The Fedâs aggressive response to the crisis: whatâs next?

The Federal Reserve responded aggressively to market dysfunction in March, shifting to an ultra-easy monetary policy and announcing emergency lender of last resort (LOLR) facilities under the section 13(3) power granted by the Federal Reserve Act of 1913.

The Fedâs timely and forceful initiatives effectively restored order to financial markets and lifted confidence. At the same time, the CARES Act increased deficit spending by $2.7 trillion or roughly 13% of GDP, including authorization to the Treasury to capitalize the Fedâs lending facilities. These expansive monetary and fiscal initiatives have provided income support to individuals and financial support to businesses to offset the pandemic and government shutdowns.

Today, the economic and financial environments are far different from when the Fed announced its emergency policies. Financial markets are functioning normally, the stock market has rebounded, and the economy is reopening and recovering.

While the Fed has recently slowed its asset purchases and some of its LOLR key asset purchases are scheduled to cease at the end of September, the Fed will face the tricky dilemma of how to unwind these programs without jarring markets. This will require carefully communicating the different roles of its basic monetary policy as distinguished from its emergency lender of last resort policies (LOLR). As the economy and financial markets continue to normalize, the emergency LOLR programs will no longer be appropriate and may impose costs and risks, and the Fed needs to establish and communicate a strategy for unwinding them.

This note first describes the characteristics of the financial collapse in March. It then details the Fedâs policy responses, including details of all Fed actions to date in the appendix, and includes a separate note on the surge in money supply. It then considers the issues the Fed faces in its eventual normalization of monetary policy.

The anatomy of Marchâs financial collapse

Certainly, the pandemic and government shutdowns were deeply serious once-in-a-lifetime events, but if portfolio managers perceived them to be temporary, why didnât cooler heads prevail, so that the stock market correction was more limited? Didnât they learn from the recovery from the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008-2009?

The real story is that amid the dramatic shift to extreme risk aversion and cash hoarding in anticipation of the spreading pandemic and government shutdown, there was forced selling into pockets of illiquidity that resulted in market dysfunction and accentuated the temporary collapse in valuations. This sequence of events also explains the intensity of the Fedâs responses.

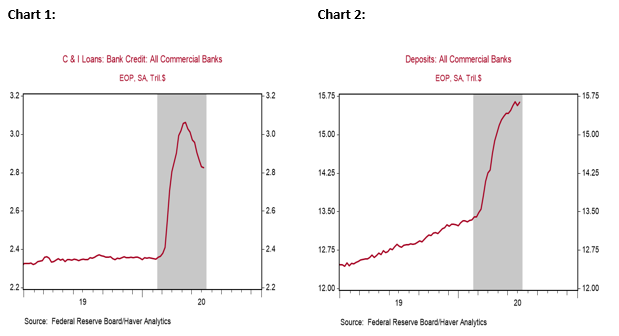

Anticipating that the government shutdown would halt their cash flows and concerned that banks would cut their lines of credit, many businesses drew down their unused lines of credit from banks, leaving the proceeds as deposits. This generated the biggest ever jumps in commercial and industrial (C&I) loans and bank deposits, as reflected in Charts 1 and 2. C&I loans soared 27% in an eight week period. This spike in C&I loans drove up banksâ risk-weighted assets, which for some banks, impinged on their capital adequacy ratios. In response, banks temporarily tightened other credit lines and took efforts to cut assets. Money center banks did so in part by cutting leverage to money managers and hedge funds, and tightening loan covenants.

This forced some money managers and hedge funds that were investing on leverage to sell stocks and bonds, similar to the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2008-2009. The forced selling into nervous, illiquid markets accentuated falling prices. The S&P 500 plunged 34% in four weeks. Bond yields, particularly on sub-investment grade bonds, spiked. The municipal bond market was temporarily unhinged by the liquidation of several large leveraged funds, and the spike in muni yields threatened the finances of state and local governments at the worst time (Chart 3).

Chart 3:

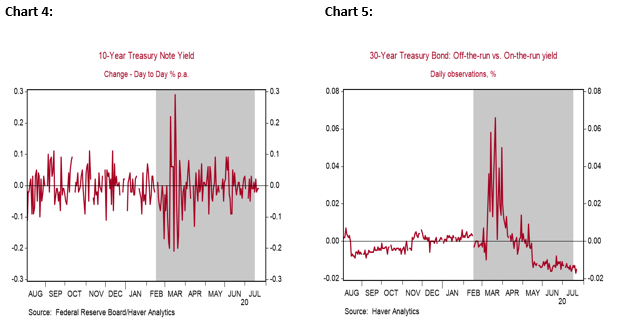

Most strikingly, the Treasury market, the worldâs most liquid market, experienced severe strains, including extreme swings in yields and divergent yields on Treasuries of similar maturities. During the six trading days between March 16 and 23, daily changes in 10-year Treasury bond yields averaged over 17 basis points, which from low yields represented extreme price changes (Charts 4 and 5). This dysfunction resulted from pressures on the balance sheets and capital of primary dealers in Treasury securities. (Darrell Duffie, âStill the worldâs safe haven? Redesigning the U.S. Treasury market after the COVID-19 crisisâ, The Brookings Institution, June 22, 2020). The dramatic increase in Treasury bond issuance to finance deficits and the temporary selling of Treasuries by cash hungry investors (largely foreign) bloated primary dealersâ balance sheets. This squeezed their cash and ballooned their borrowing needs. At the same time, some highly leveraged traders in the Treasury market were forced to unwind positions.

While the hits to the stock market and spikes in corporate bond yields were eye-catching (although much smaller in magnitude than during the GFC), the dysfunction in the Treasury bond market set off alarm bells at the Fed. The Fed responded quickly and forcefully.

The Fedâs responses

The Fedâs responses to the pandemic, government shutdown, and market dysfunction were much faster and more expansive than its responses to the GFC of 2008-2009. The Fed learned from the experiences of the GFC, and it vowed not to be tentative. Its interventions worked quickly to restore order to financial markets.

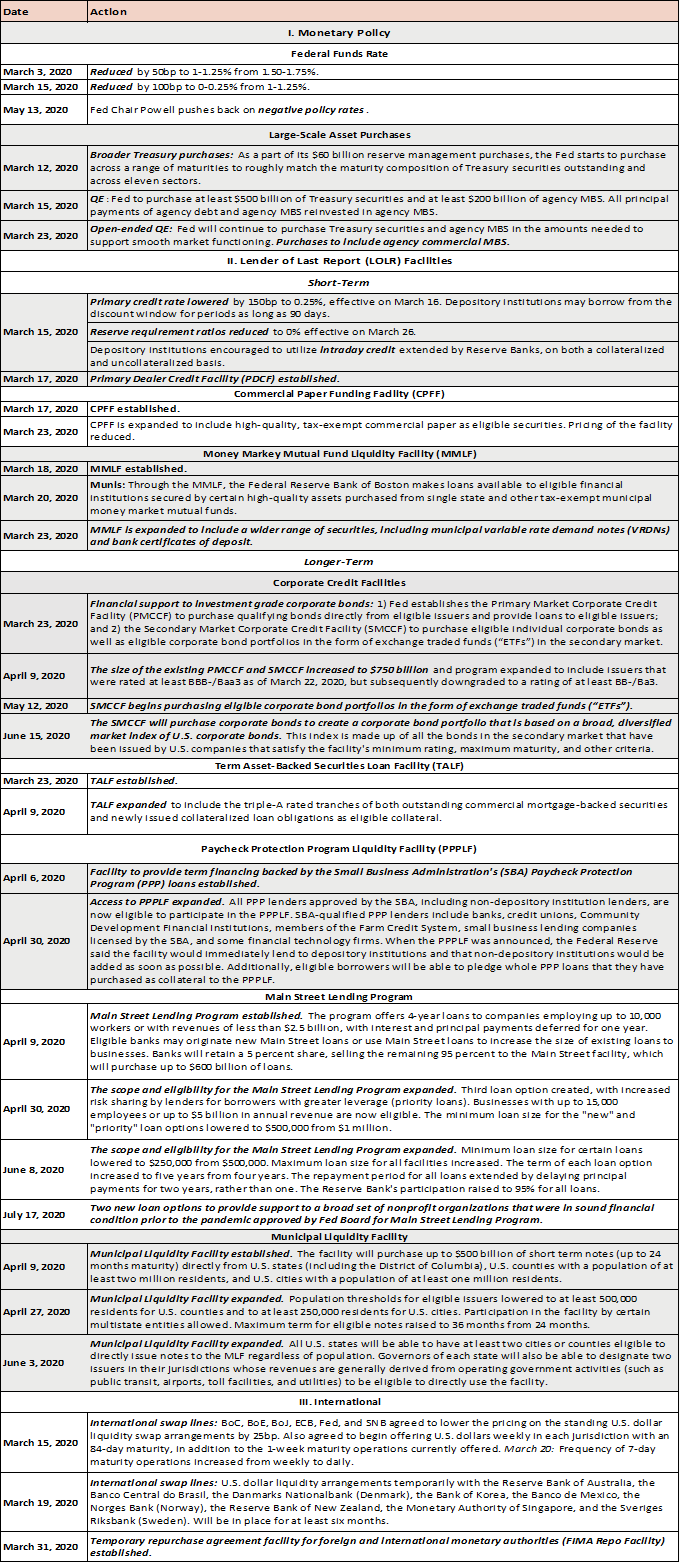

The Fedâs actions fall into two categories, monetary policies and lender of last resort (LOLR) policies. A summary of the Fedâs policy actions is provided in Appendix 1. Its monetary policies include interest rates and large-scale asset purchases (quantitative easing or QE) of Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities (MBS). The Fedâs LOLR facilities, conducted under the Fedâs section 13(3) powers, involve many of the short-run liquidity facilities used during the GFC, and newly established programs that involve purchases of longer duration credit and direct business lending.

In early March, as the implications of the COVID-19 pandemic became apparent and market distress intensified, the Fed cut its Fed funds rate target to zero and initiated modest QE of Treasuries. On March 15, amid government shutdowns, the Fed greatly expanded its QE of Treasuries and MBS. A couple of days later, it announced liquidity infusions into short-term funding markets, including the commercial paper market. The S&P500 fell 18.6% in the two weeks from March 9-23, following its 14.8% decline in the prior two weeks. Treasury markets were extremely volatile with pockets of illiquidity during March 16-23.

In direct response to the Treasury market dysfunction, the Fed bought over $1 trillion in Treasuries during a four-week period and extended loans to strained primary dealers. The Fed subsequently relaxed regulatory capital and cash ratio requirements on large bank holding companies. These actions brought relief to the Treasury market. Over the same period, the Fed purchased $256 billion MBS.

March 23 was the watershed day for the Fedâs aggressive policy responses and market dysfunction. The Fedâs announced package included unlimited purchases of Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities (MBS); the establishment of facilities to purchase corporate bonds of investment grade and bond Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs); and direct lending to eligible businesses. The Fed also re-instituted the TALF, the Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility originally established in response to the collapse in consumer lending in 2008. Several days later, on March 27, the CARES Act was enacted, which allocated roughly one-fifth of its spending authorization to the Treasury to capitalize the Fedâs lending facilities.

The announcement effects of the Fedâs policy intentions were powerful in lifting market expectations and confidence. The Fed provided only $4.3 billion into the commercial paper market, but CP yield spreads quickly narrowed to normal. Investors aggressively bought corporate bonds in anticipation of the Fedâs purchases of any corporate bonds. ABS spreads narrowed as investors anticipated the TALF program. Yields on Treasuries quickly fell and pockets of illiquidity dissipated.

The stock market began recovering quickly. In one week, it was up 17% from its trough, and after four weeks, it was up 26% (Chart 6). To date, the S&P500 has recovered roughly 86% of its peak-to-trough decline. Two factors have buoyed the stock market: expectations of economic recovery and the Fed--its aggressive policies and its forward guidance that it would maintain its expansive policies.

Chart 6:

In April, the Fed expanded its possible corporate bond purchase program to $750 billion and broadened the scope of its municipal debt purchases to include smaller municipalities. Based on the Treasuryâs financing authorization for the lending facilities and leverage, the Fed has flexibility to lend several trillion dollars directly to businesses, states, and municipalities.

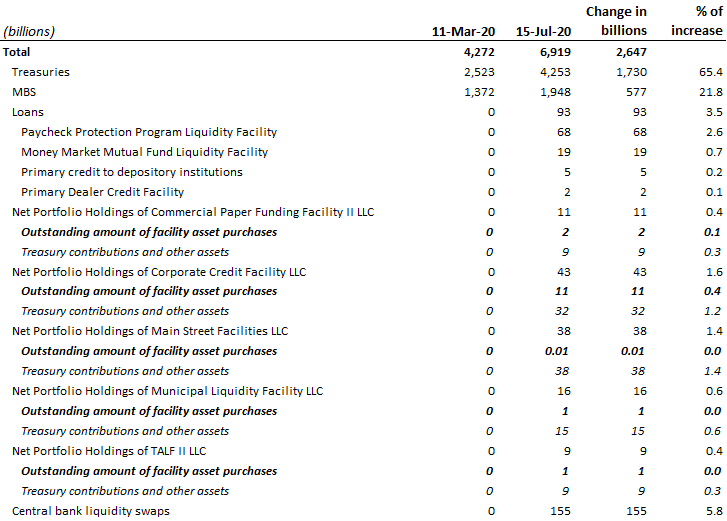

Through early June, the Fedâs balance sheet expanded from $4.2 trillion to $7.1 trillion, reflecting primarily its $1.6 trillion of purchases of Treasuries and $460 billion in purchases of MBS. The other large increase was the Fedâs liquidity swaps with foreign central banks, which peaked at $449 billion. The Fedâs other LOLR facilities have been implemented much more slowly and more modest in magnitude. Term financing to depository and non-depository institutions backed by Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loans through the Fedâs Paycheck Protection Program Liquidity Facility have amounted to $68 billion. To date, its Main Street Lending Program has been very small, with $12 million extended. This presumably reflects the covenants required on the lending program (Glenn Hubbard and Hal Scott, âMain Streetâ Program Is Too Stingy to Banks and Borrowers, The Wall Street Journal, July 20, 2020), which have reduced demand (the Fedâs capital losses in the lending programs are reimbursed by the Treasury.)

The Fed began purchasing corporate bond ETFs in May and individual corporate bonds in June. The total amount of corporate bond purchases has been a relatively modest $11 billion, the vast majority being ETFs. In keeping with its efforts to be fully transparent, on July 10, the Fed released a list of 297 separate companies that it has purchased bonds from June 18, 2020 through June 29, 2020.

Since mid-June, the Fedâs balance sheet has shrunk modestly. The biggest source of this decline has been the 65% reduction of its international swap lines. The Fed has slowed its purchases of Treasuries and MBS.

The surge in money supply

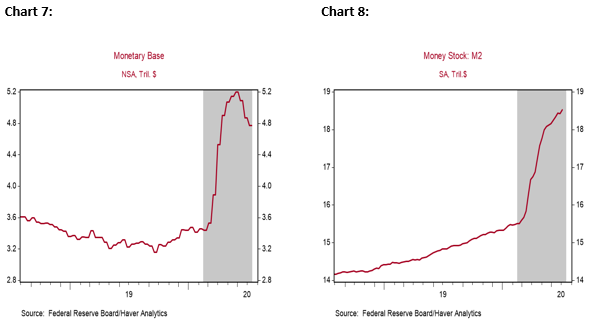

Reflecting the Fedâs massive asset purchases, cash hoarding and the impact of fiscal policy, money supply has surged faster than any time in modern history (Money supply spike: sources and implications, July 1, 2020). During the three months March-May, the monetary base (MB) which comprises bank reserves plus currency rose 49%, or 394% annualized, while M2, a broader monetary aggregate that includes primarily deposits, rose 16%, or 83% annualized (Charts 7 and 8).

The Fedâs purchases of Treasuries and MBS and its other infusions into financial markets have ballooned bank reserves. The vast majority of the reserves are in excess of reserves required by banks, a sizable portion of which are loaned back to the Fed. The Fed currently pays 10 basis points on those liabilities (it sets the IOER equal to the top of the 0%-0.25% Fed funds rate target minus 15 basis points).

The surge in M2 reflects cash hoarding and the spike in consumer and business bank deposits stemming from the governmentâs fiscal policy and constrained spending. In March, bank deposits surged 6%, as businesses drew down their lines of credit and left the proceeds as deposits. Deposits and M2 accelerated in April and rose again strongly in May, reflecting ongoing business cash hoarding plus the sharp jump in consumer deposits stemming from the government income support to individuals and financial support to businesses provided by the CARES Act.

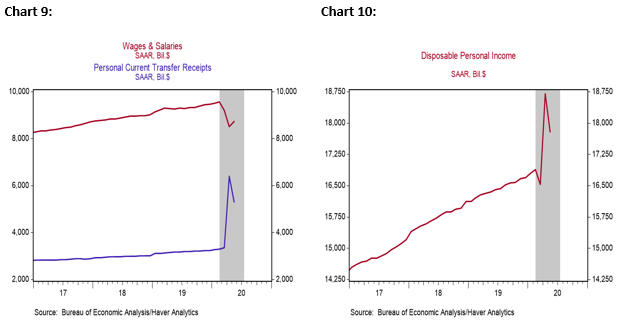

The government distributed $1,200 to individuals with incomes up to $75,000 (phasing out at $99,000) and $500 per child, totaling $300 billion, and approximately $144 billion in unemployment compensation in April and May, enhanced by an additional $600 per week. While cash-constrained recipients spent the government checks, a sizable portion of the government distributions was deposited in bank accounts. It is striking that during the fastest spike in unemployment in U.S. history, disposable income rose, as the increase in government transfer payments far exceeded the decline in wages and salary income (Charts 9 and 10). At the same time, the rate of personal saving soared to an all-time high as consumer and business spending was constrained by the pandemic and government shutdown. A portion of the estimated $525 billion of loans provided to businesses through the PPP was also deposited in banks.

The confluence of the simultaneous surge in the Fedâs monetary base and M2 and household savings will stimulate the economic recovery. A sizable portion of the surge in M2 will reverse as risk aversion abates and the savings are spent. This is true even if the rate of personal saving remains higher than its pre-pandemic level. Businesses have already begun to draw on their bank deposits to pay down their bank loans, and they will use cash reserves for operating expenses (Chart 1). Consumers have pent up demand and will spend a portion of their savings now held as deposits.

The Fedâs dilemma: getting back to a ânew normalâ monetary policy

Since March when the Fed initiated its emergency monetary and LOLR facilities, the situation has changed radically, and a new challenge looms on the Fedâs horizon. Financial markets are operating normally and there are clear signs the economy is recovering. Moreover, another very large fiscal stimulus package is in the pipeline (US fiscal policy issues on the horizon, July 13, 2020), which the Fed must consider since it has become a fiscal and credit agent of the Treasury.

Obviously, there is a tremendous amount of uncertainty about the economic outlook, and the Fedâs near-term goal is to support getting the economy back to normal and maintaining financial stability. If the economy backslides into recession, further monetary and lender of last resort support may be needed. But if the economy continues to recover as is expected, the Fed must balance the benefits of its current policies and the economic and political costs and risks of sustaining them.

The Fed needs to develop an intermediate-term strategy for judiciously unwinding its emergency LOLR policies while continuing to pursue an accommodative monetary policy that is consistent with its dual mandate of maximum employment and low inflation. Part of that strategy is largely built-in: simply allow short-term liquidity facilities to wind down as demand for them declines. In fact, as market stresses have dissipated, the demand for them have ebbed, and the Fedâs exposures have receded. The biggest decline has occurred in the Fedâs international swap lines, which have fallen from a high of $449 billion on May 27 to $155 billion on July 15 (Table 2, Appendix). The Fedâs lending to primary dealers has unwound from a peak of $33 billion on April 15 to $1.7 billion on July 15. The Fedâs liquidity infusion into the CP market has halved from $4.3 billion in mid-June to $2.1 billion in mid-July.

A second part of the Fedâs exit strategy was established when the Fed created its LOLR programs: on September 30 its purchases of corporate bonds (Secondary and Primary Corporate Lending Facilities, SMCLF and PMCLF), Main Street lending, and asset-backed securities (ABS) under its TALF program are scheduled to cease, while its Municipal Liquidity Facility is scheduled to cease on December 31. This however leaves an elongated transition period when the Fed would hold these longer duration credits (up to five years as the corporate bonds and the Main Street Loans mature, and three years when the Fedâs municipal debt and TALF-related holdings mature).

The largest portion of the Fedâs strategy is yet to be determined. Its massive asset purchases have generated the fastest growth in the monetary base in history and created trillions of dollars of excess reserves. That high-powered money will stay in the financial system until households and businesses spend itâthat is, it generates higher nominal GDPâor the Fed drains it out of the system.

In this context, the Fed must be strategic and forward-looking, in both an economic and political sense, and consider the impacts of its programs, and the desired bandwidth for monetary policy. It must ask tough questions about the benefits and potential costs and risks of extending and maintaining its holdings of longer- duration corporate bonds, municipal debt and ABS, and what to do with its massive holdings of Treasuries and MBS. Complicating the Fedâs task is the strong impact the Fedâs forward guidance has on financial markets and confidence. The Fed fully understands how expectations play an important role in influencing financial markets and the economy. It remembers its rocky attempts to unwind policies following the GFC, and does not want to do anything or provide forward guidance that may be jarring.

The Fed needs to establish closure on its short-term liquidity facilities on a timely basis, as it did for its LOLR programs following the GFC. Doing so would establish these programs as emergency facilities that are part of the Fedâs toolkit for crises, but not available during normal times. Demand for these facilities have subsided, so announcing closure should not be a surprise to markets.

The Fedâs $11.5 billion purchases of corporate bonds and bond ETFs through July 15 have been very small relative to both the Fedâs purchases of Treasuries and MBS and total outstanding nonfinancial corporate debt ($17 trillion). It seems that the largest impacts of the Fedâs corporate bond purchase programs have been the announcement effects of the Fedâs intentions on market expectations, rather than the outright purchases. These effects have provided large benefits to the corporate bond marketâlower yields and more liquidityâand directly to large businessesâeasier funding. However, it is doubtful that these effects have stimulated business investment, and uncertain whether they have raised employment. Moreover, it highlights the importance of the Fedâs forward guidance, and how much financial markets crave Fed support.

While the Fed faces no financial risks in these bond purchases (Congress established this program in the CARES Act, and the Treasury reimburses the Fed for any losses it incurs), there are other risks. Purchasing corporate bonds necessarily involves picking winners and losers among companies and business sectors. Such direct involvement in traditional credit and fiscal policies exposes the Fed to the whims of politics, jeopardizing its independence, particularly in todayâs highly contentious political and social environment. For example, how does the Fed respond to allegations that it is subsidizing big business, while private firms face much more severe cash flow problems and do not have adequate access to debt? What if the Fed purchases bonds in a corporation whose behavior is found to be inconsistent with todayâs social norms? While the Fed is striving to be transparent, public perceptions matter, and the Fed may find that they are hard to manage.

While providing financial support to businesses to cope with the pandemic and government shutdown is entirely appropriate, a better approach would have been for the Treasury to manage the bond purchase program. Now that the Fed is managing it on behalf of the Treasury and Congress, however, it should establish a strategy for how to unwind it on a timely basis, depending on the circumstances. One logical strategy would be for the Fed to swap its corporate bond holdings with the Treasury for Treasury securities of similar duration. This would end the Fedâs exposures to corporate credit while avoiding any negative announcement effect of outright selling the positions.

The Fedâs holdings of municipal debt securities are also relatively smallâ$1.2 billionâbut they potentially involve political risks. What are the political ramifications of the Fed providing direct financial support to some municipalities, but not others? The fiscal legislation under consideration by Congress and the Administration will involve Federal financial support to states. States face huge financing gaps, and the Federal government is in a better position than states to borrow. The issues involved in state financing and the municipal bond market are inherently fiscal in nature and the Fed would be wise to not use its monetary powers to address such thorny issues.

The Fed has just begun to purchase ABS under its TALF, and the amount to date is very small, $937 million through July 15, but it should consider whether continuing such a program is even appropriate. Following an initial spike in ABS yields that was small compared to 2008-2009, yield spreads quickly fell back to pre-pandemic levels. Moreover, unlike the GFC, consumer credit is readily available. Lowering ABS spreads further through Fed purchases would not help reduce the debt service costs of current household debtors.

This leaves the Fedâs massive holdings of Treasuries and MBS. With $4.25 trillion in Treasuries, the Fed is the largest holder in the world, with a 21% share. Its $1.95 trillion holdings of MBS represents 12% of all mortgage debt outstanding. A critical issue is the purpose they serve as the economy returns to normalâthat is, their economic impacts. Excess reserves in the banking system total $2.8 trillion. Yields on 10-year Treasuries remain below 0.7%, despite a drift up in inflationary expectations and clear signs the real economy is recovering. The conventional mortgage rate is below 3%, an historic low, clearly stimulating mortgage and housing activities. Many loan contracts in the private sector are based on short term funding costs (LIBOR) that are anchored to the Fedâs 0% policy rate, not bond yields, and the Fed intends to keep it there.

What balance sheet strategy would be consistent with the Fedâs dual mandate? The Fed is most likely to postpone addressing this issue. The Fedâs most likely path will be to maintain its far-oversized balance sheet, keep rates at zero, and establish that its 2% inflation target is an average, clearly signaling that it would allowâand actually preferâinflation to rise (temporarily) above 2%. From its muddled exit from its emergency monetary policies of the GFC, the Fed wants to avoid any controversy, particularly in todayâs charged political environment.

What is interesting is whether the Fedâs massive balance sheet actually stimulates economic activity. Its massive QE asset purchases following the GFC (QEII and QEIII) did not generate any acceleration in nominal GDP, so inflation remained below the Fedâs 2% target. In a sense, the Fedâs great balance sheet expansion âworked because it didnât workâ. If its post-crisis QEs had actually stimulated the economy as the Fedâs models had predicted, the economy would have boomed and inflation would have risen materially, and the Fed would have been forced to raise rates and unwind its balance sheet. That did not happen, so the Fed is willing to play the same angle today. (The Fed has become adapt at Washington politics: if there is not a sustained acceleration in nominal GDP, the Fed will say that if it had not maintained such a large balance sheet, economic and labor market conditions would have been much worse; if the economy accelerates and inflation rises, the Fed will take credit for the improvement.)

Such a strategy would send a clear signal. It would provide support to the stock market; favor mortgage financing and housing activity; and be consistent with a lower U.S. dollar (Chart of the week â A weaker U.S. dollar: big implications, June 5, 2020). For fiscal policy, it would constrain the costs of debt service and support deficit spending, and submit the Fed to fiscal dominance. This could prove to be a risky and costly strategy, on several dimensions.

APPENDIX

Table 1: Fed's policy actions in response to COVID-19 crisis

Source: Federal Reserve Board and Berenberg Capital Markets

Table 2: Change in Fed's balance sheet since mid-March

Source: Federal Reserve Board and Berenberg Capital Markets

Mickey Levy, mickey.levy@berenberg-us.com