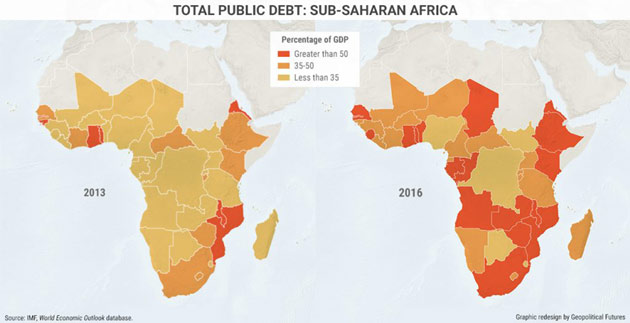

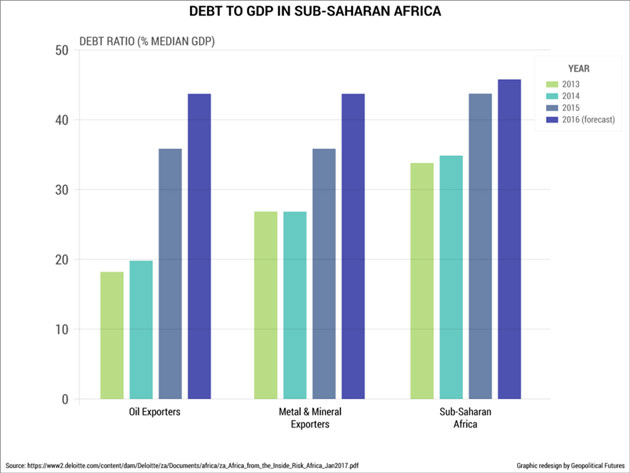

| -- | January 29, 2018 How China Benefits from African Debt By George Friedman and Xander Snyder The level of debt owed by African governments in countries such as Kenya, Uganda, Mozambique, and Tanzania has increased markedly since the 2008 financial crisis. Problematic though sub-Saharan African debt may be, debt levels vary country by country and therefore mitigate the possibility of a continent-wide crisis. Still, widespread default could create opportunities for outside powers that covet the region’s natural resources. How It Happened In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, global interest rates were low, and money was cheap. Investors who sought greater returns turned to riskier investments, including African sovereign debt. Countries across the continent took on debt to fund infrastructure and other development projects. Countries such as Nigeria and Botswana still have debt burdens of under 50 percent of GDP—the level at which debt is generally considered high for developing countries. Other countries such as Mozambique and South Africa have debt burdens of more than 100 percent of GDP. Median public-sector debt in sub-Saharan Africa was 48 percent in 2016.

Source: Geopolitical Futures (Click to enlarge) The current situation resembles the African debt crisis of the 1980s. In the time leading up to the debt crisis, many sub-Saharan African countries similarly took advantage of lower interest rates and took on more debt. When Western central banks raised interest rates to combat inflation, the cost of servicing this debt grew. The fact that many of the loans were denominated in foreign currencies made things worse. When interest rates in the United States went up, the dollar appreciated relative to local currencies in sub-Saharan Africa, making repayment even costlier. Meanwhile, the price of the commodities on which so many of these countries depend fell, decreasing the amount of money they had to pay back their loans. Over the past 10 years, amidst an environment of low global interest rates, African governments have likewise accumulated more debt. As the US and EU economies recovered, central banks have begun to raise interest rates. As much as 70 percent of this debt is denominated in foreign currencies, according to S&P, though the figure is much lower for Nigeria and South Africa, which together constitute a large portion of total sub-Saharan African debt. A decline in global demand for commodities—say, if China were to enter a recession— would once again put pressure on these government revenues, many of which are still dependent on natural resources.

Source: Geopolitical Futures (Click to enlarge) There are two important differences, however, between Africa’s prior debt crisis and its current one. The last one was fueled by a greater share of concessional debt—that is, debt loaned by the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, or other multilateral institutions that generally have better-than-market terms for the borrower. Today, more of sub-Saharan Africa’s debt is private debt (roughly $325 billion of $450 billion total debt, according to S&P). The second and more important difference is that China was not a major power in the 1980s. China’s remarkable industrial growth has required an equally remarkable amount of natural resources for fuel. So, China has been investing more capital in Africa through vehicles like its Export-Import Bank, building infrastructure, and developing trade relations. China has used a form of financing that functions like a bartering system: In return for investment capital and infrastructure development projects, some sub-Saharan African countries grant China resource concessions. (Such was the case with the Sicomines copper project in the Democratic Republic of Congo and in various oil projects in Angola.) The arrangements differ. Sometimes Chinese entities take an ownership stake in the newly constructed infrastructure project. Sometimes loans are secured against resources as a form of collateral. Sometimes debt service is paid in resources instead of money. But just because a loan is backed with an asset—in this case, commodities—doesn’t mean loans can’t turn sour if the borrower struggles to extract or sell enough of its natural resource to service the debt. These terms can also leave the borrowing country with little left over from their commodity production to generate their own revenue. Angola and Congo have both encountered this problem. This kind of financing enables China to invest in places such as Congo, Eritrea, Guinea, and Zimbabwe—countries where the rule of law is relatively weak. And it has a certain logic to it: If a lender needs to be repaid in currency, it needs to ensure that the borrower remains solvent. If a lender is willing to accept payment in the form of a commodity that it can reliably measure, then it can lend to borrowers with riskier credit profiles. Still, these types of deals are fairly rare, the media’s over-reporting on them notwithstanding. Estimates vary wildly—data on Chinese financing is scant and must be collected indirectly—but a report written in 2016 by Deborah Brautigam, a professor of international political economy at John Hopkins, estimated that Chinese banks, contractors, and the government lent approximately $86 billion to Africa between 2000 and 2014. About $29 billion of that was loans backed by natural resources. That’s not such a large amount, considering it covers a 14-year period and nearly 50 countries. In terms of foreign direct investment, China still spends less in Africa than the United States, the United Kingdom, and France, whose FDI stocks in Africa were $64 billion, $58 billion, and $54 billion, respectively. (However, Chinese investment accelerated more quickly than the others between 2010 and 2015.) | “I was skeptical when you claimed it was the ‘best conference,’ but after last year, I couldn’t praise the SIC enough.” Interested in attending 2018’s premier investment gathering? Reserve your seat now! |

Opportunity in Crisis? Africa is a minor player in geopolitics. Unfortunate as it may sound, its relevance stems from how stronger countries interact with it and manipulate it. So while its current indebtedness may not shape the course of international affairs directly, it may, in fact, benefit China. Defaulting on their debt would cause foreign investment to dry up. China’s willingness to accept repayment in commodities would leave it as one of the few remaining options for countries struggling to build infrastructure. Beijing could, therefore, drive as hard a bargain as it wanted. China will continue to mine Africa for its resource needs. The only thing that will constrain its behavior in that regard is its own capital needs. It will, in other words, have to determine how much to spend as its own economic problems continue to mount. Were this to transpire, it’s possible that China’s rivals, noticing how much Beijing benefits from its relationship with Africa, would begin to follow suit, generating a renewed Great Game competition on the continent. This could take the form of other resource-dependent countries that are opposed to China, such as Japan, seeking similar quasi-barter deals on the continent in exchange for secured access to commodities. But what is possible is not particularly likely. A debt crisis would have social implications that would make doing business extremely difficult, limiting the upside to China and decreasing the likelihood of other powers opting to compete with it. Even if it did, the arena would be peripheral to great powers’ core interests. Unlike the colonial economies of the 17th–19th centuries that drove European competition in Africa among other places, the scale of modern-day economies and their supply chains rely on a global market rather than sequestered mercantilist ones. China’s presence and influence in Africa is real, but in terms of global geopolitical consequence, it is likely to remain limited.

George Friedman

Editor, This Week in Geopolitics

| Prepare Yourself for Tomorrow with George Friedman’s This Week in Geopolitics

This riveting weekly newsletter by global-intelligence guru George Friedman gives you an in-depth view of the hidden forces that drive world events and markets. You’ll learn that economic trends, social upheaval, stock market cycles, and more... are all connected to powerful geopolitical currents that most of us aren’t even aware of. Get This Week in Geopolitics free in your inbox every Monday. |

Share Your Thoughts on This Article

Not a subscriber?

Click here to receive free weekly emails from This Week in Geopolitics.

Use of this content, the Mauldin Economics website, and related sites and applications is provided under the Mauldin Economics Terms & Conditions of Use. Unauthorized Disclosure Prohibited The information provided in this publication is private, privileged, and confidential information, licensed for your sole individual use as a subscriber. Mauldin Economics reserves all rights to the content of this publication and related materials. Forwarding, copying, disseminating, or distributing this report in whole or in part, including substantial quotation of any portion the publication or any release of specific investment recommendations, is strictly prohibited.

Participation in such activity is grounds for immediate termination of all subscriptions of registered subscribers deemed to be involved at Mauldin Economics’ sole discretion, may violate the copyright laws of the United States, and may subject the violator to legal prosecution. Mauldin Economics reserves the right to monitor the use of this publication without disclosure by any electronic means it deems necessary and may change those means without notice at any time. If you have received this publication and are not the intended subscriber, please contact service@mauldineconomics.com. Disclaimers The Mauldin Economics website, Yield Shark, Thoughts from the Frontline, Patrick Cox’s Tech Digest, Outside the Box, Over My Shoulder, World Money Analyst, Street Freak, ETF 20/20, Just One Trade, Transformational Technology Alert, Rational Bear, The 10th Man, Connecting the Dots, This Week in Geopolitics, Stray Reflections, and Conversations are published by Mauldin Economics, LLC. Information contained in such publications is obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but its accuracy cannot be guaranteed. The information contained in such publications is not intended to constitute individual investment advice and is not designed to meet your personal financial situation. The opinions expressed in such publications are those of the publisher and are subject to change without notice. The information in such publications may become outdated and there is no obligation to update any such information. You are advised to discuss with your financial advisers your investment options and whether any investment is suitable for your specific needs prior to making any investments.

John Mauldin, Mauldin Economics, LLC and other entities in which he has an interest, employees, officers, family, and associates may from time to time have positions in the securities or commodities covered in these publications or web site. Corporate policies are in effect that attempt to avoid potential conflicts of interest and resolve conflicts of interest that do arise in a timely fashion.

Mauldin Economics, LLC reserves the right to cancel any subscription at any time, and if it does so it will promptly refund to the subscriber the amount of the subscription payment previously received relating to the remaining subscription period. Cancellation of a subscription may result from any unauthorized use or reproduction or rebroadcast of any Mauldin Economics publication or website, any infringement or misappropriation of Mauldin Economics, LLC’s proprietary rights, or any other reason determined in the sole discretion of Mauldin Economics, LLC. Affiliate Notice Mauldin Economics has affiliate agreements in place that may include fee sharing. If you have a website or newsletter and would like to be considered for inclusion in the Mauldin Economics affiliate program, please go to http://affiliates.ggcpublishing.com/. Likewise, from time to time Mauldin Economics may engage in affiliate programs offered by other companies, though corporate policy firmly dictates that such agreements will have no influence on any product or service recommendations, nor alter the pricing that would otherwise be available in absence of such an agreement. As always, it is important that you do your own due diligence before transacting any business with any firm, for any product or service. © Copyright 2018 Mauldin Economics | -- |