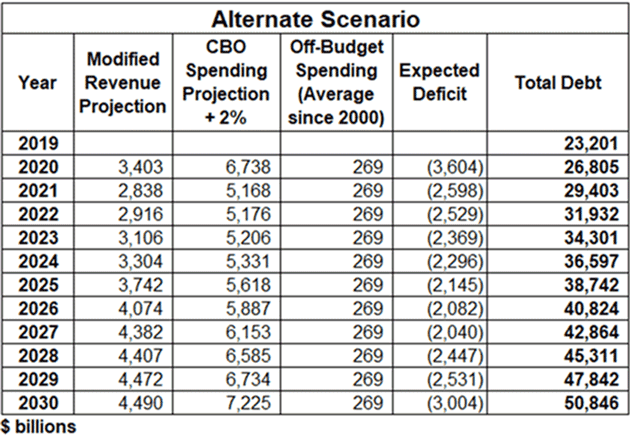

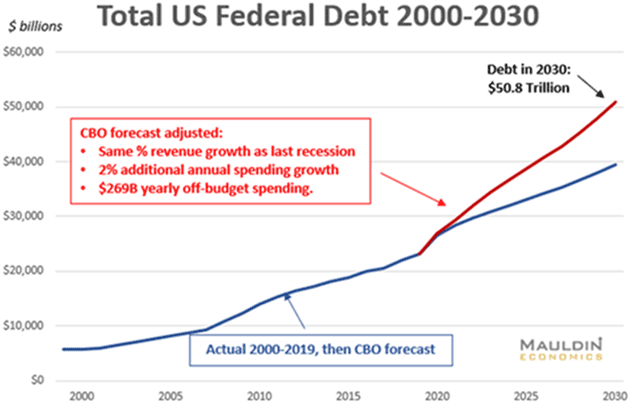

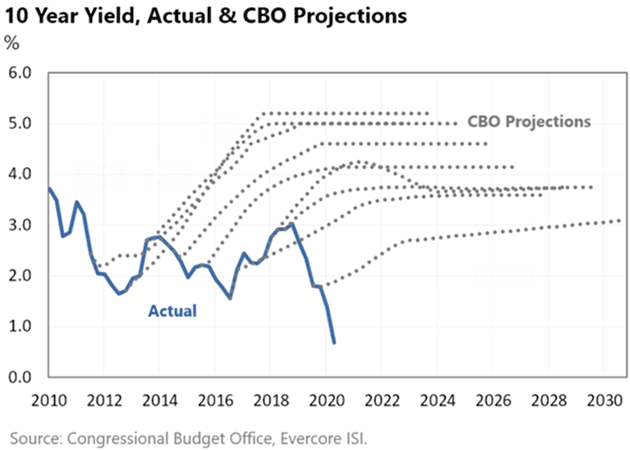

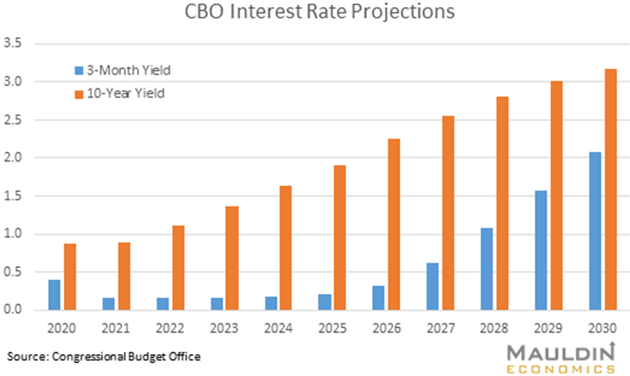

Debt Bugs and Windshields By John Mauldin | Oct 03, 2020     "There is no means of avoiding the final collapse of a boom brought about by credit expansion." —Ludwig von Mises Economic recovery is coming, we are told, because the economy has found a new equilibrium. We are supposedly adapting to the new-normal pandemic world, with monetary and (some) fiscal stimulus filling any gaps. Except that’s not what the data says. Last week I laid out the case that US government debt would be $50 trillion by 2030. That was using straight-line CBO projections but using the 2008 recovery pattern for government revenue plus adding in off-budget debt which averages about $269 billion a year. USdebtclock.org is now projecting off-budget deficit to rise by over $1 trillion this year. Most of my feedback didn’t dispute the amounts; the disagreement was whether so much debt is a serious problem. Today, rather than just stating the recovery will be slower, I will try to make the case for a much slower recovery thus much higher debt by 2030. Note first, I’m not saying there will be no recovery. I am simply postulating it will look like the slow recovery from the Great Recession, unless the government makes it worse, which is a nontrivial possibility. Let’s quickly review the two charts that were at the end of the last letter.   To be fair, there are reasons to think a $50 trillion debt load is “manageable.” It depends on what you consider “manageable” is. Maybe survivable is a better word. But it will clearly slow or kill GDP growth. Think Japan and Europe. “Net Interest” is a significant and growing slice of federal spending. When your debt balance is measured in trillions, even tiny interest rate differences matter. Uncle Sam gets a good deal because investors believe their Treasury purchases carry no credit risk. The main concern is inflation, enough of which could drive rates higher and raise the government’s borrowing costs. Even the CBO’s optimistic projections show tax revenue barely covering “mandatory” entitlement spending and net interest in the next few years. Congress will have to either find more revenue or make big cuts to “discretionary” spending—which includes most of what we think the government does: defense, diplomacy, regulation, etc. That could get ugly. However, the CBO projections are likely wrong. Their borrowing cost estimates depend on interest rate assumptions that have been unreliable, to say the least. The dotted lines below show CBO’s annual projections vs. the actual yield. You can see reality has been almost always lower than it thought.  Of course, when you’re planning a budget you want to err on the side of caution. It helps avoid nasty surprises. The government’s interest costs have been mostly lower than expected because interest rates were lower than planned. The deficit might have been even higher otherwise. Here’s a closer look at CBO’s best guess.  CBO expects a steady rise in the 10-year bond yield after 2021. Note, the government’s borrowing costs depend heavily on the maturity at which debt is issued and then rolled over (since no one expects the government to actually pay it down). With long-term yields now at historic lows, it seems to me it should back up the truck and sell as much 10-year paper as the market will buy. That’s what any CFO would do in this environment: Borrow as much as you can for as long as you can. Let me make it an even more aggressive assumption. If the government really thinks the 10-year is going to 3% in 2030 it should be selling every 30-year bond it can at 1.45% or 20-year bonds at 1.23%. Perhaps see if the market would take 50-year bonds as some countries have. While I don’t think we will do it in the next year, it would not surprise me that in the future we will sell something that looks like the old British consols, which were interest-only perpetual bonds. (Historical trivia: The US sold consols in 1870 at 4%. They have all been redeemed.)

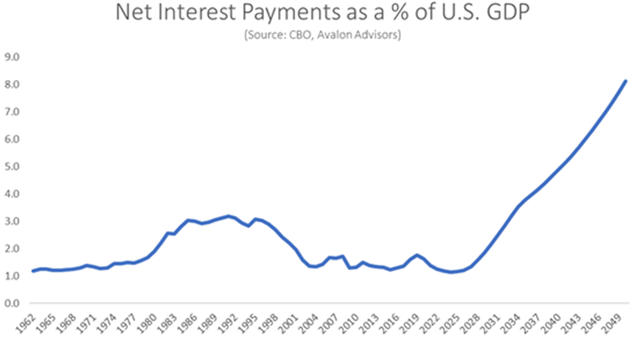

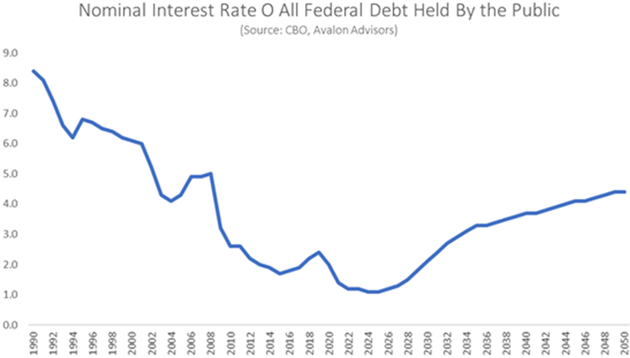

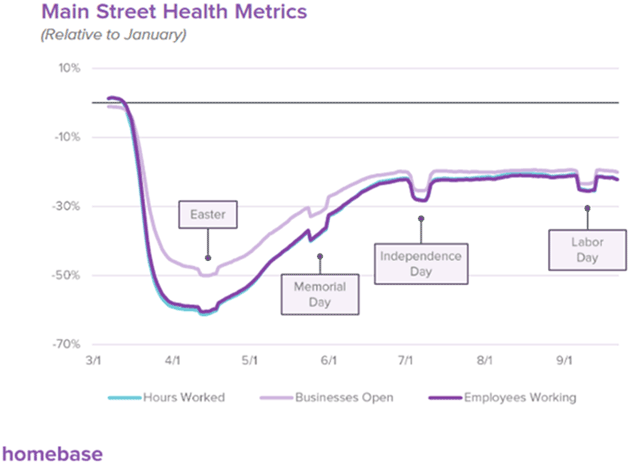

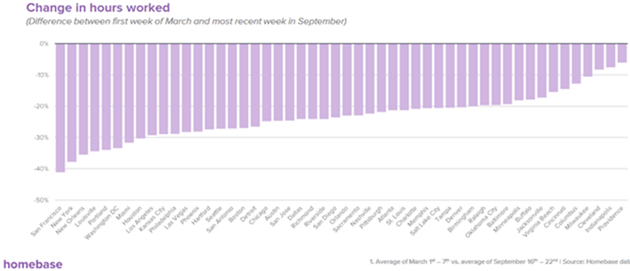

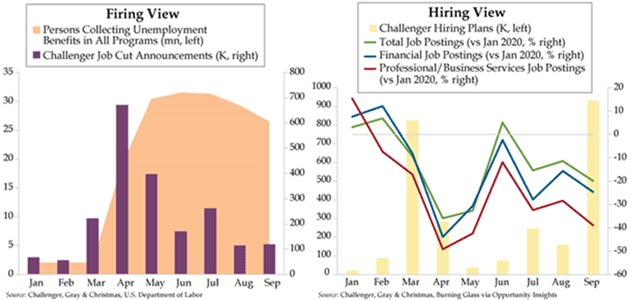

Source: Wikimedia Commons The Federal Reserve is another factor in the government’s favor. It uses excess bank reserves and its own balance sheet to buy Treasury debt, then gives the interest it receives right back to the Treasury. So that part of the federal debt is effectively at 0% interest. I believe the Federal Reserve will engage in Yield Curve Control if long-term interest rates move too high. That is, of course, financial repression and a monster body blow to the retiring Boomer generation. All this leads many smart people whom I greatly respect, like Samuel Rines, to conclude the federal debt isn’t a problem for now. Looking at the numbers as a percent of GDP, and considering the CBO long-term forecasts out to 2050, Sam writes this: In its latest round of projections, by far the most intriguing portion of the analysis related to the dynamics around the US federal debt load. The US debt load has increased dramatically due to the response to COVID, but the ability to service the US debt load is actually improving. Measured by interest payments on the debt relative to GDP, the US's fiscal situation is set to improve for the better part of the next decade. In fact, the figure is set to hit 1.1% in 2024. That is the lowest level of interest payments to GDP since at least the early 1960s.  But that is where the projections become a bit less sanguine. Instead of going lower and remaining lower, interest payments then begin to rise, and continue to do so until the end of the projections in 2050. At 8.1%, the CBO is projecting interest payments on debt will grow to be more burdensome than Social Security as a percent of GDP. That is quite the assertion. But that is not the entirety of the story. There are a few assumptions made by the CBO that are rather suspect.  The obvious reason for increasing interest payments is a projection of rising borrowing costs. And that is where the CBO's analysis begins to show a few potential holes. Sam thinks the federal debt will become a bigger problem when the economy improves and interest rates rise. I would argue much of that rise is already built into CBO’s high-side rate projections. But there’s another wrinkle. Based on CBO’s past record, their forecast for 3% ten-year yields in 2029 looks dubious to me. It has been well below that level for most of the last decade. What would make rates rise that much? The only answer is some combination of a stronger economy and higher inflation. The Fed recently revised its policy framework to “let” inflation run higher for longer. That’s the same Fed which has targeted 2% inflation for years now without success, at least on its own preferred benchmark. (The Fed has certainly generated asset price inflation.) There is good reason for this. The kind of broad inflation the Fed says it wants can’t happen unless the economy outstrips productive capacity for key goods and services. Without that, general price levels simply can’t rise. Certain prices (rent and healthcare, for example) can rise enough to cause significant discomfort, but price weakness elsewhere keeps it from affecting the benchmarks too much. Lacy Hunt and others have long argued, and been proven correct so far, that rising debt actively suppresses economic growth. Debt service prevents everyone (government, businesses, and households) from investing enough capital to generate long-term growth. This is why each new dollar of debt is producing less additional GDP. We are borrowing to fund consumption instead of production. It gets worse. The Fed thinks it can encourage growth by keeping interest rates low. But in fact, its “forward guidance” (pledging low rates long into the future) gives no one any reason to act now. With no fear of rising rates as motivation, you might as well wait. Peter Boockvar has been saying this for a long time and he’s absolutely right. Add our aging population and other demographic challenges, and there’s no reason to expect substantially higher GDP growth by 2030. Some sectors will prosper, of course, as technology has in recent years. But others will suffer, leaving the macro growth outlook no better than it has been. Even the CBO’s rosy scenarios show the economy spending 2021 and 2022 simply digging out of the 2020 hole, then a return to the same sluggish growth as almost every year since 2005. But if that’s what happens, we should be grateful. Let’s look at why it will likely be worse. Economists who expected a quick recovery from this recession have been revising their forecasts. Mounting evidence suggests the May/June bounce was just that, a bounce, and not a return to prior trends. I’ve been following Homebase, a payroll/HR data provider for small businesses, whose data gives us high-frequency and nearly real-time information. This is from their September report:  You can see a sharp decline during the initial lockdown period and then improvement as many states reopened. But since then, activity has flatlined except for some holiday dips. There’s a great deal of local variation.  Not surprisingly, work hours dropped the most in places with the deepest and longest-lasting lockdowns, like New York and California. But even the best metro areas show a 5–10% drop, with many down 20% or more. This points to a much longer recession than bulls think. The official unemployment rate is now 7.9% but is certainly understated. Even 10% is likely optimistic. There are 25 million+ people who are still getting some type of unemployment claims and job postings are down. From Friday’s Daily Feather (courtesy of my friend Danielle DiMartino Booth):

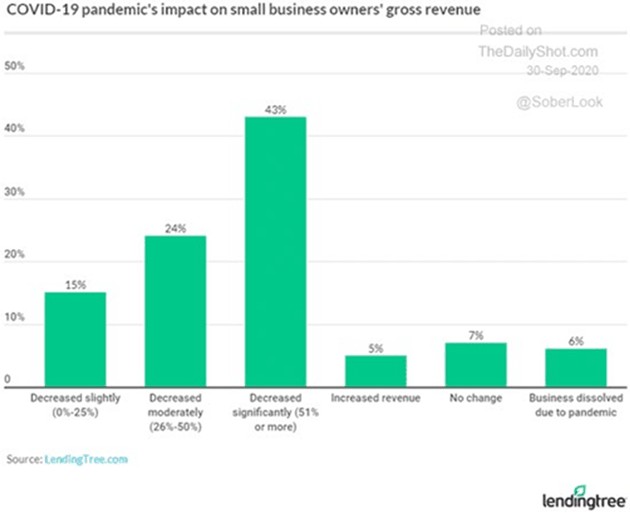

Source: Quill Intelligence Worse, even the small businesses that are hanging on are in major distress. A Lending Tree survey shows 43% have seen revenue drop by half or more, and 6% have already dissolved.

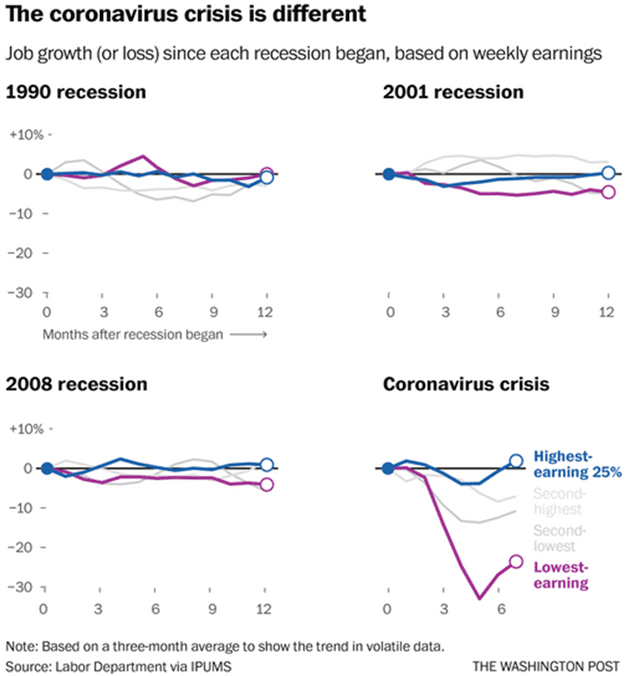

Source: The DailyShot We have never seen anything like this in history, with a possible exception (percentage wise) during the Great Depression. This is not the material from which V-shaped recoveries are created. Worse, this recession has been inordinately destructive for the bottom 25% of income earners.

Source: The Washington Post That is why it is absolutely critical that Congress pass some type of Phase IV relief bill. Consumer spending has held up due to the initial pandemic relief. Now many live on savings, if they have any. We are getting ready to fall off an economic cliff without more relief. Obviously, much depends on how much the coronavirus case load increases/decreases over the winter, and whether a working vaccine can be approved and distributed. The logistics will take enormous coordination. It is doable but not guaranteed. What if 2021, instead of being the start of recovery, takes the economy even deeper into recession? Mind you, I’m not predicting that, but it is a significant possibility that would need far more fiscal support than even the $2T+ Phase IV bill Democrats passed in Congress yesterday. And because lower growth will mean lower tax revenue, we will add trillions more to the debt. We can easily see another $3 trillion worth of debt in 2021. Easily. Even if we see an effective vaccine widely distributed by spring to mid-2021, I think continued stagnation is the best case for GDP in the coming decade. If we have another recession the national debt will rise to $60 trillion by 2030. That’s just the nature of recessions. I think we will probably see tax increases and maybe a major restructuring of the tax code, especially when we get to The Great Reset. We will be open to new innovation at that point, which may prove helpful in the long run. I think some kind of consumption tax (like the VAT used in almost every other country in the world) paired with an income tax only on high earners would be far less economically distorting than the current mishmash. But the transition will be disruptive at best, and our political heroes could easily turn it into a fiasco. But a $60 trillion debt could force us to take actions that we would otherwise not consider. I’m going to quote at length from my friend David Rosenberg in his Wednesday letter. I believe he is absolutely spot on and he says it better than I would. We’ll jump in where he cites a Chicago Fed survey of distressed business sectors: You tally up these sectors and before the crisis, they supported 32 million jobs, or about a third of the private sector workforce, and it looks to me as though half of them are not going back to their old jobs. And I’m not sure many people understand that amusement parks, airlines, hoteliers and restaurants cannot stay in business at 50% capacity (or even 75% in the case of restaurants). …As it stands, the US Chamber of Commerce said that 25% of small businesses have already shut down. Another survey by Ipsos concluded that two-thirds are still nervous about leaving their homes; 59% say they intend to remain locked down on their own until signs emerge that the virus is “fully contained.” A YouGov/CBS poll concludes that 85% of American households say they wouldn’t get on an airplane even if they could. That’s why the industry needs a bailout! A Washington Post/University of Maryland poll shows that only 56% of consumers across the nation intend to shop at the supermarket, which I suppose is a continuous bullish data point for delivery services but that’s about it. Just 33% say they are comfortable entering a retail store. And a mere 22% say they are willing to dine in a sit-in restaurant. All these polls say basically the same thing—it will not be “business as usual,” as the bulls will try and convince you, and the best we can hope for is a partial recovery. I mean, at best. What we had on our hands was a vertical down economic decline with job losses an order of magnitude higher than anything we have witnessed since the Great Depression. So, even as the stock market is telling you it has it all figured out, I can assure you that what we face at this very moment is a very uncertain economic future. And unfortunately, most of the longer-term risks are to the downside. We are in a depression—not a recession, but a depression. And I think the dynamics of a depression are different than they are in a recession because depressions invoke a secular change in behavior. Classic business cycle recessions are forgotten about within a year after they end—the scars from this one will take years to heal. Disney said this week it is laying off 28,000 workers. American Airlines and United Airlines plan to cut 31,000 workers. Today’s disappointing unemployment report shows that we have a long way to go. Even though the unemployment rate went down to 7.9%, that was largely due to a drop of almost 700,000 in the labor force. We have regained just over half the jobs lost between February and April. The pace of gains, both total and private, slowed for the third consecutive month and looks to get slower. There will be a recovery. Those hundreds of thousands of entrepreneurs who have closed their businesses? They’ll open new ones. But not in six months. Where will they get capital? It’s one thing to bail out airlines with multiple billions of dollars. What about the local bakery with 15 employees? Where do they get the capital to reopen when the time is right? And you can repeat that story a million (or more) times. Which brings us back to my conclusion: That which can’t go on, won’t. We can’t keep piling on debt at this rate forever, and we can’t repay what we have. I used to say Japan was a bug in search of a windshield. Now it’s not just Japan. As I file this letter, news just broke about President Trump and First Lady Melania Trump testing positive for COVID-19. Let me express my sincere wishes they (and all others afflicted by this awful virus) make a speedy recovery. I have no idea what this means for the election and I think speculation would be inappropriate. But as Rosie mentioned above, the reason for his depression call and my deep recession and slow recovery projection is the fact that this COVID pandemic is significantly changing behavior. I can’t imagine this making those behavioral changes any better. On a lighter note, I turn 71 on Sunday. When I was in my 20s, 70 sounded and even looked really old. Not so much anymore. In more idyllic times, and especially in my youth, my one birthday cake request was my mother’s banana nut cake. I mentioned it a few weeks ago and a large number of readers asked for the recipe. We have just kept putting it off but finally, here it is: Ingredients: - ½ cup butter

- ½ cup sugar

- two eggs

- three medium bananas

- ½ cup chopped pecans

- 2 cups flour

- 1 teaspoon soda

- pinch of salt

- 4 tablespoons of buttermilk

- 1 teaspoon of vanilla

Cream the butter, sugar and eggs, then bananas, buttermilk and vanilla. Mix until smooth. Sift flour, salt and soda, then add to other ingredients in a mixer and beat well. This makes two layers (9” square pans). Grease and flour the pans. Cook at 325° until brown. Use a toothpick to make sure it is cooked throughout. Now, changes I’ve made: We were poor when we grew up. Seriously. Mother cut back on every recipe she ever made. (She used oatmeal in her meatloaf and hamburgers because hamburger meat was expensive at three pounds for a dollar.) Many times she used oleo in the cake rather than butter. I use three eggs and double the chopped pecans. I am more generous with the butter. Remember bananas are bigger today than they were 60 years ago. I like to use brown sugar but when Tiffani makes the recipe she uses white sugar which is more like what mother’s cake tasted like. Of course, banana cake needs icing. That is simply ¼ pound butter (typically a stick), two medium bananas, one box of powdered sugar and a cup of chopped pecans. I might add a little extra butter and pecans. Note: You have to let the bread cool before you can put the icing on. I typically put the icing in the refrigerator for an hour. And don’t forget to put the icing between the layers. Shane is making me a small banana cake for my birthday Sunday. Maybe a few friends will be there. I will have a Zoom birthday call with my kids. In any event, you have a great week. Your 71 but making 15-year business plans analyst,   | John Mauldin

Co-Founder, Mauldin Economics |

P.S. Want even more great analysis from my worldwide network? With Over My Shoulder you'll see some of the exclusive economic research that goes into my letters. Click here to learn more.    | | Share Your Thoughts on This Article | | |

|