Pandemonium broke out in Africa. The software developers working for a New York startup headed toward a billion-dollar valuation were angry. Their company, established to help the African continent by training computer engineers and outsourcing them, was just featured in an article they felt significantly overstated their wages. They wanted the world to know they made far less. They wanted a correction.

“Frankly I’m disturbed,” one Nigerian developer said in a companywide chat on Slack. “What does this say about our very own integrity?”

“The partner thinks we earn way more than we actually do,” said another.

The company, Andela, is a darling of venture capitalists interested in social good. It’s raised $181 million with a straightforward message: “Brilliance is evenly distributed, but opportunity is not.” Al Gore, Serena Williams, Mark Zuckerberg and Pricilla Chan have all invested in Andela. Zuckerberg and Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey have posted smiling photos from its offices in Africa. Yet life inside Andela isn’t as ideal as the wide smiles, money, and press releases would have you imagine.

|

The uprising over pay inside Andela — among dozens of internal messages and documents Big Technology obtained, along with more than 15 interviews of current and ex-employees — is but one example of how the socially-minded enterprise has struggled to deliver on its promise. Many people in Andela’s orbit feel it’s a net positive for the countries it operates in. Yet its strategy misfires and communication blunders have left its African developers in a lurch, underscoring how difficult blending capitalism and social good can be. Stung by the experience, some developers informally refer to the company as “The Plantation.”

“You feel exploited,” one current Andela developer told Big Technology. “You work so much. No one really cares.”

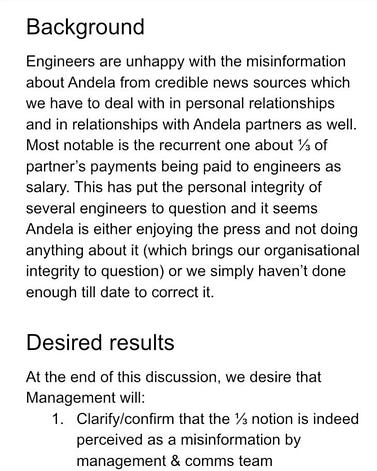

At issue in the pay dispute, which took place last summer, was a BBC article claiming the company’s developers earned one-third of what international clients paid for their time. The fraction, though small, exaggerated what the developers were taking home, they felt. Andela’s public statements forced them to explain to clients and family that they weren’t actually wealthy, they said. The protest wasn’t without merit.

“The one third is fictitious,” Andela CEO Jeremy Johnson told Big Technology in a candid interview last week. Some developers make less than a third of what clients pay, some make more, varying by country and seniority level. But the number never accurately described how Andela compensates its developers. “We absolutely bear responsibility for the miscommunication,” Johnson said. “Without question.”

Money and Misfires

In 2014, Johnson, Nigerian entrepreneur Iyinoluwa Aboyeji, and a cadre of others founded Andela to “empower young Africans to take back the continent through education,” according to a post by Aboyeji. Their plan was to recruit brilliant Africans, promise them economic opportunity, and teach them to code. They’d place these newly minted engineers at international companies seeking software developers amid a talent shortage.

“Even as young people in Kenya, Nigeria, and so many other countries are looking for work, tech companies around the world are having a hard time finding talent,” Johnson wrote in 2014. “The digital revolution may have started in Palo Alto, but its future will be written in Lagos, Nairobi, and Accra.”

Young Africans took to Andela’s message. More than 5,200 applied for the first 28 spots, and the company boasted about it. “That’s an acceptance rate of .53%,” Johnson said at the time. “We’re already ten times more selective than Harvard.”

Andela paid its developers as they trained, and it continued to pay them as they sat on “The Bench” waiting for Andela to place them with a client.

“Andela was the hallmark,” one ex-Andela developer told Big Technology. “It was seen as the place every developer should aspire to work in.”

Andela succeeded early on, placing developers at prominent US tech companies including Udacity and Microsoft by 2015. That summer, it raised more than $10 million in venture funding. And then the VC money kept pouring in.

Andela raised $24 million in 2016, $40 million in 2017, and $100 million in January 2019. It followed a common startup strategy: Get big, and do it fast. “In 2019, Andela is projected to double in size, hiring another one thousand software developers and investing heavily in data, engineering, and product development,” Al Gore’s Generation Investment Management said as it announced the $100 million round.

But just as Andela was hitting its stride, its master plan started breaking apart. Coding bootcamps in the US scaled up fast and began training ambitious professionals seeking to break into software development — competing directly with Andela. Computer science programs in universities ramped up as well, putting more talent on the market.

When the software developer supply rose faster than Andela anticipated, the company’s “bench” filled with junior developers it couldn’t place with clients. And there they sat.

|

“I probably wouldn't have been crazy to imagine that bootcamps would have grown like that. That was our trend in 2014,” Johnson said. “But with General Assembly and a couple others — it was still relatively small. It would have been hard to imagine that pace of growth.”

For Andela’s developers, sitting on the bench was miserable. They got paid, but they didn’t get meaningful client experience, struggled to advance inside the company, and feared for their jobs, according to multiple developers Big Technology interviewed. Some left higher-paying jobs to join Andela and grew frustrated when the promise didn’t materialize.

“I resigned where I was working, just to work with American or European companies,” one ex-Andela developer said. “I was feeling anxiety, I was feeling depressed, and that was not easy for me. I'm glad that I was able to get out.”

The growing bench also depressed the wages Andela paid to those developers actually working with clients. “How could it not?” Johnson said, confirming this. “As a company we've cut costs a couple times over the past year. Our burn is down, but we're not profitable. Obviously there's a finite spend that you can have as a company. It certainly impacts wages.” Johnson said the company spent 80% of its revenue in 2019 to pay or support developers.

As Andela moved into 2019, many within the company felt the mood shift. It moved from something resembling an NGO to a profit-driven enterprise — which it indeed always was. Internally, there was also a recognition that its original plan had failed. Training Africans with little technical experience and placing them at international companies wasn’t going to be viable, at least not viable enough to justify $181 million in funding.

“The more money you raise, the more revenue people expect,” one former Andela employee told Big Technology. “There was beginning to be a shift away from mission to become primarily driven by revenue.”

To keep Andela on track, the company accelerated its hiring of senior developers. These more-skilled developers could easily get client work given their in-demand skills, and Andela could put them to work much faster. Hiring senior developers frustrated junior developers, who were typically paid less after months of training.

Tensions were high when the BBC published an article in August 2019 headlined: Engineered in Africa: 'We knew the talent was there’. The story — which included the line about developers earning one-third of what clients paid — did not resonate with Andela’s developers, many of whom were on the bench or getting paid less than they wanted. Their frustration poured out in Andela’s #General Slack channel.

“I would like to know, did Andela at any point in time tell any news source we get one third?” said one developer. “This info has been flying around for a long time and it does not seem to bother Andela.”

Andela’s engineers then sent a document to management, calling out the company’s public statements on their pay — versions of which also appeared in Techcrunch and Forbes — and asking it to confirm it was “misinformation.”

|

The numbers were “causing the world to have unfounded beliefs about how well-off Andelans are,” the document said. “This then leads to interpersonal friction when the Andelan says he/she isn’t as affluent.”

Company leadership responded in Slack. “For many folks, it’s a bit frustrating that after 5 years, the media still doesn’t verify certain things about Andela or they just copy/paste content that’s outdated or obsolete.” It suggested developers “tread carefully with those friends & ‘associates’ who read this article and now think we’re all billionaires looking to give them some free money.”

The BBC did not correct the article.

Andela then began to clear the bench, laying off 400 junior engineers in October 2019, just two months after the Slack uprising. “We’ve seen shifts in the market and what our customers are looking for…toward more experienced engineers,” Johnson told Techcrunch.

The confluence of layoffs, pay disputes, and long waits on the bench caused the environment inside the company to deteriorate, according to multiple Andela developers. “The decisions were just made in a rush. No one knew about them,” one current Andela engineer told Big Technology. “So it sounded like we’re being isolated and you're just there to work and go home.”

A group of former and current developers started an unsanctioned Slack to blow off steam. In this Slack, some developers casually referred to Andela as “Plantation,” according to four current and former employees and screenshots Big Technology reviewed.

“The plantation one hurts,” Johnson said. “That I hadn't heard. People feeling they wanted to be paid more, of course.”

Some Andela employees left the company wondering whether the private sector, and VC funded companies in particular, were well suited to tackle big geopolitical problems. “Coming out of Andela, I have gone through a professional crisis, thinking — Is the entire venture capital business a sorry excuse for us saving or reinventing other institutions?” one ex-Andela employee told Big Technology. “Why is it the private sector that needs to come in and innovate? Why can't schools, governments, etc, do that job?”

But though its impact has been complicated, Andela has done real good for the countries it operates in, and for many of the people it’s employed. Andela has paid for developer training with no guarantee of a return, it’s elevated the reputation of African software developers, and it’s helped lift up the tech scene in the countries it operates in. “They open their offices to so many learners, and WordPress meetup groups — they do so much to catalyze the local economy from a pure infrastructure standpoint,” said the same ex-employee. “That's an unsung part of their business.”

Oo Nwoye, a Nigerian tech entrepreneur, said that Andela has been a net good for the country, putting the Nigerian tech scene, and the talent within it, on the map internationally. “Before now, the idea of Nigerian developers being looked at all, it was far fetched,” he said. “It actually opened the market for us.”

Where To Next?

As the reporting for this story neared completion, an Andela PR representative called. Andela had caught wind of LinkedIn messages flooding its employees’ inboxes and wanted to talk. The communication representative arranged the interview with Johnson.

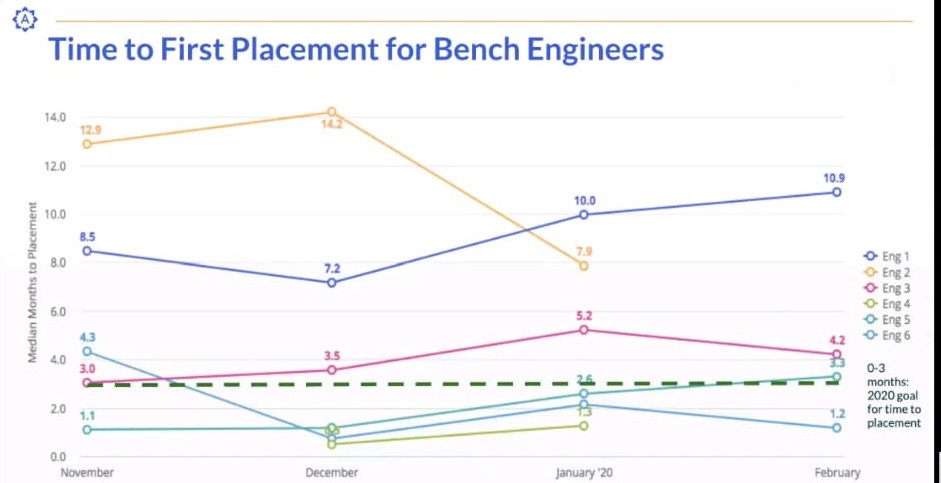

For Andela, 2020 has been a tough year, as it has for many companies. Andela began the year planning to further reduce its bench. An internal presentation showed 198 engineers in Andela’s junior levels had been on the bench for more than three months. Its most junior engineers were on the bench for an average of 10.9 months. Andela asked many to leave voluntarily. And in May, Andela further laid off 135 employees and moved its offices remote.

In the interview, Johnson spoke hopefully of the company’s future, explaining how it was expanding a “network” of developers who could work with Andela’s clients even if they weren’t full-time employees. “The idea is that you'd be able to expand the number of opportunities you could create by also expanding the pool of talent that you have on the demand side,” Johnson said.

The network, Johnson explained, would make opportunities available to developers across Africa. Andela previously limited these jobs to countries including Nigeria, Kenya, Rwanda, and Uganda. Now, the entire continent could apply.

Andela’s planned expansion evoked a question many in the company’s orbit wondered aloud: Would Andela eventually expand outside of Africa? “Definitely,” Johnson said. “Ten years from now, we’re probably on every continent.”

You’re reading Big Technology from Alex Kantrowitz. Check out what this publication is all about here. Pick up a copy of Alex’s book, Always Day One, here.