Rising inflation: granular data analysis shows broadening dispersion of price increases

*We analyze price movements of over 200 components of the Consumer Price Index during different periods in time.

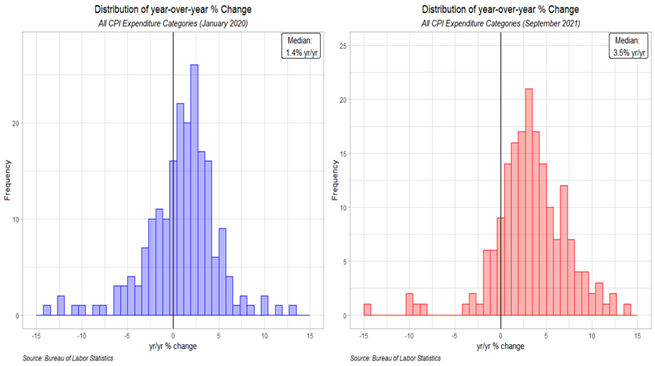

*The year-over-year price changes of detailed components of the CPI show a clear acceleration of inflation across a wide array of goods and services (Chart 1). The portion of CPI components that are experiencing yr/yr price increases exceeding 3% has more than doubled from before the pandemic, and the portions of components experiencing yr/yr price increases above either 6% or 10% are five times higher than before the pandemic.

*These findings of widespread acceleration of inflation, along with other research on the PCE price index, refute the Fed’s assertion that the rise in inflation has been driven by a narrow group of items. The implications are important for the thrust of inflation and inflationary expectations and pose potential challenges to the Fed.

Chart 1. Dispersion of yr/yr price increases of components of CPI

Note: Histogram excludes price changes that exceed 15% yr/yr.

The Fed’s perspective on inflation may finally be changing. Up until recently, the Fed has argued strenuously that inflation is transitory and can be attributed to large price changes of select goods unusually affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, such as used vehicles, that have had an outsized impact on headline inflation. As recently as the Fed’s Jackson Hole Symposium on August 27, 2021, Fed Chair Jerome Powell stated, “the spike in inflation is so far largely the product of a relatively narrow group of goods and services that have been directly affected by the pandemic and the reopening of the economy … we would be concerned at signs that inflationary pressures were spreading more broadly through the economy.” Contrast his relatively sanguine tone two months ago to his statements on October 22, 2021, in which he asserted, “the risks are clearly now to longer and more persistent bottlenecks, and thus to higher inflation.”

As measures of headline inflation have risen, policymakers have frequently referred to the concept of ”broad-based price pressures” without providing numeric guidance on what ”broad-based” implies. The recent change in the Fed’s perception likely reflects increases in broad categories of the PCE price index and select measures of inflation like the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland’s Trimmed mean CPI and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s Underlying Inflation Gauge, both of which have tilted up.

This report presents detailed data on the distribution of price changes across over 200 expenditure categories in the CPI and PCE price index. They conclusively illustrate how prices are rising more broadly across the economy.

Consumer Price Index (CPI) distribution

Table 1 lists the proportion of expenditure categories in the CPI that rose more than 3%, 6%, and 10% yr/yr for two observations prior to the pandemic, in January 2021 when inflation began accelerating and in September 2021. The shift in the distribution of price increases is striking: in January 2020, one-fourth of expenditure categories rose by more than 3% yr/yr; in September 2021, that figure had risen to 57%. The distribution of prices has also become more “extreme” with prices rising and falling by greater magnitudes. In January 2020, only 5% of prices across all CPI expenditure categories rose by more than 6% yr/yr; that proportion increased to 27% in September 2021, while yr/yr price increases exceeding 10% have jumped from 2% of categories to 11%. There are substantially fewer expenditure categories that experienced price decreases yr/yr in September 2021 compared to January 2020.

Table 1. Portion of CPI components with price increases above 3%, 6% and 10%

| Sept 2018 | Jan 2020 | Jan 2021 | Sept 2021 |

Proportion > 3% yr/yr | 21% | 26% | 40% | 57% |

Proportion >6% yr/yr | 7% | 5% | 12% | 27% |

Proportion > 10% yr/yr | 3% | 2% | 0.5% | 11% |

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, author’s calculations | ||||

An important caveat is to note that the data and distributions are “unweighted” and do not account for each expenditure category’s contribution to headline CPI inflation, and that some expenditure categories are not seasonally adjusted. We consider that issue below when we discuss the PCE price index.

The pronounced rightward shift in the distribution of yr/yr price changes reflects a combination of supply shortages and strong demand. Supply shortages are accentuating the rise in production costs, and the strong demand is providing businesses the flexibility to raise product prices.

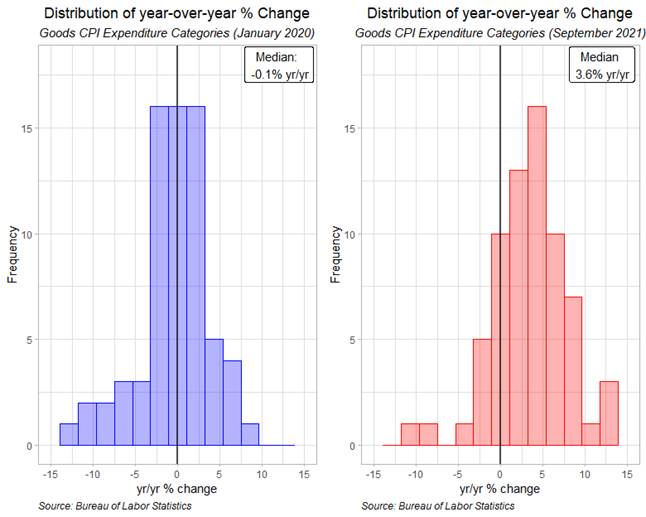

Restricting attention to inflation of goods excluding food, Chart 2 illustrates the clear shift up in the year-over-year price change distribution between January 2020 and September 2021. (The BLS data include a very large number of food categories and, similar to some BLS calculations, we exclude food prices from the goods prices analysis.) The yr/yr change in the median component of the CPI for goods excluding food was -0.1% in January 2020 compared to 3.6% in September 2021. Since the onset of the pandemic, a surge in consumption of goods and decline in consumption of services has shifted the composition of spending. Strong product demand in conjunction with a rolling wave of supply constraints (ongoing semiconductor shortages, port closures, trucking and freight bottlenecks, extreme weather events, etc.) has pushed goods inflation substantially higher than its recent historical trend. As we note in Inflation Watch, prices of durable goods have risen 7% yr/yr, their first material rise since 1995. Prices of services excluding energy services have accelerated by a more moderate 2.9% yr/yr.

Chart 2: Distribution of yr/yr % change in Goods excluding Food

PCE price index distribution

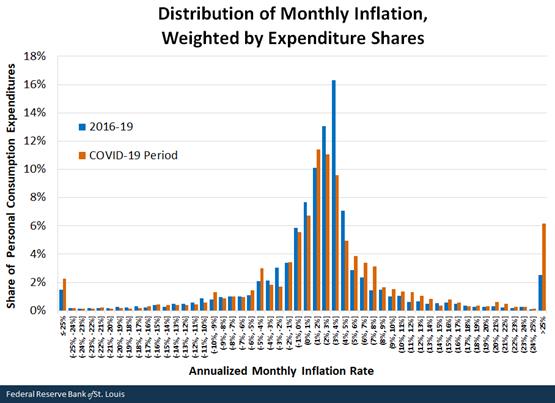

A research report published by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (Fernando M. Martin, “How Widespread are Price Increases in the U.S.?”) investigated how the distribution of price changes in the PCE weighted by expenditure shares evolved between 2016-19 and the COVID-19 period (Chart 3). The research highlights a similar rightward shift in the distribution of PCE price index, in which the PCE components are weighted by a product’s expenditure share, suggesting the price increases have widened, whether they are weighted by expenditure shares or not. The rightward shift in the price changes in the PCE price index highlights the increased contribution of the rapid price increases of goods and services with large yr/yr price increases to headline inflation and thus a broadening of inflation pressures. In particular, during the pandemic, approximately 6% of consumption was on goods and services that experienced price increases above 25% on an annualized monthly basis. In his study, Martin notes “their [durable goods] contribution is too small to be the only driver of higher inflation. That is, the shift in the distribution of inflation appears more generalized across categories.”

Chart 3.

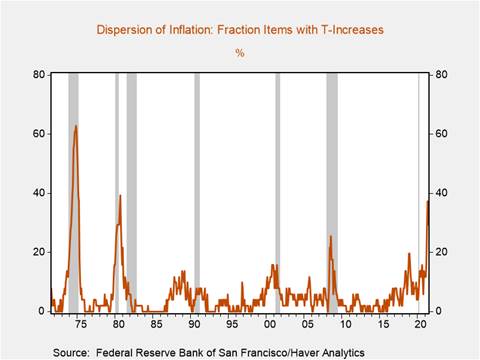

Measures of PCE inflation dispersion compiled by the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco provide further context on the degree to which price increases are distributed across expenditure categories. The three-month moving average of the percentage of items with price increases has risen sharply to 84%, above its historical average of 78%. However, this measure does not account for the magnitude of price changes relative to their recent trends. A measure of inflation dispersion that does account for this is the percentage of items of the PCE price index that have experienced yr/yr percentage price increases more than two standard deviations above their trailing five-year average. This measure surged to 37% in June, before edging down to 29% in July and remains at its highest level since 1980 (Chart 4).

Chart 4.

Another measure of consumer prices that indirectly captures the broadening of price acceleration is the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland 16% trimmed mean CPI. It excludes from its inflation measure the 8% of CPI components experiencing the largest monthly percentage price increases and the 8% with the largest declines. That measure has risen to 3.5% yr/yr from an average of 2% during 2012-19, and has risen at a 5.3% annualized pace in the last six months. This is consistent with our findings using the CPI expenditure category data.

Implications of the broadening of price increases

Price pressures have clearly broadened relative to their historical trend, putting the Fed in a difficult position. The Fed’s stance has recently shifted from asserting inflation has been driven by a select number of items to acknowledging at its November FOMC meeting the impact and persistence of supply bottlenecks and strong demand. One key takeaway is that broad-based price increases across expenditure categories and the shifting mix of consumption will heighten the difficulty in reducing core inflation, consistent with the Fed’s longer-run price stability mandate of 2% inflation.

As public health concerns surrounding the delta variant’s disruptive impact on activity wanes, allowing economic activity to return to normal, demand for services will only strengthen. This uptick in demand will occur when labor markets are historically tight, characterized by strong labor demand dramatically outstripping labor supply. Coupled with the anticipated hiring spree firms will need to meet staffing requirements for the upcoming holiday retail season, these pressures point toward continued acceleration in wages and operating costs. Labor supply will rise with the expiration of pandemic unemployment insurance, return to in-person schooling, the waning of pandemic health concerns constraints, and the rundown of household savings.

Yet we anticipate increases in labor supply will be overwhelmed by strong demand and the catch-up of wages to the unanticipated rise in inflation, so service sector wage and input pressures are decidedly skewed to the upside. The implications for broad-based inflation are that, while price increases of goods may moderate as supply constraints ease in Q2/Q3 2022, service sector inflation is likely to accelerate, driven by strong demand and rising healthcare and shelter prices. To date, the shelter component of the CPI—by far its largest—has risen only modestly to 3.15% and seems bound to accelerate significantly further, catching up to soaring home prices and observed rental costs.

Another implication of broad-based price increases is their impact on household inflationary expectations. Our hunch is that household inflationary expectations adjust more quickly and more elastically the more broad-based price increases are. To illustrate, imagine walking into a grocery store and noting that prices of all items have risen 5% on average. Presumably this would have a bigger impact on household inflation expectation formation than if the price of just a few items had increased 20% while prices of all other items had remained relatively unchanged. This may explain some of the marked rise in short-medium term measures of household inflationary expectations, and raises the risk that inflation begins to substantively impact wage and price setting behavior more persistently. Behavioral research is finding that the prices of frequently bought items are influencing household inflationary expectations (Francesco D’Acunto, et al, “Exposure to Grocery Prices and inflation Expectations, 2020).

Evidence based on manufacturing and service industry PMIs and surveys suggests that an overwhelming majority of businesses are experiencing rising input costs and are raising prices, consistent with the evidence that prices are increasing throughout the economy.

If supply disruptions and bottlenecks linger well into 2022, as the Fed now anticipates, and if aggregate demand in the economy continues to grow at a solid pace, as we forecast, then price increases are likely to remain broad based. In such a scenario, upward pressures on inflation would persist. As Powell emphasized in his press conference following the FOMC meeting, forecasting economic activity and inflation is always difficult, particularly as we emerge from the pandemic. This analysis of granular data of CPI price movements confirms our view that inflation risks are skewed to the upside.

Mickey Levy, mickey.levy@berenberg-us.com

Mahmoud Abu Ghzalah, mahmoud.abughzalah@berenberg-us.com

© 2021 Berenberg Capital Markets, LLC, Member FINRA and SPIC

Remarks regarding foreign investors. The preparation of this document is subject to regulation by US law. The distribution of this document in other jurisdictions may be restricted by law, and persons, into whose possession this document comes, should inform themselves about, and observe, any such restrictions. United Kingdom This document is meant exclusively for institutional investors and market professionals, but not for private customers. It is not for distribution to or the use of private investors or private customers. Copyright BCM is a wholly owned subsidiary of Joh. Berenberg, Gossler & Co. KG (“Berenberg Bank”). BCM reserves all the rights in this document. No part of the document or its content may be rewritten, copied, photocopied or duplicated in any form by any means or redistributed without the BCM’s prior written consent. Berenberg Bank may distribute this commentary on a third party basis to its customers.