|

|

The Writer's Almanac from Friday, September 27, 2013

The text of this poem is no longer available.

"August" by Mary Oliver, from New and Selected Poems: Volume Two. © Beacon Press, 2007.

Today is the birthday of Scottish writer Irvine Welsh, born in Leith, Edinburgh, in 1958. He's best known for his first novel, Trainspotting, which became a cult hit after it was published in 1993. A few years later, the book was adapted into a movie directed by Danny Boyle and starring Ewan McGregor. By the end of the decade, Irvine Welsh was one of Scotland's highest-earning writers.

Welsh grew up in the Leith, Edinburgh, housing projects, hanging out with folks who used their dole money to support their heroin addictions. He trained as a TV repairman, but after receiving a big electrical jolt, he decided to quit. He moved to London, joined the punk scene, played guitar in some bands, and was arrested for a bunch of different petty crimes. After one judge decided to suspend Welsh's sentence rather than making him serve, Welsh decided he'd take the chance to reform his ways.

He enrolled in a computer skills program, worked in real estate, and completed an MBA degree. And he found an old diary of his, from 1982, about druggie life in the Edinburgh projects. His diary, along with a journal full of notes he'd taken on a Greyhound bus ride from Los Angeles to New York, became the basis for his book Trainspotting. It's full of obscene language and vulgarity, and many critics found it offensive, but the book was still longlisted for the Booker Prize. And it was a huge best-seller.

Welsh is also the author of the novels Marabou Stork Nightmares (1995), Filth (1998), and The Bedroom Secrets of the Master Chefs (2006). His most recent novel is Skagboys (2012).

It's the birthday of writer Joyce Johnson, born Joyce Glassman in New York City (1935). She ran away to Greenwich Village when she was still a teenager, and got to know people at the center of the emerging Beat Generation. Her troubled, two-year affair with Jack Kerouac is recounted in her memoir Minor Characters, A Young Woman's Coming of Age in the Beat Orbit of Jack Kerouac (1999), which won a National Book Critics Circle Award. She has also published Doors Wide Open: A Beat Love Affair in Letters 1957-1958, the letters she and Kerouac exchanged during their relationship.

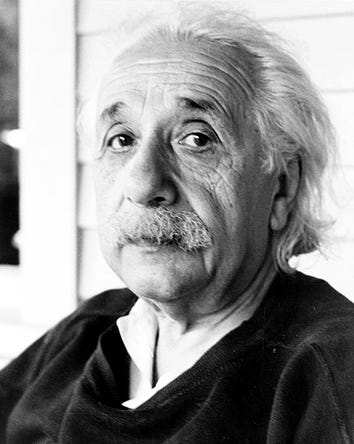

And it is the birthday of one of science's most famous equations: E = mc².

1905 was a banner year for Albert Einstein: his annus mirabilis. It was the year he completed his doctoral thesis: "A new determination of molecular dimensions." And he also published four groundbreaking papers in the prestigious German journal Annalen der Physik (Annals of Physics). In March, he submitted a paper that proved that light could behave as a particle as well as a wave, and gave rise to quantum theory ("On a heuristic point of view concerning the production and transformation of light"). In May, he used Brownian motion — the irregular movement of small but visible particles suspended in a liquid or gas — to prove empirically that atoms exist. In June, in his paper "On the electrodynamics of moving bodies," he laid out his theory of Special Relativity, which deals with the way the speed of light affects the measurement of time and space.

And on September 27, 1905, he submitted a paper that asked, "Does an object's inertia depend on its energy content?" He used the equation E = mc2 (energy equals mass times the speed of light squared) to reveal that matter and energy are deeply connected. In the course of working through his theory of Special Relativity, his calculations led him to a surprising insight: if an object emits energy, the object's mass must decrease by a proportionate amount. Einstein wrote to a friend, "This thought is amusing and infectious, but I cannot possibly know whether the good Lord does not laugh at it and has led me up the garden path." In a 1948 film called Atomic Physics, he explained, "It followed from the special theory of relativity that mass and energy are both but different manifestations of the same thing — a somewhat unfamiliar conception for the average mind." Physicist and mathematician Brian Greene explains it to the average 21st-century mind this way, in a 2005 op-ed piece for The New York Times: "When you drive your car, E = mc2 is at work. As the engine burns gasoline to produce energy in the form of motion, it does so by converting some of the gasoline's mass into energy, in accord with Einstein's formula."

Einstein's equation also led to the discovery that a small amount of mass can be converted into a large amount of energy. This discovery eventually led to the development of nuclear energy — and the atomic bomb — when scientists found a way to harness the energy that binds atoms together. As Brian Greene explains, "A little bit of mass can thus yield enormous energy. The destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki was fueled by converting less than an ounce of matter into energy; the energy consumed by New York City in a month is less than that contained in the newspaper you're holding." Splitting apart the nucleus of an atom releases that binding energy and causes a chain reaction to spread throughout the nuclei of nearby atoms. Einstein's theory didn't tell scientists how to do this, but it did give them a measurement tool to determine which types of atoms had the strongest bonds and therefore the most potential energy.

On the centenary of Einstein's annus mirabilis, to honor his achievements, the United Nations declared 2005 the International Year of Physics. And to celebrate the 100th birthday of E = mc2, a group of physicists used 21st-century technology to put Einstein's theory to the test. They measured the mass of radioactive atoms before and after the atoms emitted gamma radiation, and they also measured the energy contained in the gamma rays. They plugged the numbers into Einstein's famous equation and found that it was accurate within four hundred thousandths of one percent.

Be well, do good work, and keep in touch.®

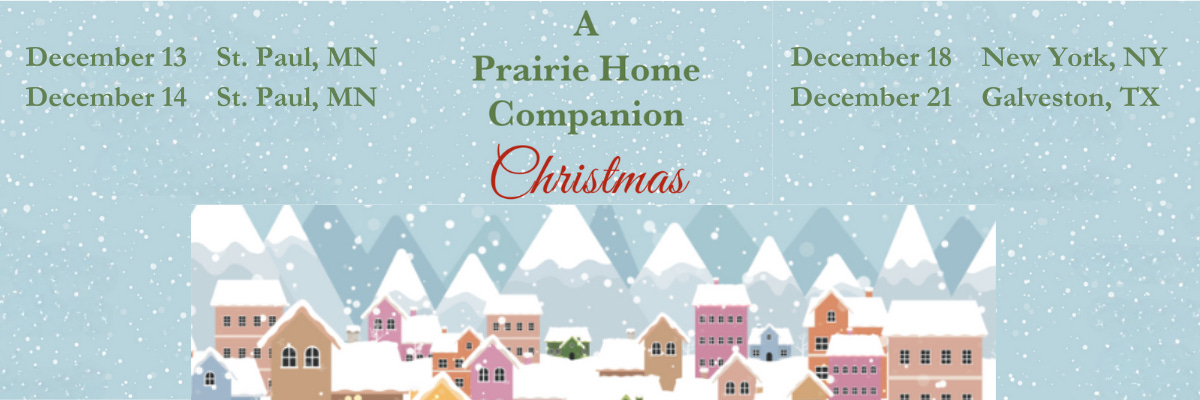

If you are a paid subscriber to The Writer's Almanac with Garrison Keillor, thank you! Your financial support is used to maintain these newsletters, websites, and archive. If you’re not yet a paid subscriber and would like to become one, support can be made through our garrisonkeillor.com store, by check to Prairie Home Productions, P.O. Box 2090, Minneapolis, MN 55402, or by clicking the SUBSCRIBE button. This financial support is not tax deductible.