|  Dear Reader,

I’m sure that you have seen the images and videos from last week, when protestors packed into the Capitol to demand an end to social and business restrictions ordered by Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer.

Some of you were disturbed by the display of assault weapons, Confederate flags and even swastikas, or by the jostling and shouting outside lawmakers’ chambers. Regardless, those citizens were exercising their First Amendment rights.

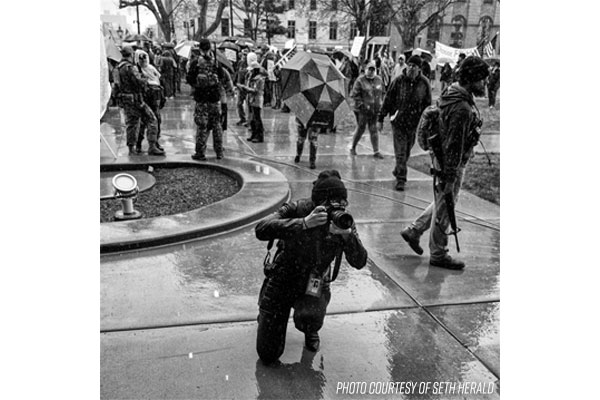

So were we. MLive.com had three journalists in the thick of protest – reporter Matt Durr, photographer Nicole Hester, and videographer Neil Blake. Their work provided vital in-the-moment news coverage for you, and also captured the event as a form of documentary of an unprecedented era.

I began to write about why this matters. About the occupational perils that journalists accept as part of their calling. About the decisions these professionals make, on the fly and under duress, to ensure context and balance in their work.

But once I interviewed our journalists, I felt their words – and commitment – were more powerful. So this is their story. It centers on one intense news event, but it really represents what all MLive journalists bring to stories every day, all across Michigan.

Q: What was it like among the crowd? What was the mood?

Matt Durr: The majority of the anger was directed at the governor and the people inside the Capitol. I did encounter two women who made it a point to tell me off. One woman told me I asked stupid questions because everyone already knows why people are protesting. Another asked if I worked for MLive. When I replied “Yes,” she told me I should be ashamed of myself because, “People like you are killing more people than this virus.”

Nicole Hester: (It was) chaotic and intense. A few people apologized and told me they didn’t mean to be bumping into me but there was no room, others mocked me for wearing a mask. It was a mix of people and beliefs, as these things often are.

Neil Blake: In front of the steps where the speakers were, people were standing close together. While many people were angry with the way Gov. Whitmer has handled the crisis, the mood in the crowd was upbeat and enthusiastic. Worship music was being played and I heard some “Don’t Stop Believing,” by Journey, at some point.

Q: Were there any specific threats directed at you? Did anyone try to stop you from doing your job?

Hester: There always is (a threat). I’ve had people threaten to kill me, or arrest me, and as a woman … I’ve been grabbed and made the object of someone’s inappropriate joke. I’ve fought people off of me. So some guy with an iPhone calling me “fake news” doesn’t faze me anymore. I’m not there to debate them, I’m there to document what is going on.

Durr: With dozens of people walking around with guns hanging across their body, all it takes is one person to turn the whole thing into a nightmare. And that’s aside from the angry people who don’t like or trust the media and are willing to tell us off.

Hester: Events like this, people need to understand you are in a public space and we are protected by the Constitution to do our jobs, and that’s what we are there to do. If you don’t want to be photographed, don’t go.

Durr: For the most part, the people I spoke with were thoughtful in their concerns, acknowledged that there’s blame to go around, and had legitimate arguments. Even though the national headlines, photos and videos ended up focusing on the situation that unfolded inside the Capitol, it’s not fair to paint everyone who was there as a radical, gun-toting extremist who was acting irrationally. People have a right to peacefully protest, and whether or not you agree with their points, I felt like it was my job to report on how I experienced the protest.

Q: How do you find a way to cut through the spectacle of it to get the substance of the story, provide balance and context?

Hester: You have to keep asking, “What is the story?” and remember to think beyond event coverage. Asking what is happening in front of you that maybe isn’t as loud or not as obvious.

Blake: This is something I think about constantly on assignment. I know that the photos or video I take can greatly impact how people see the protest. Standalone images (are) not the complete story, as the majority of protesters were abiding by social distancing. I tried to give our readers an accurate account of what happened. That’s one reason I think using Facebook Live in our reporting is important. It lets our readers see in the moment what’s going on.

Q: How aware were you of personal safety, from the perspective of the coronavirus?

Hester: There was no way to practice social distancing and document what was going on inside the Capitol up close. But what happens if we don’t show this happening? If there are no photos no reporters – there is risk in that. Every one of my colleagues is taking this pandemic seriously, but we also realize the value in what we do.

Blake: I was concerned about exposing myself to the coronavirus. I was constantly aware of my surroundings and how close people were getting to me. A few protesters wore masks, but the majority did not. I consciously chose to take on some risk to get the video footage of the protesters yelling at the troopers, because I felt it was important to the story and for people to see.

Durr: The stress of a situation like this doesn’t end when the protest ends. Because I didn’t paint the entire crowd with a broad brush, I’ve received several angry emails from people who disagreed with the protest. I was accused of being a white supremacist and a racist.

Hester: How I feel is: This is what I feel I signed up for. I knew photojournalism was a lifestyle and there is risk in that.

I am proud of, but not surprised by, the commitment this trio showed on this assignment. Across the state, throughout the year, MLive journalists wade into all kinds of situations to get the news, at the source, and relate it to you with professional-grade accuracy and balance.

Nicole Hester said it best: It’s what we signed up for.

|