| Fund independent journalism with £5 per month |

|

|

|  | | | | Was rugby better in the old days? Try watching it and you will soon find out | | The game is infinitely more skilful and entertaining than in the past and nostalgists should be careful what they wish for | |  |  The quality of the 2023 Rugby World Cup quarter-final between France and South Africa was ‘as good as any in the history of the event’. Photograph: Paquot Baptiste/Abaca/Shutterstock

| |  | Michael Aylwin |

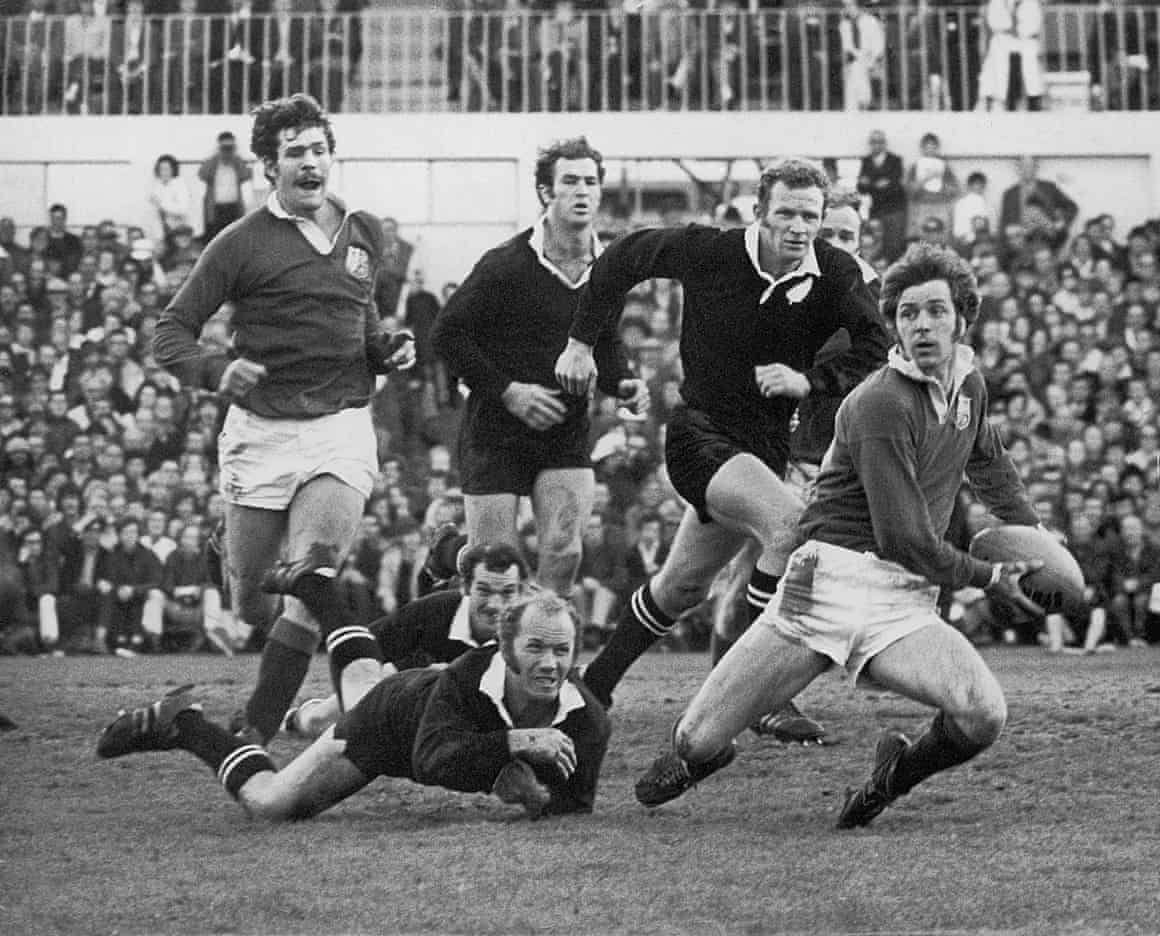

| | | Another week, another set of ideas for how rugby union can be improved. Another year, another panoply of breathtaking matches, any one of which, if they had taken place in the distant amateur era, would be hailed by those “who were there” as legendary. Last week Warren Gatland became the latest to offer his thoughts on how the game might move on. But in this age of social media incontinence we are never far from a thoughtless rant about how awful the game has become. Last year, meanwhile, a casual glance through just the match reports this correspondent has written reveals yet more extraordinary displays of skill and drama. From Newcastle’s 40-point victory over the champions Leicester on the first weekend, through France v Scotland in the Six Nations, Leinster’s win over Toulouse, Wales v Fiji at the World Cup and one weekend in Paris that has already passed into legend – and it happened less than three months ago. | | | | | | | | The quarter-finals of this year’s World Cup between New Zealand and Ireland on the Saturday and France v South Africa the next day were as good as any in the history of the event. The rugby was hailed by some, particularly the first half of the Sunday game, as the greatest ever played. A personal view is that, yes, they were astonishing, but also no more than the latest examples of a sport that seems to deliver weekend after weekend (viz the last couple of rounds of European rugby). So why do we keep bemoaning the quality of the modern game? And, worse still, holding up the 20th‑century version as some sort of golden age when players were skilful and looked for space instead of contact? It is difficult to evoke through words alone sufficient levels of contempt for the latter idea. Be in no doubt, all you nostalgists, rugby union was woeful in the amateur era. If you don’t believe that go back and watch it. All of it. From first whistle to last. And not that 101 Best Tries video your grandpa bought you for Christmas in 1987. Admittedly, to watch an entire 80 minutes from the amateur era is not easy, but videos of them do exist on the internet. While researching Unholy Union, the book I wrote with Mark Evans a few years ago on where rugby has come from and where it is going, I sat through the entirety of the second and fourth Tests of the Lions tour to New Zealand in 1971, counting the key metrics such as scrums, lineouts and tackles. | | |  |  Barry John (right) of the British & Irish Lions bursts away from New Zealand’s Sid Going during the 1971 Lions tour. Photograph: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

| | | | And I did it twice. So no one else would have to. There were slightly more set pieces (50-plus scrums, 50-plus lineouts) than there were tackles in both matches. It is worth pausing to consider that. The fourth Test in particular, a draw played out in blustery Auckland, was an incoherent mess of amateurs scrummaging, flapping, kicking, punching, elbowing, trampling and generally slip-sliding around. Sometimes with a ball somewhere near them. And we grew up being told what a legendary Test series that was. Undoubtedly the biggest disadvantage the modern game has against the old days is levels of scrutiny. No one is trying to pretend every match nowadays is a thrill-fest. No sport anywhere has ever managed to magic away its dross. The big problem now is that a person can watch six live matches a weekend on telly. A sport like rugby is laid bare, the brilliant never quite shaking off the stultifyingly bad. But just imagine if we were able to watch six live matches a weekend from the 1970s. That would be an experience to shake us from our nostalgia. That would do more for the popularity of the modern game than any tweak to the kicking laws. The other problem is, perversely, how good everything is. Including and especially defences. Players in the modern game are immeasurably more skilful than their predecessors – of course they are, they’re full-time professionals – and they look for space all the time. It is just that there is so much less of it now. There was footage of a try from some Welsh club match in the 1980s that did the rounds on social media a year or two ago. Nice simple handling down the line for a try in the corner, straight from a scrum. Beautiful skills executed simply. And barely a defender in sight. The play may have started from a scrum, but those defenders arrived on screen one by one, as if each had been released sequentially from a cage on the touchline. | | |  |  The France fly-half Matthieu Jalibert looks for space in the Rugby World Cup quarter-final against South Africa at Stade de France. Photograph: Xavier Laine/Getty Images

| | | | It is the modern game’s very excellence that would make such a try impossible today. Defences would never allow it. All the more extraordinary, then, that we see more spectacular tries in a season these days than any compiler could muster from the amateur era to fill a VHS for Christmas. There is far less space in the modern game than there used to be last century, when you could throw a picnic rug over a pack of forwards as they marauded from set piece to set piece, from punch-up to punch-up. And so there are far more collisions, which throws up genuinely serious issues for the modern game to ponder. But do not confuse that with players looking for contact over space. Or with a sport that has become boring and cynical. The opposite applies in both cases. Modern players are far nobler and more disciplined in the face of a more aggravating experience than their amateur predecessors, and they find far more space against more brutally constricting defences. In short, they and their sport are far, far better than they ever were. Let us be careful what we wish for. Rugby has always been a collision sport Only slightly less risible than this idea rugby was better in the old days is the lament that it is now a collision sport where once it was a contact one. Rugby has always been a collision sport. It is just that for most of its existence players were barely scratching the surface of what was possible. That is mainly a function of its status as an amateur sport for so long, but it is also because of science and nutrition and the 21st century’s lust for self-improvement. If a player wants to improve at rugby, they must consider (as well as the skill element) improving their pace, power and fitness. That process in itself must accentuate the collisions. We would have to go back to the 19th century for the key development that sealed rugby’s fate – and that, incidentally, of those other sports that evolved from it in the decades that followed. When the Football Association formed in 1863, it mandated a rule that forbade any player from running with the ball in their hands. Nowadays, only the goalkeeper can handle the ball in what was to become association football; in those days, everyone could. But the folk who favoured the football of Rugby School insisted that running with the ball was integral to their game, so they broke away. This established the key difference between the two. When players in football run with the ball, it is loose and at their feet. To win the ball back is possible without even touching them. In rugby, players run with the ball attached to them. There is no way of stopping them, still less of winning the ball back, other than physical assault. The assault need not be particularly violent, but it must be a collision. From that, all else follows. Rugby has always been a collision sport. That those collisions should become so intense is the main reason for the grumbling. But to demand they become less so is to demand the players become slower, weaker and less fit. To become worse at rugby, in other words. It is never going to happen. Three of rugby’s greatest hits From this era of magnificent rugby, three personal favourites: the 1999 World Cup semi-final between France and New Zealand (although I haven’t watched it since, so maybe it is not as great as I remember); the 2004 Heineken Cup semi-final between Munster and Wasps (likewise); and the 2021 Premiership semi-final between Bristol and Harlequins, when the latter recovered from a 28-0 deficit after half an hour to win in extra time (pretty sure this would still work its magic). | | |  |  The legendary All Blacks wing Jonah Lomu (right) playing his part in the memorable World Cup semi-final against France in 1999. Photograph: Jean-Loup Gautreau/AFP/Getty Images

| | | Memory lane Rob Howley touches down to score the winning try in the final moments, taking advantage of a dawdling Clément Poitrenaud’s mistake as Wasps beat Toulouse 27-20 in that 2004 Heineken Cup final. “Kings of Europe after the ultimate sting of stings,” is how Robert Kitson described it in these pages. | | |  | | | Still want more? Robert Kitson looks back at the 2023 Rugby World Cup and assesses how South Africa won the battle of fine margins. Mike Brown did his chances of a new Leicester deal no harm with his try-scoring display in the Premiership win against Bath. Adam Hathaway reports. Gerard Meagher was at Twickenham along with more than 75,000 supporters to see Harlequins defeat Gloucester. Title rivals Northampton and Sale went into battle at Franklin’s Gardens. Saints prevailed and Daniel Gallan was there to witness it. To subscribe to the Breakdown, just visit this page and follow the instructions. And sign up for The Recap, the best of our sports writing from the past seven days. | |

| | | … there is a good reason why people choose not to support the Guardian. | | Not everyone can afford to pay for the news right now. That's why we choose to keep our coverage of Westminster and beyond, open for everyone to read. If this is you, please continue to read for free.

Over the past 13 years, our investigative journalism exposing the shortcomings of Tory rule – austerity, Brexit, partygate - has resulted in resignations, apologies and policy corrections. And with an election just round the corner, we won’t stop now. It’s crucial that we can all make informed decisions about who is best to lead the UK.

Here are three good reasons to choose to support us today. | | 1 | Our quality, investigative journalism is a scrutinising force at a time when the rich and powerful are getting away with more and more. |

| | 2 | We are independent and have no billionaire owner controlling what we do, so your money directly powers our reporting. |

| | 3 | It doesn’t cost much, and takes less time than it took to read this message. |

| | Choose to power the Guardian’s journalism for years to come, whether with a small sum or a larger one. If you can, make the choice to support us on a monthly basis from just £2. It takes less than a minute to set up, and you can rest assured that you’re making a big impact every single month in support of open, independent journalism. Thank you. | | |

|

|

| | |

|

| Manage your emails | Unsubscribe | Trouble viewing? | | You are receiving this email because you are a subscriber to The Breakdown. Guardian News & Media Limited - a member of Guardian Media Group PLC. Registered Office: Kings Place, 90 York Way, London, N1 9GU. Registered in England No. 908396 |

|

|

|

|

|