|

|

The Writer's Almanac from Monday, April 15, 2013

"The Undeniable Pressure of Existence" by Patricia Fargnoli, from Duties of the Spirit. © Tupelo Press, 2005.

ORIGINAL TEXT AND AUDIO - 2013

Today is Tax Day. The federal income tax has been in effect since Congress ratified the 16th Amendment in 1913. That first year, the form was only two pages long. Humorist Dave Barry wrote, "It's income tax time again, Americans: time to gather up those receipts, get out those tax forms, sharpen up that pencil, and stab yourself in the aorta."

It's the birthday of humorist and biographer Morris Bishop, born in Willard, New York (1893). His dad was a doctor, and Morris Bishop was born at the Willard State Hospital for the Insane, where his father and grandfather worked.

He studied Romance languages at Cornell and then became a full-time professor there, and he stayed at Cornell for the rest of his career. He was a brilliant scholar, fluent in German, Swedish, French, Spanish, Latin, and modern Greek. He wrote biographies of Pascal, Champlain, La Rochefoucauld, Petrarch, and St. Francis. But we remember him best as the author of light verse, such as this:

I lately lost a preposition:

It hid, I thought, beneath my chair.

And angrily I cried: "Perdition!

Up from out of in under there!"

Correctness is my vade mecum,

And straggling phrases I abhor;

And yet I wondered: "What should he come

Up from out of in under for?"

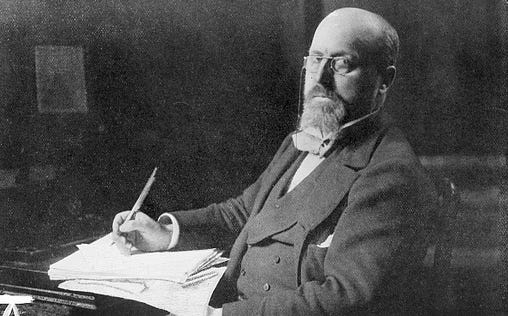

It's the birthday of Henry James, author of 20 novels, 112 stories, 12 plays, and several books of travel and criticism, born in New York City (1843). His father was a friend of Thoreau, Emerson, and Hawthorne, and the family traveled throughout Europe. When James was in his 20s and writing short stories, he moved to Europe because he could live cheaply there and felt at home as an outsider. Then he fell in love with England. He wrote, "The capital of the human race happens to be British." James wrote the majority of his famous novels — like The Portrait of a Lady (1881) and The Wings of the Dove (1902) — and his famous stories — like "The Turn of the Screw" (1898) — either in London or an old house in Sussex, near the ocean.

Although James was the toast of London's literary society for much of his career, he really wished to be a dramatist. But one of his plays was poorly received and James himself was booed on opening night and that discouraged him.

James never managed to make much money or wide acclaim from his writing. It didn't bother him, but it did his friend Edith Wharton. Toward the end of James' life, she lobbied for him to win the Nobel Prize, to no avail, and was in the midst of taking up a collection from his New York friends, intending to send him a 70th birthday present of cash, when he discovered her plot and intervened. But he never knew that one of his final book advances, for a novel that was still incomplete when he died, came from Wharton's own coffers. She'd proposed the scheme to his publisher, Charles Scribner, who wrote James out of the blue with the offer of $8,000 for a new book, a sum far greater than James' previous advances. James accepted, none the wiser. Scribner felt uncomfortable about it: "I feel rather mean and caddish and must continue so to the end of my days," he wrote to Wharton. "Please never give me away." She didn't; their secret was only discovered years later in Scribner's and Wharton's archives.

Be well, do good work, and keep in touch.®

Serenity at 70, Gaiety at 80: Why you should keep on getting older by Garrison Keillor

Created just for fans as a keepsake from Garrison and available only in our store this wonderful gem on aging will tickle your funny bone!

If you are a paid subscriber to The Writer's Almanac with Garrison Keillor, thank you! Your financial support is used to maintain these newsletters, websites, and archive. If you’re not yet a paid subscriber and would like to become one, support can be made through our garrisonkeillor.com store, by check to Prairie Home Productions, P.O. Box 2090, Minneapolis, MN 55402, or by clicking the SUBSCRIBE button. This financial support is not tax deductible.