|

|

The Writer's Almanac from Sunday, September 15, 2013

"In Paris with You" by James Fenton, from Yellow Tulips. © Faber and Faber, 2012.

ORIGINAL TEXT AND AUDIO - 2013

On this day in 2008, the Wall Street investment firm Lehman Brothers filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, causing the S&P to lose more than 500 points by day's end, and costing its 26,000 employees their jobs. Lehman's collapse was the largest bankruptcy in world history. Investors, including the pension funds of many middle income Americans, saw Lehman's stock plummet 96 percent by the close of the day. One of only five investment banks on Wall Street, Lehman was a 158-year-old storied institution that had survived all manner of economic crisis, including the great railroad bankruptcies of the 1800s. As technology made trading stock easier, it became less profitable for large banks, and Lehman sought out riskier and riskier investments. They bought up large bundles of mortgages in a housing market that in recent years had seen a doubling and tripling of home values. A large number of these were subprime mortgages, sold to homeowners and investors that should have never been approved, and were unable to pay them back, making them virtually worthless.

Just months earlier, as the housing crisis was beginning to unravel, the federal government had stepped in and helped save banking giant Bear Stearns from bankruptcy on fears that it was "too big to fail." It had done the same for mortgage lenders Fannie and Freddie Mac. When Lehman Brothers began to sink, it too asked for a federal bailout, but the Feds declined, saying that there was no prospective buyer — there had to be an end to the bailouts — and hoping the economy could withstand the jolt.

Despite the very real possibility that Lehman's collapse could start a chain reaction crashing the world economy, Lehman successfully entered bankruptcy and began years of selling off its more than $600 billion in assets in an attempt to pay off its creditors. Lehman's holdings were so enormous that this task alone is expected to take beyond the year 2016.

It's the birthday of the first best-selling American novelist, James Fenimore Cooper, born in Burlington, New Jersey (1789). For most of his life he was known as James Cooper, but after his father's death, he tried to have his name legally changed to Fenimore, so as to inherit some property from his mother's family. He didn't get the property, but the name stuck.

He started out as a Navy man, but after he got married, his wife persuaded him to quit the sea and stay home. He struggled to run the estate he had inherited from his father, and he got into terrible debt. One day, he was reading aloud to his wife from an English novel, and he said he thought he could write a better novel himself. His wife laughed at him, because he didn't even enjoy writing letters much, but he sat down and wrote a book and it was published as Precaution (1820). He wrote six novels in the next six years.

He became best known for his series of five novels called the Leatherstocking Tales, including Last of the Mohicans (1826), about frontier violence and adventure. At the time, most Americans read English literature about kings and queens, because they thought it was more romantic than their own difficult, colonial lives. James Fenimore Cooper was the first American author to make the wild, untamed life in America seem romantic.

During his life, he was widely respected as a great novelist, but after his death, Mark Twain wrote an essay called "Fenimore Cooper's Literary Offences" (1895) that helped to destroy his reputation. Twain wrote:"[The rules of literature] require that the personages in a tale shall be alive, except in the case of corpses, and that always the reader shall be able to tell the corpses from the others. But this detail has often been overlooked in [Cooper's books]." But Fenimore Cooper is still remembered for making America a subject for adventure and romance.

It's the birthday of humorist, actor, and drama critic Robert Benchley (1889), born in Worcester, Massachusetts. He became managing editor of Vanity Fair in 1919, and that was where he met Dorothy Parker and Robert Sherwood. The three of them would go to lunch together at the Algonquin Hotel and complain about their jobs, and those sessions formed the core of what would become the Algonquin Round Table. He was only with Vanity Fair briefly, because Parker was fired in January 1920, and he and Sherwood resigned in protest. He was hired by Life magazine a few months later, and worked as a drama critic for about nine years. He was also a regular contributor to The New Yorker during that time, and in 1921, he published his first essay collection, Of All Things!

Benchley also wrote and acted in several short films from the late 1920s onward, usually humorous monologues. Through the 1930s and into the '40s, he gradually moved away from writing, becoming more and more interested in films, but all his work carried the same thread of the self-deprecating and mildly inept intellectual. By 1943, he had given up writing. And in 1945, he died of cirrhosis of the liver. He once said, "I know I'm drinking myself to a slow death, but then I'm in no hurry." And: "It took me fifteen years to discover that I had no talent for writing, but I couldn't give it up because by that time I was too famous."

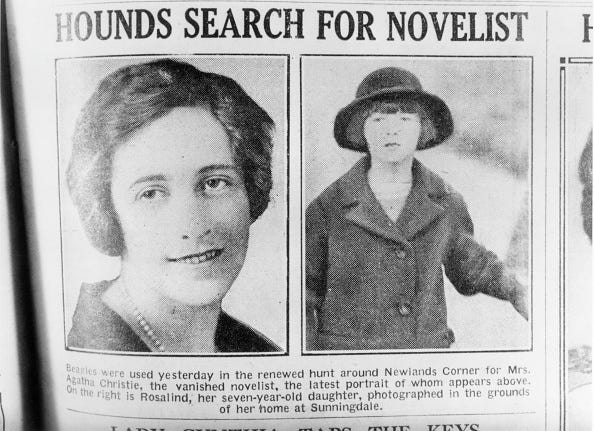

It's the birthday of the mystery novelist and playwright Agatha Christie, born in Devon, England (1890). Her first few books were moderately successful, and then her novel The Murder of Roger Ackroyd came out in 1926. That same year, Christie fled her own home after a fight with her husband, and she went missing for 10 days. There was a nationwide search, and the press covered the disappearance as though it were a mystery novel come to life, inventing scenarios and speculating on the possible murder suspects, until finally Christie turned up in a hotel, suffering from amnesia. During the period of her disappearance, the reprints of her earlier books sold out of stock and two newspapers began serializing her stories. She became a household name and a best-selling author for the rest of her life.

Christie averaged about two novels a year for the rest of her writing career. She jotted down ideas for ingenious murder methods all the time, on scraps of paper and napkins. Her murderers were always members of the upper class, people who dressed well, spoke well, and had great manners, but who just happened to also be killers. She said, "I specialize in murders of quiet, domestic interest."

Be well, do good work, and keep in touch.®

If you are a paid subscriber to The Writer's Almanac with Garrison Keillor, thank you! Your financial support is used to maintain these newsletters, websites, and archive. If you’re not yet a paid subscriber and would like to become one, support can be made through our garrisonkeillor.com store, by check to Prairie Home Productions, P.O. Box 2090, Minneapolis, MN 55402, or by clicking the SUBSCRIBE button. This financial support is not tax deductible.