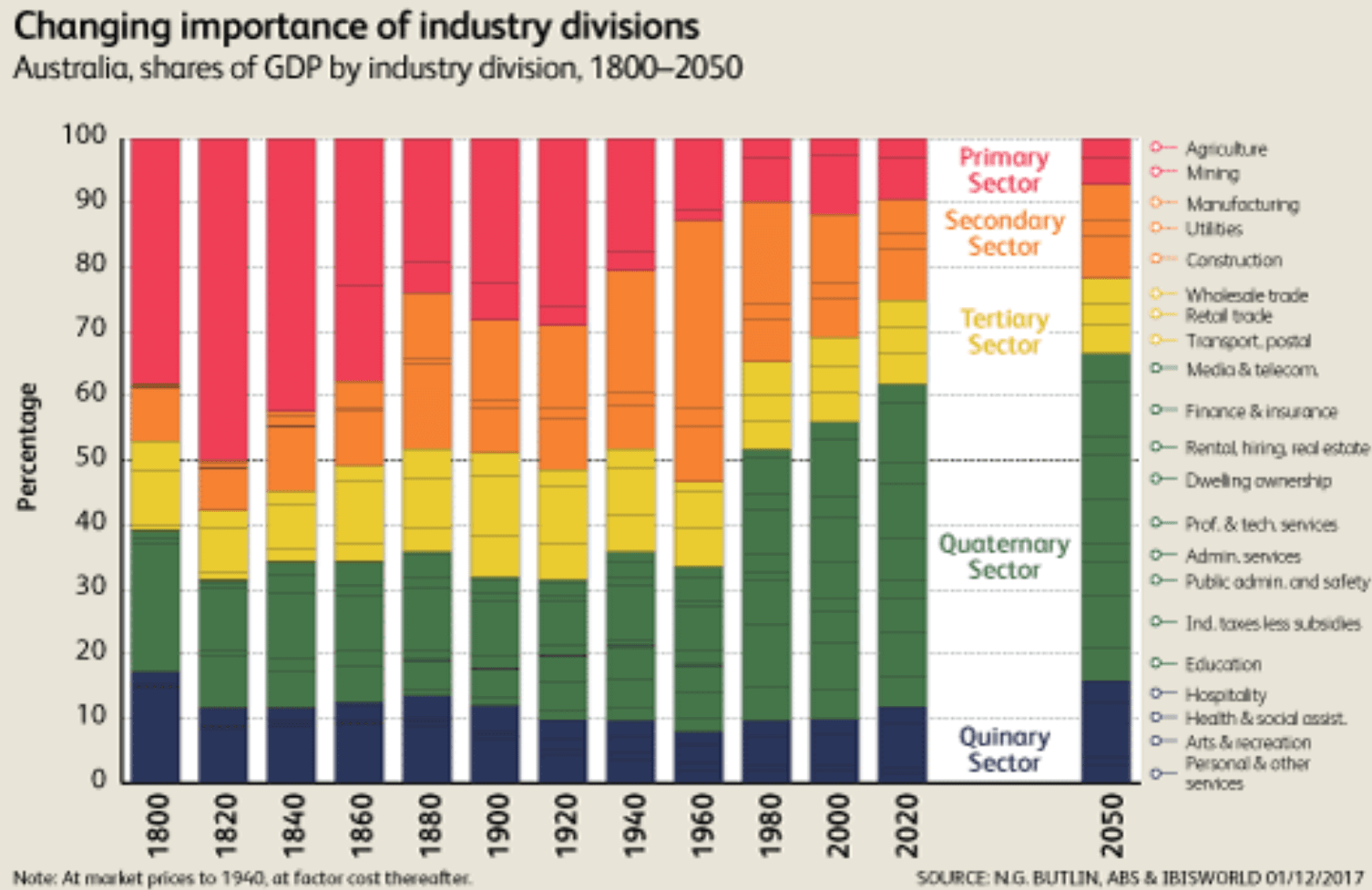

| Ditching the mineral myth Discretionary spending is far more important to the Australian economy than the resources we send to China and elsewhere. But few people understand this. Most Aussies continue to overestimate the role commodities play in the Australian economy. The news constantly bombards us with how much copper, nickel or iron ore is leaving our shores. Raw minerals make up 45% of total Aussie exports. Throw in agricultural exports and you’re looking at two sectors responsible for 57% of exports based on value. That leads many to believe we’re an exporting nation. But we’re not. Minerals and agricultural products may dominate what leaves shipping ports yet, combined, they make up less than 10% of our total income. Take a look… Aussie industry contributions to GDP  Source: IBISWorld Yes, exports once dominated the economy…a lazy century ago. Today, Australia’s considered a mixed-market economy. We draw our income from four key sectors: minerals, agricultural, manufacturing and services. The upside is that this diversity provides the economy with a buffer in tougher times. In fact, these sectors have enabled Australia to weather every sector downturn for the past 27 years. As the chart above shows, the amount that raw minerals and agriculture contribute to GDP falls each decade. So much so that, over the past 40 years, the Australian economy has reshaped itself to become a services economy. Of the $1.7 trillion in GDP produced last year, 55% came from services. Yet raw minerals and agriculture accounted for less than one-fifth of consumption. This is where the problem begins… The path to continuous economic growth To highlight the problem with this, we first need to take a step back. How did Australia ditch the exporting economy and become a services based one? Several decisions the Australian government made in the 1980s opened the economy to international trade. Tariffs were slowly reduced on many imported goods. And local manufacturing gradually lost the ability to compete with factories in China. As less trade and labour skills were needed, more teenagers opted to attend university, creating an intellectual cohort the magnitude of which Australia had never seen before. Meanwhile, the Hawke government floated the Aussie dollar. That allowed the market — and not the government — to decide the value of the dollar. Over the same period, households shifted. More families switched from single to dual income. In 1984, only 17% of Aussie households had two full-time wage earners — compared to 25% today. The biggest difference here though is that, in 1984, 50% of Aussie families had one stay-at-home parent. Today, it’s around 30%. Additional income has no doubt fuelled our ability to buy things and grow our services based economy. Combined, these factors transformed Australia into a consumerist society. After the 1991 recession, the political decisions of the 1980s filtered through, allowing the Aussie economy to flourish. As we came out of the recession ‘we had to have’, falling interest rates and tweaks to bank lending standards allowed Aussies to buy investment homes. From there, it was a series of great escapes. The dotcom market crash in the US was a blip in Australia…mostly because of our non-existent tech sector. Similarly, in 2008, when the US market was crippled once again, China swooped in, bartered for our rocks and propped up the Aussie economy once more. Over almost three decades, every time we should’ve entered a recession, there was a knight in shining armour. Yet every single step — whether it be the sudden rise in the value of iron ore, the change in Aussie households making money, or the lowering of interest rates — created an entire generation that has never seen a recession. The crutch of the economy The ugly truth is that most Australians have forgotten what a recession looks like, if they’ve ever known one at all. We have become so used to spending as we like that I’ll wager even economic experts don’t know where spending will be cut first… The morning latte on the way to work? Or the modern ‘essentials’ like Netflix, Spotify or Foxtel? These are the little things. The small, innocuous purchases people in a thriving economy wouldn’t think twice about. Every time an apparel store closes in a shopping strip, a café, specialised goods dealer or some form of niche physical training business takes its place. These insignificant items make up the discretionary spending that fuels the Aussie economy. All told, Australia’s discretionary spending is frittered away on feel-good purchases. Items we know we can buy because we feel rich. How would that change in times of recession? What spending will the average Aussie give up first…and last? And just how devastating will the impact be to the people and businesses that serve and sell us things? Ultimately, consumption is our way of life. It has supported economic growth for the past 27 years. That record-breaking run is likely to end sooner rather than later. And when it does, it will be a real wake-up call for most. | Kind regards, |  | | Shae Russell,

Editor, The Daily Reckoning Australia |

PS: Any recession in Australia will likely have devastating consequences on the majority of households across the nation. With sky-high household debt, rising inflation, meagre wage growth and no obvious saviour to export our way out of trouble to, any hopes of a soft landing have been all but dashed. Which is why every Australian, regardless of their wealth, should start preparing for such an outcome well in advance of its arrival. Doing so could be the difference between thriving during recession and seeing your wealth go up in smoke. How is it possible to prosper during a time of financial hardship? You’ll find everything you need to know here. |