In between, however, we often have a memory gap. Events from 5, 10, even 20 years ago slip out of mind but haven’t yet made it into the history books. They can fall into a valley like they never happened. But they did happen, and they matter.

Lately the conversation has been about inflation, a possible recession, and how all this emerged from the pandemic. But it all traces back to events long before COVID. What happened in 2020 certainly changed the timing and some details, but the economy was slowing with an inverted yield curve in 2019.

The events of 2020 were on no one’s dance card and we will debate them for years. Nevertheless, we are still on the road to The Great Reset, just at a faster clip. We can better understand this by recalling the 2008 crisis, the policy responses to it, and decisions made through the 2010s. Today we’ll look at some of that in-between history and how it brought us to this point.

I have been writing for several months about a new research paper (one of my best ever) on energy and a new oil fund that I'm involved with. At the end of this letter there will be a link for accredited investors to see that research and find out more about the fund.

Ed D’Agostino’s One-on-One with Keith Fitz-Gerald:

Stream Before It Comes Offline Sunday In the exclusive interview, Keith answered as many reader questions as he could in the time available. Here’s a brief rundown of the topics and names Keith covered: - Keith described his investing framework in detail, including the tools he uses to weigh one opportunity vs. another.

- He also covered the reason why, among 600,000+ tradable securities worldwide, only 50 truly matter for most portfolios.

- Keith gave his thoughts on Apple, Tesla, Microsoft, Peloton, Goldman Sachs, defense tech names... cybersecurity... AI... and more.

It was a wide-ranging conversation and not one to miss. Click here to stream for free, before it comes offline Sunday.

(From our partners.) |

If you like social media memes, you’ve likely seen examples of “How It Started/How It’s Going.” Basically, this is where you show two pictures of the same person, first very sure of themselves, and then amid embarrassment or disaster.

These are amusing because we savor that schadenfreude feeling, but the memes make a good point, too: The line between confidence and arrogance, between intentions and results, can be a lot thinner than we think.

But there’s also a wrinkle to this: Often people try to appear confident even when they aren’t. Central bankers, for example, always have “credibility” in mind. In a fractional-reserve banking system, people must believe the lender of last resort is trustworthy. Maintaining that confidence is always the top priority.

Yet the reality in crisis periods is the Federal Reserve simply doesn’t know if its plans will work. No matter; they’re still unveiled with great confidence, which continues until they fail. Then the next plan is unveiled with equally great confidence, and the next, and the next.

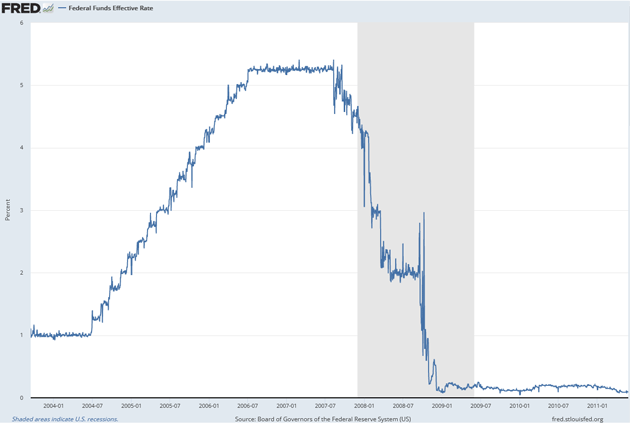

Something like that happened in the Great Recession. We forget today exactly how that period unfolded, so let’s review the sequence. We can do this visually by following changes in the federal funds rate. Here it is from 2004 through 2010.

Source: FRED

The expansion period began with the Fed holding its main policy rate at 1%, where it had bottomed after the previous cycle. By summer of 2004 the Fed thought it was time to raise rates, and it did so steadily for the next two years. Whether that tempered growth is still unclear. It may be that the prospect of higher rates made people even more eager to buy homes (and lenders more eager to finance them) before rates rose further.

Regardless, in late 2007 it was pretty clear something was amiss. Deals were blowing up, fund managers running into trouble, etc. Not seriously so, but enough to warrant a response. So began the rate cuts. Then in 2008 Bear Stearns imploded, followed months later by Lehman Brothers.

At every step along the way, Fed officials thought (as did many analysts) they had the situation under control. (“Subprime is contained.”) The good times would resume shortly. They did not.

In late 2008 fed funds was approaching zero and people were asking, quite reasonably, what the Fed would do next. At the time, the “QE” (quantitative easing) that is now so familiar to us was just an obscure academic concept. It became more than academic in November 2008 when the Fed announced it would purchase $600 billion in agency mortgage-backed securities (Fannie Mae, etc.) and associated debt. This, combined with the zero-bound fed funds rate reached the following month, was to be the solution.

(For the record, I was against taking rates to zero, let alone leaving them there. But I did agree with QE1, just not subsequent monetary expansions. Don’t even get me started on the bank bailouts, but in the middle of a crisis no one had a playbook for a liquidity crisis in the US. They made decisions because they had to.)

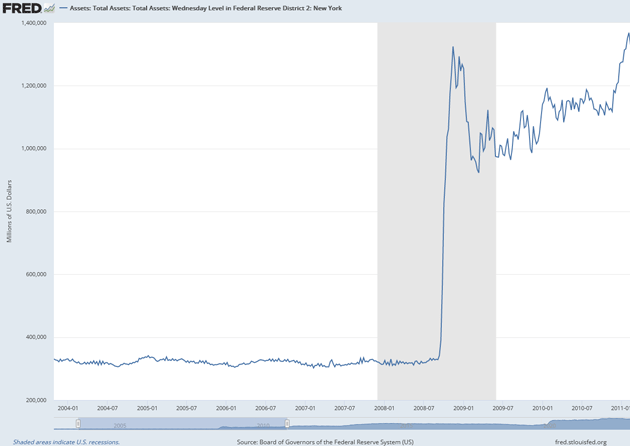

This chart is the Fed’s balance sheet assets for the same period as the rate chart above.

Source: FRED

Fed assets held steady at a kind of housekeeping level for years before going vertical at the end of 2008. And then something critical: A quick attempt to shrink the balance sheet a couple of months later ran into a brick wall. Free money turned out to be pretty popular.

In March 2009 the Fed expanded its MBS purchase program and added Treasury bond purchases as well. They initially framed these as temporary, with end dates and limited amounts. Very soon, though, it was clear those limits were just words. The Fed was trapped and would keep stimulating indefinitely.

That realization changed everything. It took the Fed from “How It Started” to “How It’s Going,” and set in motion a process that put us where we are today. It is not coincidence a massive bull market in stocks began in March 2009. Liquidity matters.

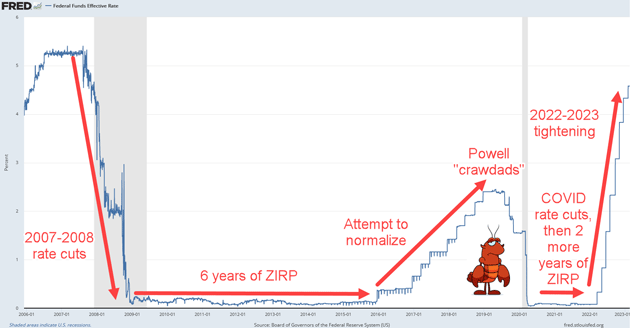

Now let’s bring that data forward with a couple more charts: the same data, just brought up to date. Here is fed funds from 2006 to the present, with a few annotations.

Source: FRED

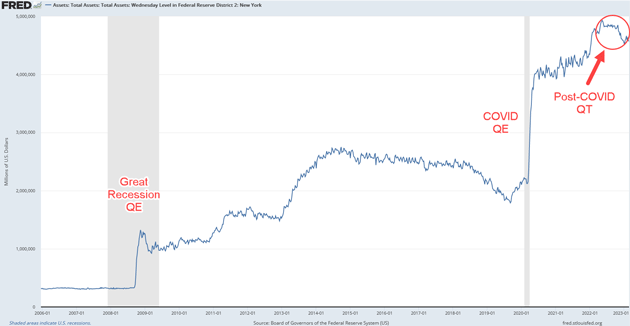

And here are Fed balance sheet assets for the same period.

Source: FRED

What looked like—and was—aggressive, unprecedented intervention in 2008‒2009 was quite mild compared to what followed. Six more years of zero rates and vast asset purchases, a half-hearted attempt to normalize before Jerome Powell “crawdadded,” (walked backwards) as I called his seeming surrender to markets at the time. Then two more years of ZIRP after COVID struck and now a rate “normalization” that still hasn’t reached what was “normal” in 2007, and “quantitative tightening” that has yet to make a significant dent in the balance sheet.

Put all that together and you begin to see why the current tightening cycle upsets so many investors. Until last year, many knew nothing but zero or very low rates and a stock market with highly favorable tailwinds. Even some graybeards let hope get the best of them, thinking it really was different this time.

But the years of easy money didn’t just boost markets. They changed the economy itself.

Charles Gave often observes how low interest rates change the way borrowers behave. When capital is expensive, they borrow to build new productive assets that will (they hope) generate self-sustaining cash flow. They open businesses, build factories, develop innovative new products and so on. This adds up to GDP growth.

Conversely, cheap capital—the kind artificially low interest rates provide—incentivizes the use of borrowed money to buy existing assets, not new ones. That’s not necessarily bad but it has different macro effects. Instead of GDP growth, it raises the price of the assets people are competing to buy. Shares of stock are the best example. Unless it’s an IPO or other new offering, most stock investment doesn’t go to the company. It goes to some other shareholder, who naturally wants to get the highest price possible—as will you once you own that share. All good but it doesn’t create any new productive capacity for the economy.

The same applies to companies. Rather than reinvest profits to grow the business, low interest rates make it more attractive to buy their competitors, or use borrowed cash to buy back their own shares. This, again, means lower investment in new capacity and increased industry concentration. With less competitive pressure, product quality and customer service can deteriorate even as prices rise.

My friend Lance Roberts recently surfaced an old Jeremy Grantham quote I’d forgotten:

“Profit margins are probably the most mean-reverting series in finance. And if profit margins do not mean-revert, then something has gone badly wrong with capitalism.”

For the record, I fully favor both capitalism and profits. The point here is that profits have an economic function. High profit margins signal opportunity exists in this sector or place, thereby drawing competitors to offer better products and prices. Consumers (i.e., all of us) enjoy the benefit. That’s how capitalism should work but recently hasn’t.

The easy-money era sent the wrong signals to politicians, too, making debt temporarily less daunting and encouraging all kinds of wasteful spending. Worse, government at all levels didn’t do what would have made perfect sense: use low long-term rates to finance much-needed infrastructure repairs and improvements. So now we are stuck with substandard roads, bridges, utilities, and other growth-inhibiting messes.

Now add to this the other inflation pressure that grew out of COVID—supply chain snafus, travel restrictions, etc.—and the demographically-driven labor shortage. The inflation we see now makes perfect sense. The Fed and other central banks didn’t cause the pandemic, but they established the conditions that let it have these effects.

Worst of all, this “financial repression” favored investors but also punished savers. Not so long ago one could accumulate a nest egg, invest it in simple, low-risk bonds and generate good income. That became impossible under ZIRP and still is today since inflation has overwhelmed the benefit of higher yields. It’s left many retirees in desperate positions, and it wasn’t an accident. It was a planned, intentional policy that started badly and only got worse.

In the late 1970s, there was a classic commercial about Chiffon margarine fooling Mother Nature. It ended with, “It’s not nice to fool Mother Nature.” But that's exactly what the Federal Reserve has done since Greenspan. Let's detail the ways:

With a few exceptions, Greenspan left well enough alone in the ’90s. The dot-com mania was a “madness of crowds” event. An unrelenting 18-year bull market ended in a crash. And the Greenspan Fed did the theretofore unthinkable, taking rates to 1%. Greenspan explicitly targeted stock market returns. The markets, used to the “Greenspan Put,” rejoiced. And low rates, thought to boost the economy, had a perverse effect. The economy recovered but the economic and business game changed.

Source: FRED

As noted above, messing with market rates distorts economic incentives. The driving force in capitalism has always been to maximize profits. With low rates, buying your competition rather than competing against them became the easier way to maximize profits. That short-circuited Schumpeter’s creative destruction, a necessary if messy component of true capitalism, and reduced GDP growth. We clearly slapped Adam Smith’s invisible hand away from the playing table and instead let 12 people sitting around a table decide the world’s most important price: the price of money.

Low interest rates starve retirees and investors of reasonable returns. When rates are at zero investors are forced to take more risk at precisely the time they should be getting more conservative.

Powell was not truly free to raise rates until his second term was confirmed on May 12, 2022—not if he wanted to get confirmed. Inflation had already begun to ramp up and the Fed was way behind the curve. With the Federal Reserve keeping rates at zero too long and doing too much QE, combined with the massive over-stimulus of the economy by Congress, we are dealing with inflation that should not have been. But it is.

I know many feel the Fed should at a minimum pause the rate hikes and maybe even cut rates. The 20+-year addiction to low rates has distorted behaviors to the point that once-normal rates are difficult for many companies and private funds to manage.

I am perfectly comfortable with 5% interest rates when inflation is 4‒5%. I hope rates stay high enough to give investors a real return on their savings, and less incentive to buy your competition rather than actually invest and compete.

I truly hope we never once again feel that we have to get inflation to 2% because it is “only” 1.8%! What were we thinking? What is magic about 2% inflation? Inflation is destructive at any level.

Former BIS chief economist William White sent me this note as we were discussing the topic yesterday. It is from one of his essay’s quoting Paul Volcker’s autobiography in 2018.

“Whatever the motivation, the undesirable side effects of ultra-low rates are now being encouraged still further. The dangers arising from this policy were well summarized by the late Paul Volcker in his recent autobiography. He said ‘Ironically, the ‘easy money’ striving for a ‘little’ inflation as a means of forestalling deflation, could, in the end, be what brings it about.’”

It's not nice to fool around with market incentives. That Chiffon margarine commercial ended with an angry Mother Nature creating a thunderstorm. What kind of economic weather will we get from distorting the incentives of the free market?

I have become increasingly convinced that the ESG movement, by trying to restrict investments in oil and gas ventures, is going to have the perverse effect of reducing supply even as global demand increases, thus making the price of energy rise. It is simply not rational for the developed world to expect developing countries to ignore the needs of their citizens to have access to power and clean water which requires energy, and specifically oil and gas (and to some extent coal).

History clearly shows that the increased use of energy (of all types) is what drives the economics, health, and prosperity of humanity. The data on supply and demand for oil and gas is compelling. Once again, this year will be an all-time high in demand for oil and gas, a trend that has only been interrupted during recessions over the last century before quickly recovering to new all-time demand highs. I am bullish over the medium- and long-term prospects for oil and gas prices. The chart below shows that we are going to need to drill a lot of wells just to stay in place, let alone meet increased demand.

Source: Bloomberg

The question is: “What is the best way to take advantage of this misguided policy?”

Bottom line: One potentially significant upside in oil and gas investing is not just the actual price of oil and gas (which is important!), but the increase in the value of proven and probable reserves in the field. Think of it as buying an older apartment complex in a good neighborhood, doing a complete renovation, increasing the price of the rent and then selling the complex at the new increased value. Essentially, what my partners at King Operating do is buy the rights to drill in an older but proven field in a “great neighborhood.” Typically, the older fields were all vertical wells, but you can improve the value of that old field by doing horizontal drilling and fracking. (Oil and gas is a risky business and past performance is not indicative of future results.) It's more complex than that, but that is the essence.

My partners at King Operating have helped pioneer this investment model (wells plus the field) for retail investors. I have written the first of what will be a series of research papers on energy, that also outline the strategy. I think it is some of the best research and writing I have done in years. I really hope you read it. Due to regulations, this offer is limited to accredited investors. If you would like your copy of my report, click on the link below at the end of the following disclosure.

Important disclosures: Note that John Mauldin’s association with King Operating is completely separate, legally and financially, from his involvement with Mauldin Economics. The opportunity presented above by John Mauldin in TFTF is not endorsed by Mauldin Economics, ME Research LLC, or any of its other partners nor do any of them have any financial or other interest in the described venture.

John Mauldin will be receiving significant financial benefits from investments made in this venture by investors. More specifically, as chief economist of King Operating, John is entitled to receive consulting fees as well as a significant interest in the fund’s general partner.

This opportunity is offered by King Operating and it is limited to accredited investors. Prospective investors should carefully review the offering memorandum and risks disclosure before proceeding.

Click here to download my report The Future of Energy on King Operating’s website and find out more.

I am actively working on getting to Austin for both business and personal reasons. I have so many friends I want to catch up with and need to do a client meeting. Looks like a second visit to Austin may be shaping up in late April. I still need to get to NYC and Dallas again.

I am really focusing on the SIC and must admit it is fun in an age of Zoom to get to talk with so many creative people. This will be the best SIC ever.

And once again, in case you've missed it thus far, I direct your attention to the conversation between Keith Fitz-Gerald and Ed D'Agostino. Keith dives deep on his approach to choppy markets, diversification, what the Fed could do next, and a variety of other topics. Keith tells me the video and special price for my readers won't be available beyond this weekend, so please watch (or read the transcript) by clicking here.

And with that, it’s time to hit the send button. Have a great week and don’t forget to follow me on Twitter! And make sure you get your copy of that energy report. I think you will enjoy it.

Your back to his oil roots analyst,