|

|

The Writer's Almanac from Monday, September 25, 2017

“Peonies” by Jim Harrison from In Search of Small Gods. © Copper Canyon Press, 2010.

ORIGINAL TEXT AND AUDIO - 2017

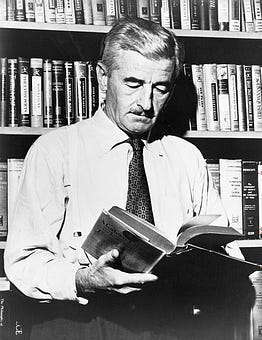

It’s the birthday of American novelist William Faulkner (1897), who once said, “If I had not existed, someone else would have written me.” Faulkner is best known for his long, lyrical, and often violent novels that explore Southern culture and history, like Absalom, Absalom! (1936), As I Lay Dying (1930), and The Sound and the Fury (1929). When President John F. Kennedy invited Faulkner, then teaching in Charlottesville, Virginia, to dine at the White House with other Nobel Prize laureates, Faulkner famously declined, saying, “Why, that’s a hundred miles away. That’s a long way to go just to eat.”

Faulkner was raised in Oxford, Mississippi, where he would spend most of the rest of his life, and was a voracious reader, though he didn’t do well in his studies, and never graduated his local high school. He enrolled as a special student at Ole Miss and worked as the postmaster at the university station, but was fired for reading on the job. A girl broke his heart, so he enlisted in the Royal Air Force, hoping to fight in World War I, and added a ‘u’ to his name to seem more English, but he never saw action. The war ended while he was in training in Toronto. Faulkner married that same girl several years later. He once famously claimed that he removed the doorknob to his writing room so his kids couldn’t get in while he was working.

His first few books, like Sartoris (1929) and As I Lay Dying (1930), didn’t make any money, so he wrote a book called Sanctuary (1931), which was a kind of potboiler, and a little salacious, and it was a hit.

William Faulkner wasn’t well known when he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1949. Most of his best works were already far behind him, like The Sound and the Fury, which focuses on several generations of the Compson family. The book takes its title from a line in Shakespeare’s Macbeth. Faulkner once called it “a splendid failure.” He said: “When I began the book, I had no plan at all. I wasn’t even writing a book. Previous to it I had written three novels, with progressively decreasing ease and pleasure, and reward or emolument. … One day it suddenly seemed as if a door had clapped silently and forever to between me and all publishers’ addresses and booklists and I said to myself, Now I can write. Now I can just write.”

Faulkner was famously snippy, and had a long feud with Ernest Hemingway, which started when Faulkner said: “Ernest Hemingway: he has no courage, has never crawled out on a limb. He has never been known to use a word that might cause the reader to check with a dictionary to see if it is properly used.” Hemingway retorted: “Poor Faulkner. Does he really think big emotions come from big words?” When an editor asked Faulkner if Hemingway should write a preface to Faulkner’s new collection, Faulkner spat: “It seems to me in bad taste to ask him to write a preface to my book. It’s like asking one race horse in the middle of a race to broadcast a blurb on another horse in the same running field.”

The Guinness Book of World Records lists Faulkner’s novel Absalom, Absalom! as having the longest single sentence in literature. It’s in chapter six.

When he was asked about writer’s block, William Faulkner answered: “I have no patience; I don’t hold with the mute inglorious Miltons. I think if he’s demon-driven with something to be said, then he’s going to write it. He can blame the fact that he’s not turning out work on lots of things. I’ve heard people say, ‘Well, if I were not married and had children, I would be a writer.’ I’ve heard people say, ‘If I could just stop doing this, I would be a writer.’ I don’t believe that. I think if you’re going to write you’re going to write, and nothing will stop you.”

He added, “If a writer has to rob his mother, he will not hesitate; the ‘Ode on a Grecian Urn’ is worth any number of old ladies.”

It was on this day in 1957 that nine black teenagers, six girls and three boys, entered Central High School in Little Rock, Arkansas, escorted by members of the U.S. Army’s 101st Airborne Division.

At the time, Little Rock was considered a relatively liberal southern city. There was no segregation on buses or in libraries or parks. But schools were still segregated three years after the Brown v. Board of Education decision mandating integrated classrooms. Teachers at the all-black schools began handing out applications to attend the all-white Central High School, considered one of the best high schools in the state. The list of applicants was narrowed down to 17 of the very best black students in the district, and eight of those changed their mind at the last minute, leaving nine students total. They became known as the Little Rock Nine.

One of those students, Minnijean Brown, remembers picking out her best outfit for the first day of classes that year. She wasn’t too worried. She said, “I figured, ‘I’m a nice person. Once they get to know me, they’ll see I’m OK. We’ll be friends.’” But Little Rock Nine never even got close to the school building that first day. A mob of segregationist white students and parents surrounded the school.

One of the nine students was chased by the mob until a white woman helped her onto a city bus. The nine black students tried twice to enter the building, and each time the crowd grew more threatening, shouting obscenities and spitting at the students. Elizabeth Eckford said that when she got home she was able to wring the spittle from her dress.

The second failed attempt to enter the school was captured by television cameras, and Americans across the country were shocked to see how these nine students were being treated not only by a racist mob but also by the Arkansas National Guard, who had been ordered to prevent their entry by the Arkansas governor, Orval Faubus.

So on this day in 1957, President Dwight D. Eisenhower sent 1,000 troops from the 101st Airborne Division to escort the students up the front steps and into their classrooms. The students were shown on national television walking into the school, with stern looks on their faces, their heads held high, as the mob stood all around them.

The 101st Airborne Division remained in the school for the rest of the year, but the nine students were still subjected to taunts and humiliation. One of the girls said that she never went to the bathroom at school her entire first year, because the soldiers who would have protected her couldn’t accompany her, and it would have been too dangerous. One of the nine had acid thrown in her face. Another was cut with broken glass. Another was kicked down the stairs. Their families received death threats.

After the experience of that school year, most of the nine tried to keep a low profile. Only one of them became a civil rights activist. The others became an accountant, a corporate vice president, a social worker, a real estate agent, a psychologist, a teacher; two became homemakers. Most of them didn’t even tell their children what they’d gone through. Their children had to find out about it in history class. All nine of them were awarded the Congressional Gold Medal in 1998.

Be well, do good work, and keep in touch.®

CLICK HERE to order Boom Town by Garrison Keillor

You’re a free subscriber to The Writer's Almanac with Garrison Keillor. Your financial support is used to maintain these newsletters, websites, and archive. Support can be made through our garrisonkeillor.com store, by check to Prairie Home Productions P.O. Box 2090, Minneapolis, MN 55402, or by clicking the SUBSCRIBE button. This financial support is not tax deductible.