed they are states of consciousness, suggesting very different sets of relations between the individual and the world, and there is no way to grasp what they are without some idea of what we mean by consciousness. Computers, for example, which lack consciousness, do not become confused when they arrive at contradictory conclusions or when part of their “memory” is lost; it might also be said that they never “understand” what they are doing. Confusion and understanding are aspects of conscious behavior, indeed they are states of consciousness, suggesting very different sets of relations between the individual and the world, and there is no way to grasp what they are without some idea of what we mean by consciousness. Computers, for example, which lack consciousness, do not become confused when they arrive at contradictory conclusions or when part of their “memory” is lost; it might also be said that they never “understand” what they are doing.

Art by Arthur Rackham from his revolutionary 1907 edition of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland Rosenfield returns to the central role of memory in our sense of understanding — the world as well as ourselves:  Without memory we could never know what we have learned. The problem is that we have tended to think of memories as unconscious items that one brings to consciousness, not as part of consciousness. Without memory we could never know what we have learned. The problem is that we have tended to think of memories as unconscious items that one brings to consciousness, not as part of consciousness.

[…] Nor can we understand the unconscious processes of the brain without understanding consciousness. Our knowledge of the unconscious is derived from observations of conscious behavior, after all. The problem is analogous to the famous discussion in physic as to the nature of light: is it made up of particles or waves? With measuring devices that are sensitive to waves (interference gratings, for example), light manifests itself as waves; with measuring devices sensitive to particles (photoelectric cells), light manifests itself as particles. So is light particle or wave? It is neither; it is simply that we see it as one or the other, depending on the measuring apparatus. So, too, our conscious life suggests that we have memories stored in our brains, but when we try to find where or how they are stored we fail to find the traces of them, and some aspects of our mental life (dreams, for example) suggest that conscious and unconscious forms of memory may be quite different. Actually they are both part of a larger structure, and they manifest themselves in very different ways, depending on our circumstances. An essential part of that larger structure is consciousness.

In the remainder of the thoroughly fascinating The Strange, Familiar, and Forgotten, Rosenfield goes on to explore how phenomena like time, language, and personality elucidate the mysteries of consciousness. Complement it with philosopher Amelie Rorty on the seven layers of identity, naturalist Sy Montgomery on how earth’s most alien creature illuminates the wonders of consciousness, and a beautiful animated short film about memory, inspired by Oliver Sacks. |