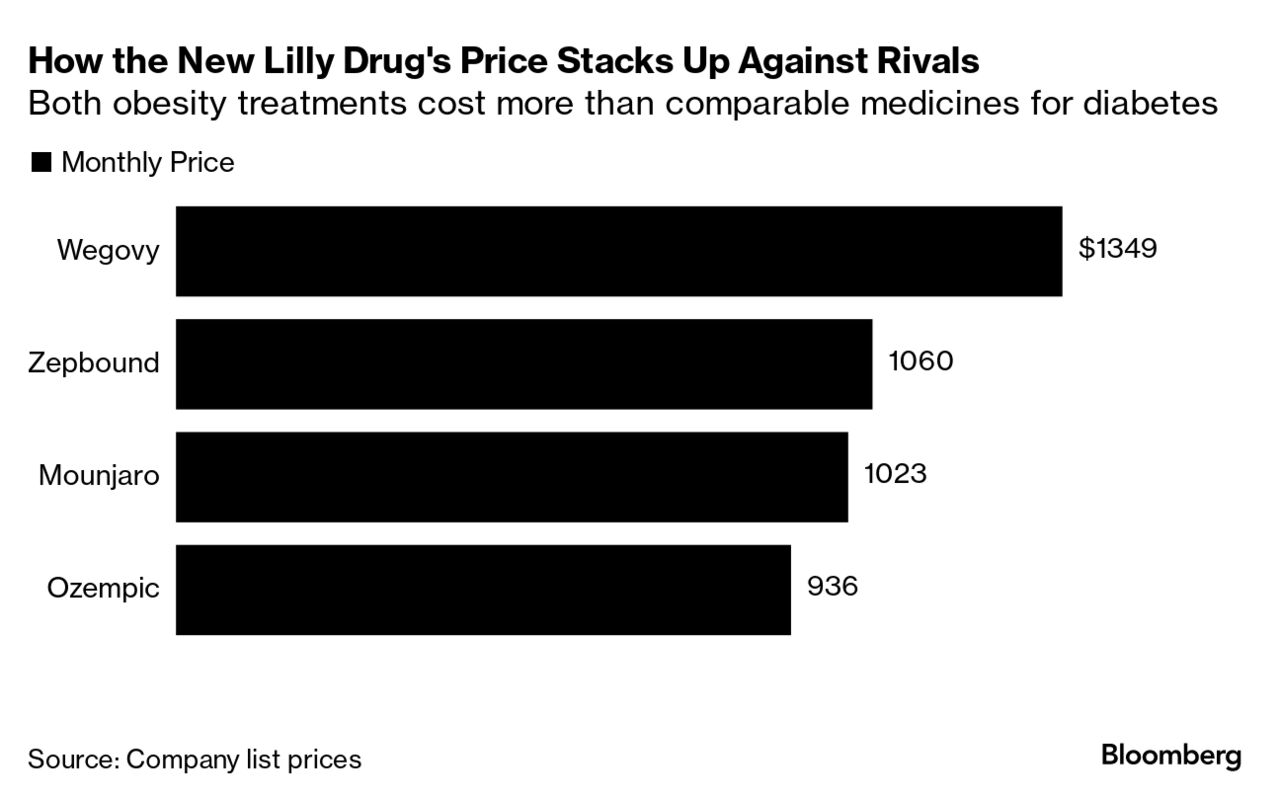

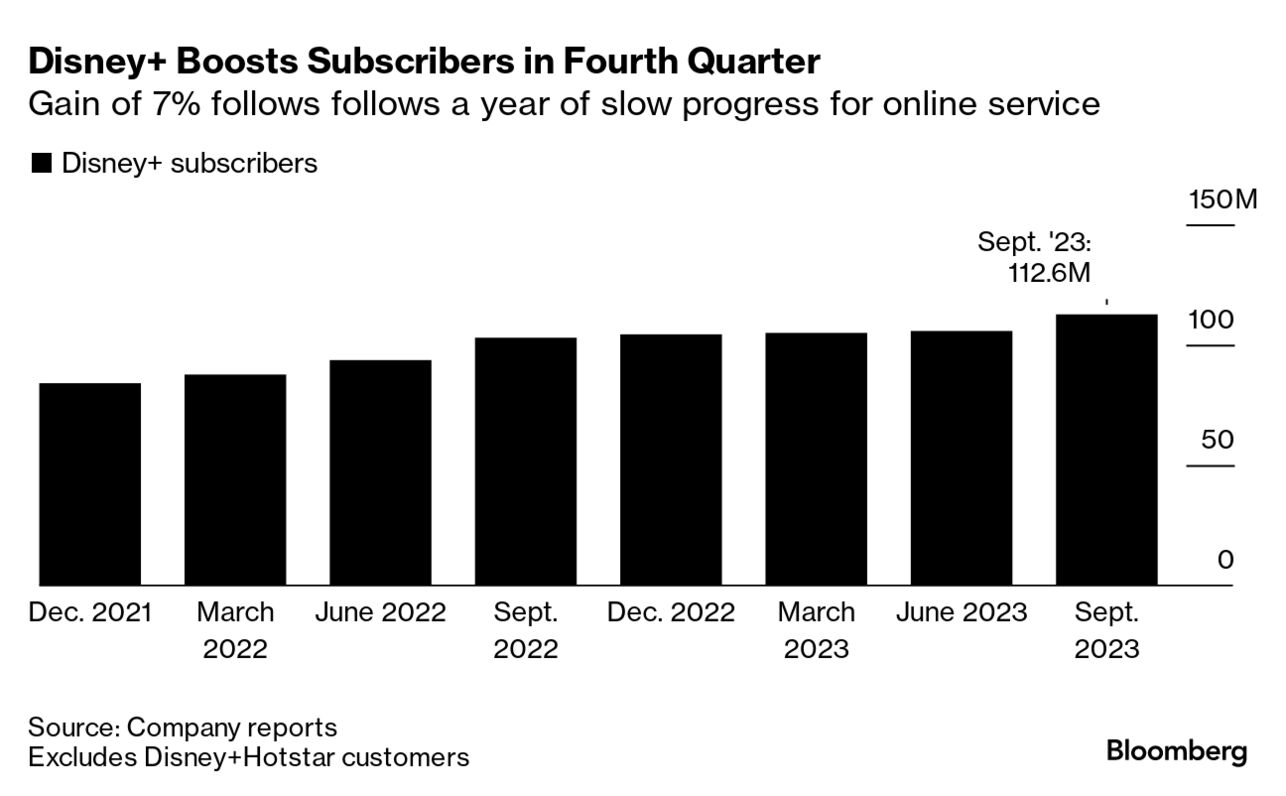

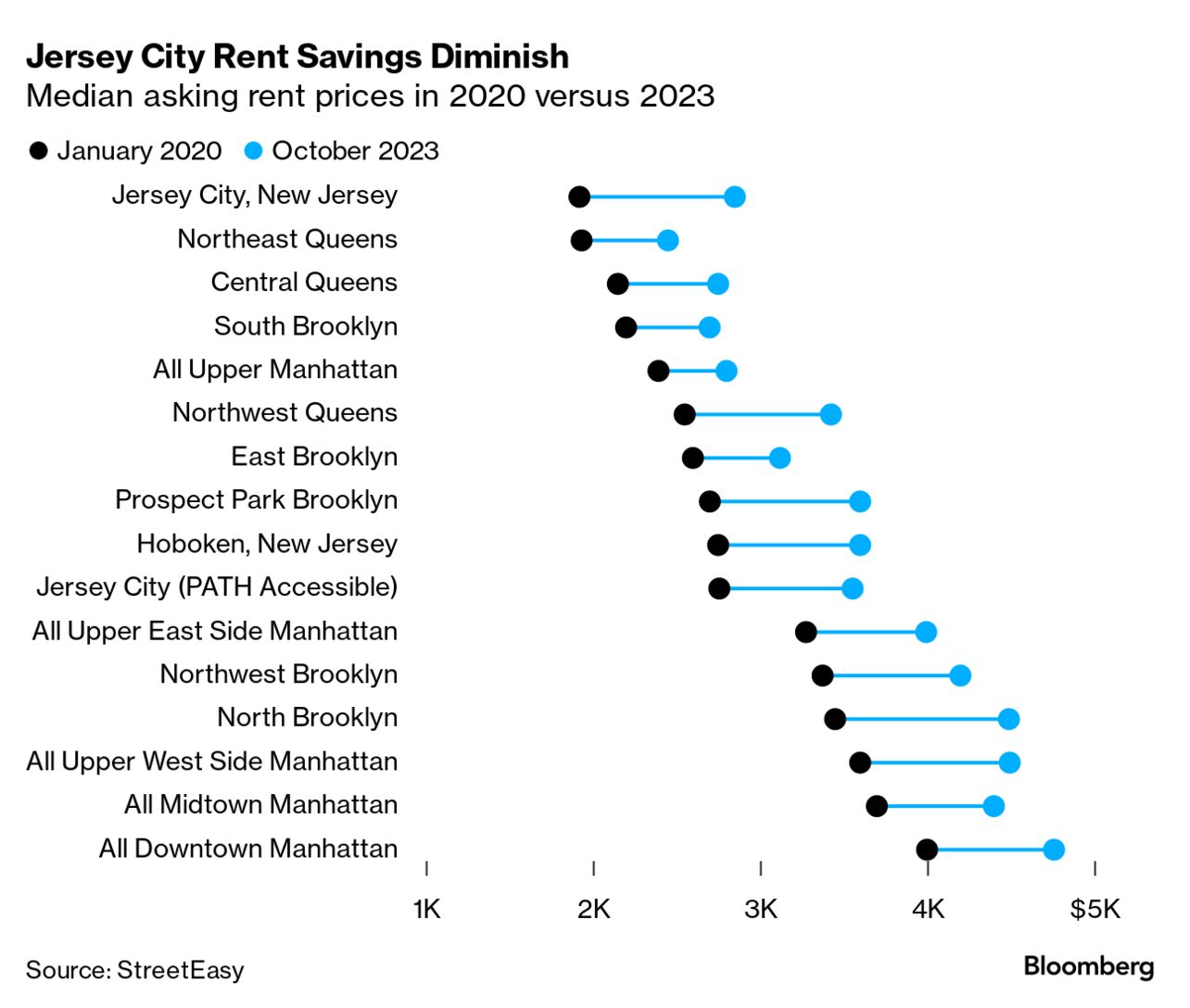

| The $100 billion market to make everyone thinner just got more crowded. Eli Lilly won US approval to use the active ingredient in its diabetes drug as a treatment for obesity. Zepbound, as the new weight-loss treatment is called, will cost $1,059.87 for a month’s supply. That’s cheaper than Wegovy, a similar drug made by Novo Nordisk, which is $1,349 for a month’s supply. The mania over weight-loss drugs is drawing responses from all kinds of industries, including airlines, dialysis centers and big box chains like Walmart. Lilly wasn’t allowed to market its diabetes drug, Mounjaro, for obesity prior to Wednesday’s approval. The promise of these drugs has boosted Lilly and Novo to record heights—Lilly is now the most valuable health-care company in the world. But with the frenzy comes the still-open question about any possible long-term health risks that may be associated with weight-loss drugs. Eli Lilly says Zepbound will be available soon after Thanksgiving. —David E. Rovella War, geopolitical tension and inflation were among the litany of risks identified by political and business leaders speaking at the Bloomberg New Economy Forum in Singapore on Wednesday. The world is facing a “moment of danger” with wars in Ukraine and Gaza and “tripwires” that could trigger conflict in Taiwan and the South China Sea, Singapore Foreign Minister Vivian Balakrishnan said as the three-day event got underway. “I’m very uncomfortable.”  Vivian Balakrishnan, Singapore’s foreign affairs minister, during the Bloomberg New Economy Forum in Singapore on Wednesday. Photographer: Lionel Ng/Bloomberg China disagrees with the increasingly popular comparison to Japan and its era of economic stagnation. “China’s current situation is vastly different from what Japan used to be in,” argued Liu Shijin, a member of the People’s Bank of China’s monetary policy committee, during a speech at the Financial Street Forum in Beijing. He pushed back on claims the country is falling into a “balance-sheet recession” like Japan did in the 1990s—where households and companies focused on paying down debt instead of spending or investing. Underwriters are pushing such a cautious approach to initial public offerings that it may be backfiring, contributing to the disappointing performance of recent listings. Banks have increasingly taken the conservative route of having a smaller float and allocating most of the book to long-term investors like mutual funds. That approach, said Kristen Grippi, Evercore’s head of equity capital markets, may deter portfolio managers from buying the shares in the aftermarket. Walt Disney posted better-than-expected fourth-quarter earnings and said it will seek an additional $2 billion in cost savings after terminating thousands of employees. The profit increase and expanded cost cutting will help Chief Executive Officer Bob Iger counter activist investor Nelson Peltz, whose Trian Fund Management controls a roughly $2.5 billion stake in Disney and plans to seek several board seats. Private equity is having a rough time of it lately, and that seems to be putting talented Wall Streeters in the drivers seat. Higher base salaries, more paid vacation, gym discounts, travel insurance—PE bosses are doing all they can to retain talent. With rising borrowing costs making fundraising and stake exits more challenging, buyout firms have become more selective in their hiring, and are focusing more on keeping existing staff happy. On the surface, Deutsche Bank, Citigroup and Mizuho Financial Group appear to be delivering on their promises to cut carbon emissions. The three banks (along with most of their peers) have committed to eliminating so-called financed emissions—the greenhouse gas-pollution enabled by their lending and investing. In their sustainability reports, all three banks have said their numbers have come down, in some cases significantly. But alas, a look at the fine print shows all is not as it seems. In New York City mythology, young strivers decamped from Manhattan for New Jersey because they couldn’t make it there (with anywhere yet to be determined). The westward migration typically meant lower rent, utilities, taxes and health costs. But the old calculus is changing as savings on rent across the Hudson evaporate. From the Ford Trimotor to today’s Airbus jetliners, there’s been one constant: Airplanes are almost always long tubes sporting wings with engines bolted on underneath. Now startup JetZero is taking aim at that design with a radical proposition: a triangle-shaped aircraft resembling a giant manta ray, boasting a shorter fuselage wide enough to contribute to the lift needed to stay airborne. It also claims the design is exceptionally green in an otherwise dirty industry: The startup says its so-called blended-wing aircraft could haul as many as 250 people—the capacity of a Boeing 767—on half the fuel.  JetZero’s blended-wing jet Illustration: JetZero Get the Bloomberg Evening Briefing: If you were forwarded this newsletter, sign up here to receive Bloomberg’s flagship briefing in your mailbox daily—along with our Weekend Reading edition on Saturdays. Bloomberg Green at COP28: World leaders will gather in Dubai on Dec. 4-5 in an effort to accelerate global climate action. Against the backdrop of the United Nations Climate Change Conference, Bloomberg will convene corporate leaders, government officials and industry specialists from NGOs, IGOs, business and academia for events and conversations focused on creating solutions to support the goals set forth at COP28. Register here. |