|

|

The Writer's Almanac from Thursday, November 16, 2017

“A Pink Hotel in California” by Margaret Atwood from Morning in the Burned House. © Houghton Mifflin Company, 1995.

ORIGINAL TEXT AND AUDIO - 2017

It was on this day in 1913 that the first volume of Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time was published. He’d begun work on it in 1909, after taking a nibble of a French pastry cookie dipped in tea. He took it to several publishers, and it was turned down by each one of them. The editor of a prestigious French literary magazine advised that it not be published because of syntactical errors. And one editor said, “My dear fellow, I may be dead from the neck up, but rack my brains as I may I can’t see why a chap should need 30 pages to describe how he turns over in bed before going to sleep.”

So in the end, Proust had to come up with the money himself to self-publish the book, and the first volume appeared in print on this day 104 years ago. He worked on the story for the rest of his life. It was published in seven volumes, and in total it’s about 1.5 million words long.

The novel begins: “For a long time I used to go to bed early. Sometimes, when I had put out my candle, my eyes would close so quickly that I had not even time to say to myself, ‘I’m falling asleep.’ And half and hour later the thought that it was time to go to sleep would awaken me. […] I had gone on thinking, while I was asleep, about what I had just been reading, but these thoughts had taken a rather peculiar turn; it seemed to me that I myself was the immediate subject of my book: a church, a quartet, the rivalry between François I and Charles V. This impression would persist for some moments after I awoke […] Then it would begin to seem unintelligible, as the thoughts of a former existence must be to a reincarnate spirit.”

It’s the birthday of American author Andrea Barrett (1954), born in Boston. She’s best known for novels that explore the relationships between science, history, and humanity, like Ship Fever (1995), which won the National Book Award. Many of her characters are female scientists, often 19th-century biologists.

Barrett became an avid reader early on because the Bookmobile visited her neighborhood once a week. She says: “I would be starved for that visit all week long, and I’d strip the shelves when it arrived. One driver allowed the children to take books from whatever shelves they could reach, and since I’ve always been tall, I could reach the highest shelf, where all the adult books were, at a pretty young age. That worked well for me.”

After college, where she studied zoology and medieval and reformation history, she started writing, holding down jobs like billing clerk, dental assistant, and customer service representative in a corrugated-box factory. The jobs could be tedious, but they also helped her figure out what she wanted to write, and how. She says: “Now it seems to me that what I have, in part, is the mind of a mid-Victorian naturalist. I want to name things; I want to tell stories describing the things I observe.”

After attending a writing conference, her instructor offered to read her manuscript, which later became her first novel, Lucid Stars. His critique was kind, but brutal. She recalled: “The news came deftly padded with reassurance about my probable ability to write, the not-bad story I had written, the things I’d learned writing all those drafts, which would surely help me with what I wrote next, but the kernel of his advice was simple: Throw it out, and move on. Take all you learned writing that and make something new. Afterwards I cried, I fussed, I crashed around — and then I did what he said. What a huge relief to shed those mauled and tortured pages! And how quickly, freed from them, did I begin to write again. That advice made me a writer: I throw out things all the time, still; sometimes things on which I have, as I did with that first novel, spent not only months but years. What’s important, what the attempt taught me about writing, the material I’m exploring, where I want to go next, always survives.”

Barrett’s novels include Lucid Stars (1988), Secret Harmonies (1989), The Middle Kingdom (1991), The Voyage of the Narwhal (1998), and Archangel (2013).

Today is the birthday of columnist, playwright, and director George S[imon] Kaufman (1889), born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He held a variety of sales jobs before he became a writer; then Franklin Pierce Adams featured Kaufman’s work in his column, and on F.P.A.’s recommendation, Kaufman was given a column of his own in 1912, for the Washington Times. He was the drama critic for the New York Times from 1917 to 1930, and found his niche as a playwright during that period. Nearly all of his plays were collaborations. He worked with many of the best writers of the day, including Marc Connelly, Ira Gershwin, Moss Hart, and Edna Ferber, and co-wrote many hits, including Dinner at Eight (1932), You Can’t Take It with You (1935), and The Man Who Came to Dinner (1939). He wrote only one play by himself: 1925’s The Butter and Egg Man, a satire on the theater world. He was an apt satirist, but realized that the genre wasn’t often a big moneymaker; he said, “Satire is what closes on Saturday night.” He wrote musicals for the Marx Brothers, including Animal Crackers (1928) and A Night at the Opera (1935), and was one of the few writers that they approved of and even openly admired.

He loved playing poker and bridge, but was notoriously hard on his bridge partners. He was lean, morose, and a hypochondriac, and he had affairs with some of the most beautiful women on Broadway. His sharp wit also earned him a seat at the Algonquin Round Table, about which he quipped, “Everything I’ve ever said will be credited to Dorothy Parker.” A sample of what he did say: “I like terra firma; the more firma, the less terra.” And, “Epitaph for a dead waiter: God finally caught his eye.” And, “I thought the play was frightful but I saw it under particularly unfortunate circumstances. The curtain was up.”

Be well, do good work, and keep in touch.®

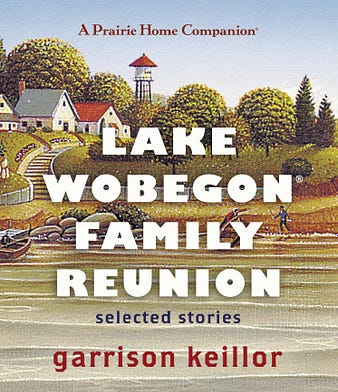

For almost 40 years, Lake Wobegon has served as the fictional hometown of Garrison Keillor and all those who tune in for his weekly radio monologue. Many of us have grown up with "the little town time forgot and decades could not improve" thanks to Keillor's ability to weave a story and tell it live. Assembled using fan input and staff suggestions, this collection of 19 memorable monologues from 40 years of live broadcasts represents some of the very best of Garrison Keillor (so far). Over 5 hours on 4 CDs. CLICK HERE to purchase.

If you are a paid subscriber to The Writer's Almanac with Garrison Keillor, thank you! Your financial support is used to maintain these newsletters, websites, and archive. If you’re not yet a paid subscriber and would like to become one, support can be made through our garrisonkeillor.com store, by check to Prairie Home Productions, P.O. Box 2090, Minneapolis, MN 55402, or by clicking the SUBSCRIBE button. This financial support is not tax deductible.