Money supply spike: Sources and implications

Money supply in the U.S. has spiked at an unprecedented rate. M2 rose 3.8% in March, 6.7% in April, and 5.0% in May, a stunning 83% annualized growth rate for the three months. This lifted the year-over-year growth rate of M2 to 23%, almost double its prior fastest rate in the modern era. The money stock has also increased rapidly in other nations. Traditionally, rapid money growth would point to booming economic growth and soaring inflation. We know that the Federal Reserve is aggressively easing monetary policy. What are the sources and implications of this surge in money in the U.S.? The recent surge in the money stock is much more complex (and interesting) than simply attributing it to the expansive policies of the Federal Reserve, and using historic (and dated) rules of thumb to say it will generate booming economic growth and high inflation is overly simplistic and very likely incorrect.Â

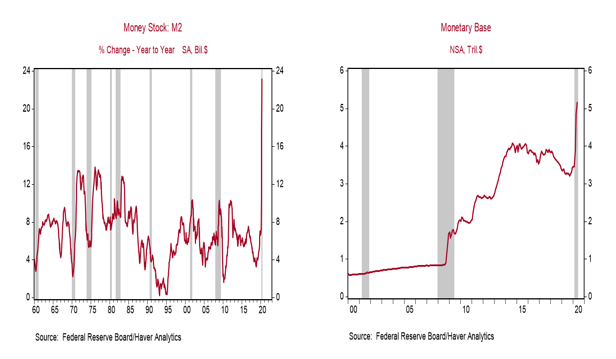

Chart 1Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Chart 2

While the Fed is pursuing very aggressive monetary easing, the recent surge in money supply since March reflects risk aversion and the impact of the U.S. government’s fiscal initiatives more so than monetary policy. Unquestionably, the Fed is pursuing unprecedented monetary easing. Its quantitative easing—massive purchases of Treasuries and MBS that have ballooned the Fed’s balance sheet from $4.1 trillion in February to over $7 trillion presently— has boosted the monetary base (MB), which comprise bank reserves plus currency by over $2 trillion (Chart 2). The Fed’s emergency lender of last resort facilities, including providing liquidity to short-term funding markets, purchases of corporate bonds and municipal debt, and its direct business lending, have flooded financial markets with liquidity and added to its balance sheet. M1 money supply includes currency and demand and other checkable deposits, while M2 also includes non-transactions components such as savings deposits, small-denomination time deposits, and retail money funds. Unlike the Fed’s quantitative easing following the financial crisis of 2008-2009, which boosted the monetary base but did not materially affect the broader money stock, the Fed’s recent balance sheet expansion has been accompanied by a significant increase in M2. Â

Bank deposits, the primary component of the money stock, have spiked as a result of cash hoarding by risk averse businesses and households, plus the U.S. government’s fiscal programs that have provided over $400 billion in income support to individuals and hundreds of billions of loans and grants to businesses that have boosted deposits in their bank accounts.Â

As the economy reopens and confidence lifts, households will spend some of their deposits, boosting consumption, and firms will reduce their deposits to finance basic business operations and pay down lines of bank credit. The spikes in M1 and M2 will reverse. The level of economic activity will rise. The simple assessment that the rise in money will lead to a pickup in growth will be right in direction. But even if there is a powerful V-shaped recovery, the naïve monetarist view will be completely wrong in the magnitude of the correlation between money growth and real economic growth, and most likely will vastly overstate the inflationary consequence of the surge in M2. The risks of undesired high inflation would materialize only if the high-powered money created by the Fed generates a sustained acceleration in economic activity that results in excess demand relative to productive capacity. This risk must be closely monitored but is inappropriate to include in a baseline forecast.

Sources of the spike in money supply

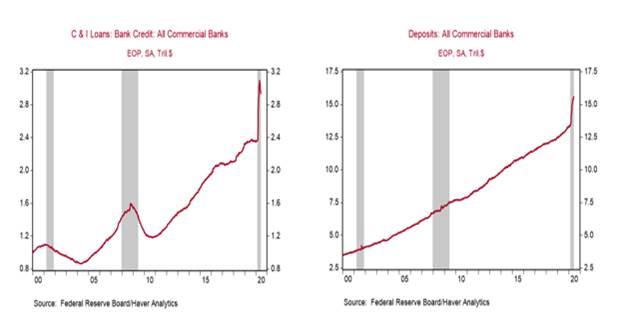

In early March, businesses shifted toward extreme risk aversion in anticipation of the spreading pandemic and government shutdowns that would halt their cash flows. Many businesses were also concerned that their banks would cut their lines of credit. They drew down their unused lines of credit and left most of the proceeds in their bank accounts. According to official data that the Fed collects from commercial banks, commercial and industrial (C&I) loans rose 9.3% in March, by far its largest in history (Chart 3), and simultaneously, bank deposits also experienced the largest monthly increase ever (Chart 4). Risk averse households added to the surge in measured deposits as they reduced exposure in the reeling stock market, which declined 19% in March, and raised cash. Demand and other checkable deposits rose 10.4% in March, while savings deposits (including MMDAs) rose 2.8% in March. These percentage increases were “off the charts” relative to their historic patterns. Mirroring these spikes, M1 rose 6.4% in March, while M2 rose 3.8%.Â

Chart 3Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Chart 4

The even larger spikes in bank deposits and money supply that occurred in April and sustained in May were fiscal policy related. The CARES Act, enacted March 27, provided $1200 to individuals ($2400 to couples) and $500 to children. The payments phased out for individuals and couples with adjusted gross incomes of more than $75k and $150k, respectively, up to $99k and $198k. According to the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA), the CARES Act provided $300 billion in direct payments to individuals. The government distributed the one-time income support checks in April and May. In addition, the CARES Act enhanced unemployment compensation by an additional $600 per week and extended the program to millions of independent workers (contract workers) who traditionally had not been eligible. The dramatic increase in enhanced unemployment compensation payments mounted in April and May with the surging ranks of unemployed. The BEA estimates $144 billion in payments related to unemployment compensation in those two months.Â

While cash-constrained recipients cashed the checks they received from the government and spent the proceeds immediately on essentials, a large share was deposited in bank and credit union accounts. These deposits, plus sizable (but not dramatic) increases in currency, are reflected in the monetary aggregates as very large monthly increases in M2 of 6.7% in April and 5.0% in May.

The implications for the economy and inflation

The economic recovery reflects primarily the ending of the government shutdown and ebbing of the pandemic. Of course, aggressive monetary and fiscal policies (including the Fed’s direct business lending programs conducted on behalf of the Treasury and Congress) are influencing economic activity, but a critical determinant of the pace of recovery is household and business confidence in health and medical issues related to the pandemic.  Â

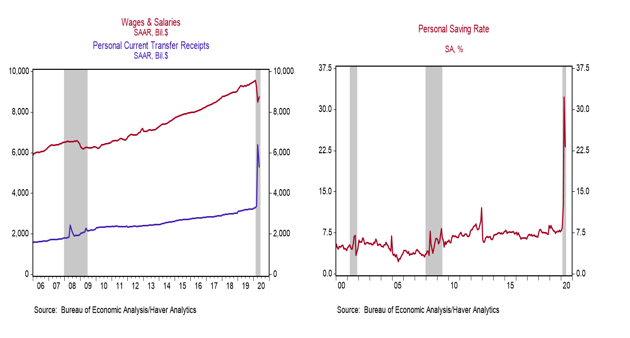

It is striking that during a period of the fastest rise in unemployment in U.S. history, while wage and salary income plummeted a cumulative 8.6% in March-May, a whopping 30.2% annualized decline, disposable incomes actually rose, reflecting the surge in government transfer payments (Chart 5). With consumption constrained by the government shutdowns and caution about the pandemic, personal saving surged to $6 trillion annualized, and the rate of personal saving (the change in disposable income less consumption) jumped 12.6% in March, 32.2% in April, and remained elevated at 23.2% in May (Chart 6). Both the level and rate of personal saving rose to their highest values in history. This suggests that consumers have a sizable amount of pent up demand for goods and services. In addition, the Fed’s low interest rates and bond purchases have lowered mortgage rates and stimulated housing.Â

Chart 5Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Chart 6

The bulge in money supply will eventually unwind as businesses reduce their C&I loans and deposits, households spend a portion of their deposited savings, and the government unwinds portions of its generous income support programs. This unwind of the money growth will unfold even as the Fed extends its aggressive monetary easing.

As evidenced by the decline in C&I loans in the last four weeks as shown in Chart 3, businesses have already begun to pay down their lines of credit, reducing their bank deposits. C&I loans typically decline during recessions and early stages of recovery, and this pattern seems likely to hold in the current cycle. To date, the decline in business deposits have been more than offset by increases in consumer deposits, reflecting ongoing government income support payments to individuals. The government’s enhanced unemployment compensation is scheduled to expire at the end of July. While we expect the basic unemployment insurance program to be extended, the status of the enhanced amounts is uncertain, and this will affect bank deposits and the money stock. Â

The spike in M2 does not imply a surge in inflation, unless there is a sustained surge in aggregate demand, but combined with the unprecedented increase in deficit spending aimed at stimulating the economy, the risks of inflation are material and should be closely monitored. While the sharp economic contraction in the first half of 2020 has involved insufficient aggregate demand and downward pressure on prices, a sustained rapid growth in nominal GDP would generate excess demand and inflation. That would require that the high-powered money that the Fed is pumping into financial markets is put to work in the real economy. The sustained low inflation since the financial crisis of 2008-2009 occurred because the Fed’s aggressive QE during the economic expansion resulted in excess reserves in the banking system and did not generate a sustained acceleration in nominal GDP. This time may be different: the combination of reopening the economy and unprecedented expansive monetary and fiscal policies may be a formula for generating excess demand and high inflation.

Mickey Levy, mickey.levy@berenberg-us.com