Strong U.S. growth, inflation, and the Fedâs challenges

Key aspects of the current U.S. macro situation are seemingly inconsistent or unsustainable. The current thrust of monetary policy, highlighted by the Federal Reserveâs zero percent interest rate and massive purchases of Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities (MBS), is inconsistent with the Fedâs longer-run objectives and unsustainable. The 10-year Treasury bond yield has risen to 1.15% but remains below inflation and inflationary expectations, which seems inconsistent with an economy that will eventually recover back to normal. In the real economy, millions of unemployed persons remain sidelined by the pandemic, and the amount of âexcessâ personal savings is dramatically higher than at any time in history. Inflation remains fairly subdued. Now, full recovery from the pandemic is in sight. What adjustments can we expect?

In summary:

*The economy is projected to strengthen dramatically as vaccines are successfully widely administered and the negative impacts of the pandemic ebb. We expect the U.S. economy in 2021 to enjoy the strongest growth in decades, with momentum carrying through 2022 (Already strong U.S. economic growth outlook revised up further, January 29, 2021). Global economies should also recover (Global outlook 2021: strong rebound ahead, January 8, 2021).

*U.S. inflation will rise moderately through 2021 and upward price pressures will continue in 2022. The pipeline of monetary and fiscal stimulus is unprecedented, with huge deficit spending and a surge in broad monetary aggregates and excess personal savings. This will generate excess aggregate demand that will facilitate increases in prices and wages and higher expectations of inflation.

*Inflationary expectations are expected to rise in anticipation of mounting inflation pressures and add to price increases and pose a challenge for the Fed. This is most likely to unfold as the economy strengthens and high frequency data and anecdotal evidence of rising prices and wages enter the macro narrative.

*Bond yields are projected to rise, reflecting increases in real rates and inflationary expectations. By year-end 2021, 10-year Treasury bond yields are projected to rise to 2%, about where they were prior to the pandemic, and then rise modestly higher in 2022.

*The Fed is focusing nearly exclusively on pumping up the economy and jobs. In late summer or fall, against the backdrop of economic strength, it will announce a schedule to begin tapering its asset purchases in early 2022. Markets will take that as a signal that rate hikes will eventually follow. The Fedâs ability of managing bond yields is limited.

*The U.S. economy is expected to lead recoveries in Europe, the UK, Japan, and other advanced nations, and its higher inflation and bond yields will have spillover international effects.

Assessment of the economic recovery

To date, real GDP has recovered 76% of its sharp contraction in H1 2020, while employment has lagged and has recovered 56% of its decline (Charts 1 and 2). Goods consumption and production have fully rebounded, soaring above pre-pandemic levels. Recovery in the services sectors still lag. Employment mirrors that trendâthrough January, employment remains 9.9 million below its pre-pandemic level, primarily in the services sectors (Charts 1 and 2). The massive income support provided by the CARES Act boosted disposable incomes and contributed to the strong but partial recovery in output and jobs. As predicted earlier, the sharp contraction and insufficient demand generated temporary declines in the price indexes, and inflation has remained subdued as the economy recovers (Temporary moderate deflation despite aggressive monetary expansion, April 28, 2020). Bond yields plummeted to historic lows in Q1 2020 and have risen, but only modestly, and remain well below pre-pandemic levels (Chart 3).

Chart 3:

Following the early sharp but partial recovery, the pace has temporarily slowed, reflecting the negative impacts of the second wave of the pandemic, but is set to reaccelerate sharply. We forecast 6.5% real GDP growth in 2021 and continued momentum in 2022 with 4.5% growth. Real GDP is projected to regain its pre-pandemic level by Q2 2021 and be 7.6% above it by year-end 2022. Following its slow start, employment is estimated to rise 7 million in 2021, leaving it 3 million below its pre-pandemic peak by year-end.

Nominal GDP, the broadest measure of current dollar spending in the economy, after falling 1.2% in 2020 (Q4/Q4), is projected to increase by 15% cumulatively in 2021-2022. As the economy returns to normal beginning in Spring 2021, activity and jobs in the services sector will lead, while the goods sectors, including consumption, housing, and exports, are expected to register further strong gains.

Fiscal and monetary stimulus. This forecast is based on the unprecedented pipeline of monetary and fiscal stimulus, and our expectation that approximately 60% of the Biden Administrationâs proposed $1.9 trillion in additional deficit spending will be enacted. Even before the recent round of $600 checks were distributed under the âConsolidated Appropriations Act, 2021â passed in late December and Bidenâs proposals, the governmentâs unprecedented legislated transfer payments had resulted in sizable increases in personal disposable income. The governmentâs generous fiscal policies supported disposable income and consumption amid massive unemployment. But, combined with constraints on spending and cautionary behavior, the transfer payments also contributed to a surge in personal savings of approximately $1.5 trillion above pre-pandemic levels. Some of that saving was put in the stock market, but a sizable portion is sitting in bank deposits, earning virtually zero interest.

Monetary policy was equally aggressive. The Fedâs asset purchases have driven up the supply of bank reserves (the monetary base has risen 54% year over year). Also, M2 has also surged 26% year over year, in sharp contrast to the period following the financial crisis, when the Fedâs QEs did not generate any sustained pick up in M2 or any acceleration in economic activity (Money supply spike: sources and implications, July 1, 2020).

Labor markets. Labor markets, the top priority of the Biden Administration and the Fed, have been slower to recover and will likely lag the improvement in GDP. Although the unemployment rate has declined sharply to 6.3% in January, this reflects a decline in the labor force participation rate (LFPR) as well as a rebound in jobs. The employment-to-population ratio has recovered significantly to 57.5% from its trough of 51.3% in April 2020, but it remains well below its pre-pandemic level of 61.1%, suggesting the dramatic decline in the unemployment rate overstates the degree of labor market improvement (U.S. labor market: big gains, big shortfalls, December 9, 2020).

We project the unemployment rate will fall to 4.8% by year-end 2021 and 4.2% by year-end 2022, still above its 50-year low of 3.5% before the pandemic. As the economy gets back to normal, people will re-enter the workforce, but it will take a while for the LFPR to rise back to its prior level. Moreover, the unemployment rates and employment of different groups, including Black and Hispanic persons, were harmed more than average in H1 2020 and have been slower to improve. If the Biden proposal to increase the minimum wage to $15/hour is enacted, the recovery in employment of younger people and lower income people will be slower (Congressional Budget Office, The Budgetary Effects of the Raise the Wage Act of 2021, February 8, 2021). These issues are important to the Fed, which has raised the priority of inclusive employment.

Inflation and inflationary expectations

Inflation is projected to increase and we expect inflationary expectations to rise in anticipation of mounting inflation pressures. Whether inflation rises moderately above 2% or by more depends critically on the sustainability of the acceleration of aggregate demand. Following temporary declines in price indexes in March-April 2020 that significantly reduced year-over-year measures of inflation, price increases have picked up, but year-over-year inflation remains well below pre-pandemic levels. In the last six months, the PCE price index has risen at a 2.4% annualized pace and 2.2% on its core, lifting its year-over-year rise to 1.3% and 1.5% on the core. The six-month annualized rise in the PCE price index for core goods presumably reflects the strong demand for consumer goods amid supply bottlenecks (Chart 4). The PCE price index for core services, which comprise 65% of consumer prices, has followed a similar pattern, accelerating to an annualized pace of 2.5% over the last six months, despite many services sectors, including leisure and hospitality, largely crippled (Chart 5).

Rising inflation in the U.S. would lead a new trend of higher inflation in advanced nations (Berenberg, Inflation: lower for longer is not forever, Sept 10, 2020).

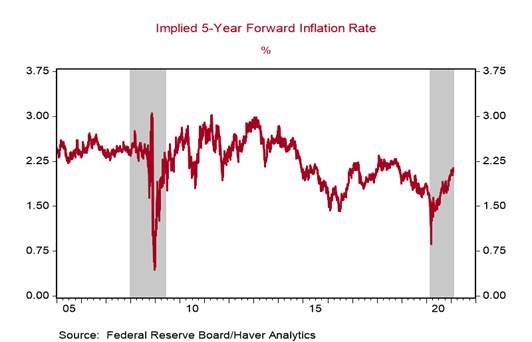

Inflationary expectations also dipped at the onset of the pandemic but have since recovered. Currently, inflationary expectations implied by breakevens on TIPS have risen slightly above 2% (Chart 6). Survey-based measures of consumer inflation expectations have increased to levels last seen in 2015, but remain modest.

Chart 6:

In the coming months, CPI inflation will temporarily exceed 3% year over year as a consequence of a combination of higher oil prices that will boost retail energy prices and the base effect in which the declines in the price indexes in March-April 2020 will be replaced with increases in those months this year. Inflation will then settle down a bit, but only temporarily.

Sustained upward pressures on inflation will begin to mount in the second half of 2021 and carry into 2022, as the stimulus-fueled economic recovery will involve excess aggregate demand relative to productive capacity. Strong product demand will provide businesses flexibility to raise product prices. This trend is already apparent for consumer goods (U.S. inventories low, contributing to higher goods prices, February 11, 2021). The same pattern will unfold in prices of services, but this is most likely with a lag following the reopening of services sectors and a return to normalcy.

Commodities and materials prices. Some indicators of price increases and inflation risks have already been rising significantly. The U.S. dollar has weakened, partly in response to the Fedâs aggressive quantitative easing and its new strategic framework that favors higher inflation. In response, price of non-petroleum imports has risen 3.8% annualized in the last six months, lifting the year-over-year rise to 1.8%. Prices of industrial commodities and materials have soared. The S&P GSCI industrial metals price index plummeted in Q1 2020 but is now rising 32% year over year (Real-time insights, economic and financial pulse, February 8, 2021). Agricultural and livestock prices have increased nearly as much. Oil prices have risen dramatically from pandemic lows, with the WTI crude oil price now above $57 per barrel. An energy price index composite that includes oil, gas, and home heating oil has rebounded sharply and is back to its pre-pandemic level.

Wages and other operating costs are expected to rise as well. High demand for workers in some manufacturing sectors and construction has already begun to push up wages. So far, in the service-producing industries, average wages have jumped in retail trade and transportation and warehousing, while wages in the large leisure and hospitality sector have decelerated, reflecting the sharp curtailment of activities. As the economy reopens, the service sectors will get the biggest boost, and the demand for labor will rise. Labor supply is relatively elastic, as highlighted by the continuous rise in the prime working-age labor force participation rate in the second half of the 2009-2019 expansion, tempering wage increases, but sustained strong product demand will affect both wage and price setting behavior.

Economic policies such as the initiative to raise minimum wages and regulations may add to wage pressures and operating costs, at least on the margin. Big increases in legislated minimum wages will have their largest direct impact on low wage/low productivity sectors, particularly leisure and hospitality and retail trade, which have been among the most harmed by the pandemic. In addition, renewed regulations on industries and labor markets may add to operating costs while reducing productivity. From a macroeconomic growth perspective, these impacts will be overwhelmed in the near term by the stronger aggregate demand generated by the monetary and fiscal stimulus, but some of the increases in operating costs will result in higher product prices.

The critical issue for sustained inflation is the extent to which these higher operating costs are passed onto consumers at the retail, wholesale, and manufacturing levels. This depends on aggregate demand. If economic activity accelerates as we forecast, with 15% cumulative growth in nominal GDP in 2021-2012, businesses will have flexibility to raise product prices. This will allow businesses to generally maintain their profit margins, but it will be reflected in higher inflation.

Critically important, the rise in inflationary expectations in anticipation of actual inflation pressures will contribute to higher bond yields and will also influence the Fedâs perception about inflation. As actual inflation drifted lower the last decade despite persistent declines in the unemployment rate, the Fed acknowledged that the Phillips Curve was flatter than it had previously thought, and placed more emphasis on the role of inflationary expectations in the inflation process.

The Fedâs sanguine outlook on inflation relies heavily on the low inflation experience of the last decade. However, the history of inflation during periods of high deficits and easy monetary policy tells a different story (Do enlarged fiscal deficits cause inflation: the historical record, Bordo and Levy, January 19, 2021). Moreover, the primary reason why inflation remained low during the last expansion is the Fedâs monetary stimulus failed to stimulate any sustained acceleration in aggregate demand. Nominal GDP growth averaged slightly above 4%, so real growth averaged 2.25% and inflation 1.75%. In the current episode, if the monetary and fiscal policies actually stimulate sustained strength in aggregate demand, the inflation story will be different.

The recent rise in inflationary expectations is consistent with the increases in commodity and materials prices, the weaker U.S. dollar, and expansive fiscal and monetary policies (Chart 7). Whether inflationary expectations rise further and support inflation pressures remains a critical issue.

Chart 7:

As the economy reopens and strengthens, we expect a rise in confidence and a positive narrative on economic performance will lift inflationary expectations on Main Street as well as in financial markets. Indicators of stronger product demand are likely to be associated with reports of insufficient inventories and supply constraints, and anecdotal evidence of businesses raising prices.

Technological innovations and quality adjusted inflation. One mitigating factor that has constrained higher inflation has been technological innovations and productivity gains, and these will continue to keep a lid on inflation. In addition to new products, advancements in the distribution of goods has reduced prices of goods and services. The Bureau of Economic Analysisâ (BEAâs) official inflation indexes are based on surveys of product prices that are adjusted for estimates of quality improvements in new products and services.

Quality adjustments have had a pronounced impact on the PCE price index of durable goods, which has declined 38% over the last 26 years, despite sizable increases in many product prices (Chart 8). (For example, the average sticker price of an automobile has roughly tripled since the mid-1990s, but, because of estimated quality adjustments, the BEAâs PCE price index for automobiles and parts has risen only 9% since January 1995.) The PCE price index of nondurable goods has increased 1.5% annualized, with wide fluctuations driven by swings in energy prices. Quality adjustment in services is much more difficult to measure (i.e., medical services), and in many services, quality has not improved much over time. Reflecting this, the PCE price index for services has risen at an average annualized pace of 2.6% since the mid-1990s, and 2.1% during the 2009-2019 economic expansion.

Chart 8:

While technological innovations and quality will continue to advance, they will constrain inflation but not prevent it from rising.

Bond yields

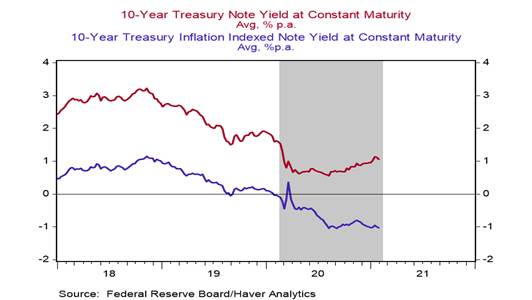

The current 1.15% yield on 10-year Treasury bonds is seemingly inconsistent with the drift up in inflationary expectations and prospects of full economic recovery, even with the Fedâs aggressive purchases of Treasury debt securities. Inflation-adjusted yields hover near an all-time low (Chart 9). Several months prior to the onset of the pandemic, in December 2019, nominal yields were 1.9%. They are expected to recover beyond that level.

Chart 9:

Certainly, the Fedâs large asset purchases and its forward guidance that it will continue its QE and zero interest rate policy has been a major factor keeping bond yields low. In 2020, the Fed purchased $2.4 trillion of Treasuries, 70% of the deficit spending. It also purchased $0.6 trillion of MBS. With the government-sponsored agencies Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac still under conservatorship of the Treasury, their debt effectively has the full faith and credit of the U.S. government. The share of new deficits purchased by the Fed will be constrained by further legislated increases in deficit spending, and the residual must be absorbed in the markets.

The higher yields of U.S. Treasuries relative to yields on leading global government debt (Japan, Germany, Switzerland, UK) will support foreign demand and constrain the rise in U.S. yields. However, ex ante real yields on U.S. Treasuries are below some overseas yields such as Japanese JGBs. Moreover, foreign demand for U.S. Treasuries may also be tempered by expectations that the U.S. dollar may fall further.

As the economy reopens and growth strengthens, real rates and inflationary expectations are both expected to rise. The timing and magnitude of the rise in bond yields is uncertain, and history suggests that any rise is unlikely to be smooth and gradual. Moreover, contrary to the perception of many market participants, the Fed is limited in its ability to control bond yields for more than a short period.

The Federal Reserve

Currently, the Fedâs objectives of pumping up the economy and generating a rapid recovery in employment are closely aligned with the Biden Administrationâs objectives, and the Fed continues to signal that it is comfortable with extending its current 0% interest rate and QE policies. In its new strategic plan, the Fed favors inflation above 2% to make up for recent years of sub-2% inflation (The murky future of monetary policy, Levy and Plosser, October 5, 2020). Although it has not provided a range of inflation that it is comfortable with, the Fed has clearly raised the bar for pre-emptive monetary tightening (Fed Shifts to âFlexible Form of Average Inflation Targetingâ , August 27, 2020). The Fedâs new strategy establishes maximum inclusive employment as its mandate, and Chair Powell and other Fed members have indicated that it places a higher priority on its employment mandate than inflation, as long as inflationary expectations remain anchored to 2%.

All of this suggests that, as long as inflation and inflationary expectations remain anywhere close to 2%, the Fed will sustain its current policies. Ultimately, the Fedâs policies will be driven by the economy, employment, and inflation. But it is important to emphasize that the Fedâs policies may be constrained by its desire to keep inflationary expectations anchored to 2%.

The Fedâs economic projections. The Fedâs quarterly Summary of Economic Projections (SEPs) provide important insights. In its most recent December 2020 SEPs, the median Fed member projected real GDP would grow 4.2% in 2021 and 3.2% in 2022, the unemployment rate would fall to 5% at year-end 2021 and 4.2% at year-end 2022, and that core PCE inflation would be 1.8% in Q4 2021, 1.9% in Q4 2022 and 2.0% in Q4 2023. It is ironic that the Fedâs inflation forecast is inconsistent with its stated objective of raising inflation above 2%. The median Fed member forecast that the Fed funds rate would remain at zero through the 2023 projection period, but five Fed members projected that it would be appropriate to rate the funds rate by the end of 2023.

We anticipate that the Fed will revise up its forecasts of real GDP and inflation, and a larger number of FOMC membersâclose to a majorityâare expected to forecast that it will be appropriate to raise the Fed funds rate in 2023. Actual growth has persistently exceeded the Fedâs recent SEPs, while the unemployment rate has fallen by much more, and the Fedâs new forecast will reflect the additional fiscal stimulus enacted in December, and the likely possibility of more under the Biden Administration. We note that our forecast of real GDP is far above the most optimistic forecast in the full range of FOMC members.

The central tendency forecasts of inflation are most likely to rise for 2021 and 2022, and the upper bound of the range of FOMC member forecasts will rise. The anticipated upward revision of inflation forecasts will better align the projections with the Fedâs objectives.The anticipated upward tilt in the Fedâs dot-plot in 2023 will convey important insight.

The Fed understands that its current monetary policies are unsustainable, but it would like to avoid jarring financial markets. Although this poses a potentially tricky challenge for the Fed and its communications, the Fed will abide by its new strategic framework for achieving its dual mandate. Moreover, strong economic growth and the jobs recovery will provide support for its decision to begin unwinding. Of note, even the taper tantrum did not harm economic performance, and once the Fed actually began reducing its asset purchases in 2014, things went smoothly. Similar to the 2013-1014 episode, financial markets will likely link any Fed announcement of a taper to an eventual rise in interest rates, but that should be viewed as a positive.

We expect the Fed to announce in early Fall that it will begin tapering its asset purchases in early 2022, but even before then, certain signals will suggest that the Fed is moving in that direction. Currently, statements by Powell and other Fed members emphasize that the economy is digging out of a big hole and remains vulnerable, and that it is poised to expand monetary policy even further if necessary. That tone will change as the economy strengthens, employment increases resume, and real GDP expands well beyond its pre-pandemic level.

Against the backdrop of stronger growth and lower unemployment, the eventual winding down of the Fedâs massive QE followed by a liftoff from zero interest rates will be natural policy adjustments to economic normalization. Current policies were implemented as emergency responses to the pandemic and government shutdowns. Fed Vice Chair Richard Clarida recently stated the Fed estimates the natural real rate of interestâso-called r*âis 0.5%, which with 2% inflation implies a neutral Fed funds rate of 2.5%. The problem is financial markets crave monetary easing, and buoyed by the recent experience of subdued inflation over the last decade, market adjustments are possible.

The timing of the Fedâs unwinding its emergency policies may also be influenced by any material rise in inflationary expectations. Over the last decade, as inflation remained subdued despite the lower unemployment rate, the Fed acknowledged the Phillip Curve was flatter than it had earlier believed, and it placed a larger emphasis on the role of inflationary expectations in the inflation process. If inflationary expectations were to rise sufficiently above 2% to become âunanchored,â the Fed may be forced to respond quicker.

Mickey Levy, mickey.levy@berenberg-us.com