EUROPE HAS TRAIN WRECKS, TOO By John Mauldin | Jun 22, 2018 Italian dictator Benito Mussolini at least made the trains run on time, according to legend. But other sources say the nation’s railway system remained horrible under his rule (see here, here, and here). | | | | | - | Until June 30... And then it’s gone If you’ve ever considered joining Jared Dillian’s premium publications, now is the time to act. Until June 30, you can get a special bundle with Street Freak, The Daily Dirtnap, and ETF 20/20 at the lowest price you’ll ever see... GET IT NOW! | - | | | | |

|

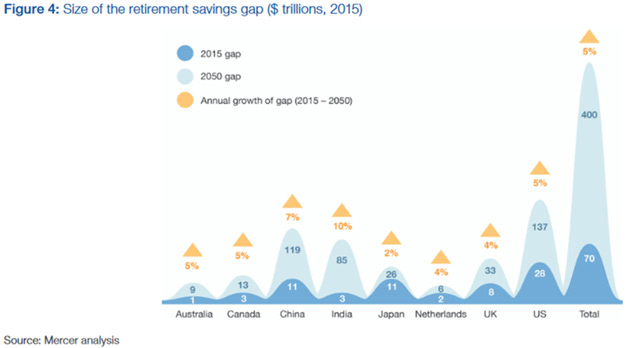

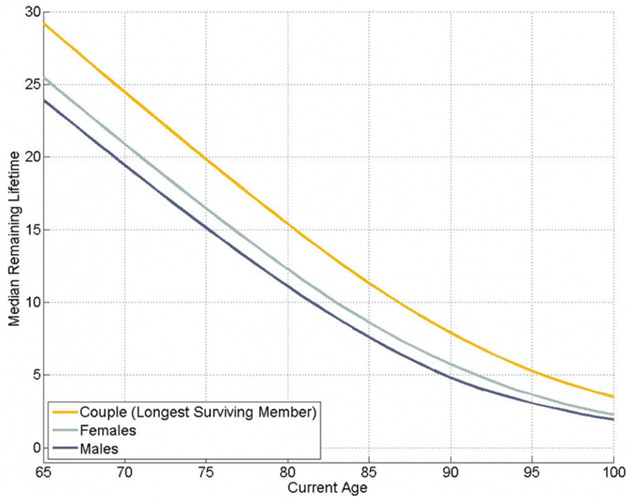

The same may be true of modern Europe’s (and Canada and Australia and…) vaunted social welfare programs. Certainly, they have helped many people, but they haven’t eliminated poverty, nor let everyone retire in comfort. Could they simply have shifted spending forward, leaving future generations with the bill? Today, we’ll explore that question as part of my continuing Train Wreck series. Last week, I looked at US public pension funds, many of which are woefully underfunded and will likely never pay workers the promised benefits—at least without dumping a huge and unwelcome bill on taxpayers. And taxpayers are generally voters, so it’s doubtful they will pay that bill. (Even the Swiss, as we will see below, voted against a mild reform to pay for their pension system.) Non-US readers might have felt a little satisfaction at that. There go those crazy Americans again, spending wildly beyond their means. You are partly correct; we aren’t exactly the thriftiest people on Earth. However, your country may be more like the US than you think. This letter is chapter 7 in my Train Wreck series. If you’re just joining us, here are links to prior installments. Last year, a World Economic Forum study looked at six developed countries (the US, UK, Netherlands, Japan, Australia, and Canada) and two emerging markets (China and India) and found a $400 trillion retirement savings shortfall by 2050. That’s how much more is needed to ensure everyone of retirement age will receive 70% of their working income, including government, employer, and personal savings—but mostly government. This staggering number—more than the entire planet’s annual GDP—doesn’t even include most of Europe. Yet unless those countries somehow find the cash, they will break the promises they’ve made to today’s workers.  $400 trillion sounds like a lot of money. It is. But the eight countries in that total represent around 60% of global GDP (my back-of-the-napkin calculation), so you could say that we should add another $250 trillion to get the total global retirement gap. Your mileage may vary by country and demographics. And for many countries, like the US, that doesn’t include healthcare and other obligations. The final letter of this series will start adding everything up. I actually haven’t done that calculation yet, but we may scare one quadrillion dollars, with a “Q.” That’s with a global economy that is less than $80 trillion today. Remember what I’ve said in this series so far: Promises like these are debt, whether they show as such on the balance sheet or not. Breaking them is equivalent to debt default. The creditors (workers) will certainly perceive it that way, at least. As I’ve also noted, increasing life expectancies are driving this problem. Reaching age 100 is already less remarkable than it used to be. That trend will continue. The good news is we will also be in better health at those advanced ages than people are now. Could 80 be the new 50? We’d better hope so, because the math is bleak if people stop working at age 65–70, which is precisely what the Wall Street Journal wrote this week on their front page. And we see it in the lack of workers available out in the real world. That said, I think we will see a great deal of national variation in these trends. Some countries have robust government-provided retirement plans, others depend more on employer and individual contributions. In the big picture, though, the money simply isn’t there. Nor will it magically appear just when it’s needed. WEF reached the same conclusion I did long ago: This idea of spending decades in leisure before your final decline is unfeasible and is quickly reaching its limits. Most of us will work well past 65, whether we want to or not. What about the millions presently in retirement, or nearly so? That’s a big problem, particularly for the US public-sector workers I wrote about last week. We should also note that we’re all public-sector workers in a way, since we must pay into Social Security and can only hope Washington eventually gives us something back. And this is going to get worse as the new anti-aging technologies spread. Some are here now. Here is the current life expectancy chart, via Wade Pfau writing at Forbes.

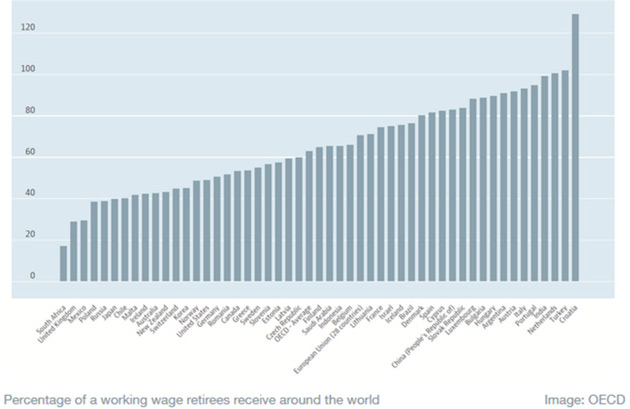

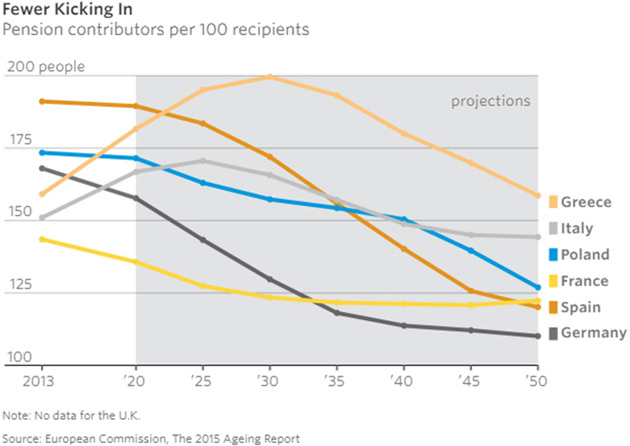

Source: Wade Pfau When the anti-aging tech kicks in, we will need to shift those curves to the right ten years (at least!!!!). And then I think age reversal will show up by the early 2030s and be ubiquitous by the 2040s. That’s great news for those who want to live longer, younger, and healthier, but it will force radical changes in our retirement and work. Meanwhile, automation will be killing millions of jobs. (By the way, our own Patrick Cox is on top of all this and we’re planning some Mauldin Economics white papers this fall that will outline the possibilities for extending your health span.) Now, let’s look at a few individual countries. We’ll start with our closest European ally, the United Kingdom. The WEF study shows the UK with a $4 trillion retirement savings shortfall as of 2015, projected to rise 4% a year and reach $33 trillion by 2050. In a country whose total GDP is around $2.6 trillion, the shortfall is already bigger than the entire economy and, with even modest inflation, will get worse. Further, this was calculated before the UK decided to leave the European Union. That major economic realignment could certainly change the outlook. Whether for better or worse, I don’t know yet. The answer depends on which of my friends I ask and what side of the Remain or Leave fence they are on. A 2015 OECD study said developed-country workers could on average expect governmental programs to replace 63% of their working-age income. Not so bad. But in the UK, that figure is only 38%, the lowest of all OECD countries. This means UK workers must either save more personally or severely cut spending when they retire. UK employer-based savings plans aren’t on especially sound footing, either. According to the government’s Pension Protection Fund, some 72.2% of the country’s private-sector defined benefit plans are in deficit, and the shortfalls total £257.9 billion. Government liabilities for pensions went from well-funded in 2007 to a £384 billion (~$500 billion) shortfall ten years later and no doubt grew further since. Again, that is a rather large amount for a less than $3 trillion economy. To this point, UK retirees have had a kind of safety valve: the ability to retire in EU countries with lower living costs. That option may disappear after Brexit. A report last year from the International Longevity Centre suggested younger workers in the UK need to save 18% of their annual earnings in order to have an “adequate” retirement income, which it defines as less than today’s retirees enjoy. That’s just fantasy. No such thing will happen, so the UK is heading toward a retirement implosion that could be at least as chaotic as in the US. Americans often have a romanticized stereotype of Switzerland. It is certainly one of my favorite countries. We think it’s the land of fiscal discipline and rugged independence. To some degree it is, but Switzerland has its share of problems, too. The national pension plan has been running deficits as the population grows older. Last summer, Swiss voters rejected a pension reform plan that would have strengthened the system by raising the women’s retirement age from 64 to 65 and raising taxes and required worker contributions. These mild changes still went down in flames as 52.7% of voters said no. Voters around the globe usually want to have their cake and eat it, too. We demand generous benefits but don’t like the price. The Swiss, despite their reputation, appear not so different. Consider this from the Financial Times. Alain Berset, interior minister, said the No vote was “not easy to interpret” but was “not so far from a majority” and work would begin soon on revised reform proposals. Bern had sought to spread the burden of changes to the pension system, said Daniel Kalt, chief economist for UBS in Switzerland. “But it’s difficult to find a compromise to which everyone can say Yes.” The pressure for reform was “not yet high enough,” he argued. “Awareness that something has to be done will now increase.” That describes most of the world’s attitude. Both politicians and voters ignore the long-term problems they know are coming and think no further ahead than the next election. That quote, “Awareness that something has to be done will now increase,” may be literally true, but there’s a big gap between awareness and motivation—in Switzerland and everywhere else. Now, the irony is that even with their problems, the UK and Switzerland are better off than much of Europe. They actually have mandatory pre-funding with private management and modest public safety nets, along with Denmark, the Netherlands, Sweden, Poland, and Hungary. (Sidebar: Low or negative rates in all those countries make it almost impossible for their private pension funds to come anywhere close to meeting their mandates without large annual contributions for those companies or insurance sponsors, which reduce earnings. And many are required by law to invest in government bonds with either negligible or negative returns.) Conversely, France, Belgium, Germany, Austria, and Spain are all Pay-As-You-Go countries (PAYG), with nothing saved in the public coffers for future pension obligations. Pension benefits come out of the general budget each year. The crisis is quite predictable because the number of retirees is growing while the number of workers paying into the general budget falls. Further, falling fertility in these countries makes the demographic realities even more difficult. Spain bounced back from recent crises more vigorously than some of its Mediterranean peers like Greece. That’s also true of its national pension plan, which actually had a surplus until recently. Unfortunately, the government “borrowed” some of that surplus for other purposes and it will soon become a sizable deficit. The irony here is that, just like the US, Spain’s program is called Social Security, but like our version, is neither social nor secure. Both governments have raided supposedly sacrosanct retirement schemes, and both use those savings for whatever the political winds favor. Spain has 1.1 million more pensioners than just 10 years ago, and as the Baby Boom generation retires, it will have even more. Unemployment as high as 25% among younger workers doesn’t help, either. Of the two, the US is in “better” shape, mainly because we control our own currency and can debase it as necessary to keep the government afloat. US Social Security checks will always clear even if they don’t buy as much. Spain doesn’t have that advantage if it stays tied to the euro currency. That’s one reason the eurozone could eventually spin apart. In at least some of those pay-as-you-go countries, public pension plans allow early retirement at age 60 or below. The contribution rate by workers is generally less than 25%. Worse, some governments pay retirees more than they made while actually working. This OECD chart shows pension benefits as a percentage of working wages. It is more than 100% in Croatia, Turkey, and the Netherlands, and above 90% in Italy and Portugal.

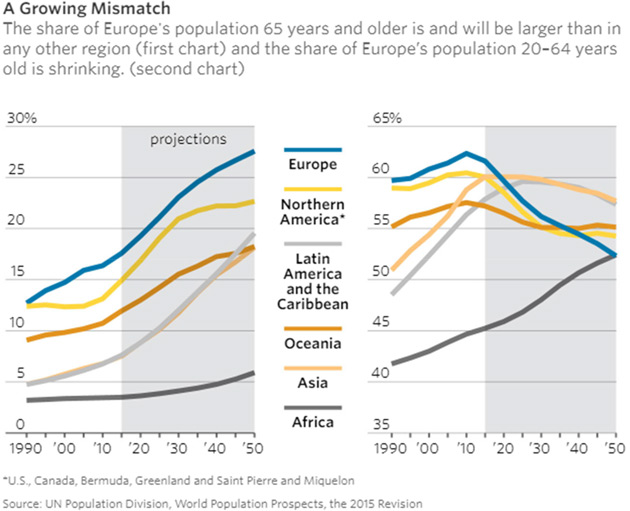

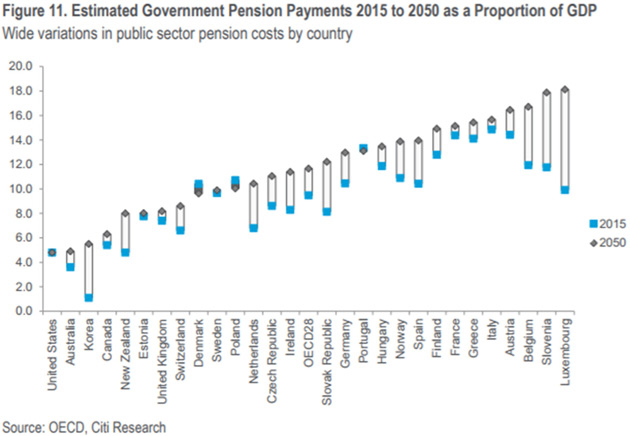

Source: OECD Pensions at a Glance 2017 I am sorry, but there is simply no way this can continue. These governments have legislated rainbows and unicorns. They will not deliver such benefits, unless it is because wages and benefit payments crash to unimaginably low levels. A rather bleak Wall Street Journal special report focused on the formidable demographic challenges. Europe’s population of pensioners, already the largest in the world, continues to grow. Looking at Europeans 65 or older who aren’t working, there are 42 for every 100 workers. This will rise to 65 per 100 by 2060, the European Union’s data agency says. By comparison, the US has 24 non-working people 65 or over per 100 workers, says the Bureau of Labor Statistics, which doesn’t have a projection for 2060. Unlike most European financial stories, this isn’t a north-south problem. Austria and Slovenia face difficult demographic challenges right along with Greece. This WSJ chart compares the share of Europe’s population 65 years and older to other regions, and then the share of population of workers between 20 and 64. These are ugly statistics.  Across Europe, the birthrate has fallen 40% since the 1960s to around 1.5 children per woman, according to the United Nations. In that time, average life expectancies have risen from around 69 to roughly 80 years. In Poland, birthrates are even lower, and there the demographic disconnect is compounded by emigration. Taking advantage of the EU’s freedom of movement, many working-age Polish youth leave for other countries in search of higher pay. A paper published by the Polish central bank forecasts that by 2030, a quarter of Polish women and a fifth of Polish men will be 70 or older.  Everything I read about the pay-as-you-go countries in Europe suggests that they are in a far worse position than the United States. Plus, their economies are stagnant, and the tax burden is already near 50% of GDP. Moreover, many private pensions are in seriously deep kimchee, too. Low and negative interest rates have devastated the ability to grow assets. Combined with public pension liabilities, the total cost of meeting the income and healthcare needs of retirees as a percentage of GDP is going to dramatically increase across Europe. Think about that for a moment. I am not talking about as a percentage of tax revenues. I am talking about as a percentage of GDP that in Belgium will be 18% in about 30 years. Which would be 40–50% of total tax revenues. That doesn’t leave much for other budgetary items. Greece, Italy, Spain? Not far behind…

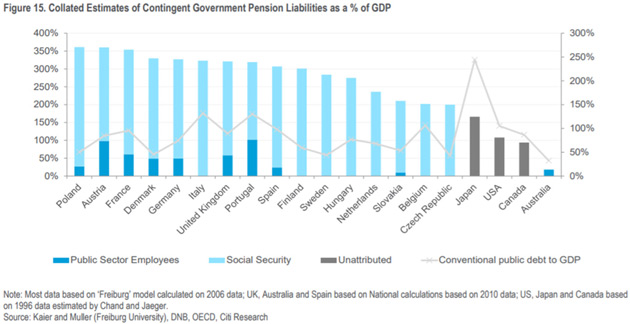

Source: Citi GPS Some research makes the above numbers seem optimistic. Most European economies are already massively in debt and have high tax rates. And those in the eurozone can’t print their own currency. French President Emmanuel Macron and a few others seem to be laying the foundations for the mutualization of all eurozone debt, which I assume will end up on the ECB balance sheet. However, that still doesn’t deal with the unfunded liabilities. Do they just run up more debt? It seems like the plan is to kick the can down the road a little bit further, which Europe is becoming good at. In this next chart, the line going through each of the countries shows their pension debt as a percentage of GDP. Italy is already over 150%. And this is an older chart. A newer chart would just be uglier.

Source: Citi GPS This problem is far bigger than even the most disciplined, future-focused governments and businesses can easily handle. It is not limited to any one country or continent. The problem exists everywhere, differing only in severity and details. Look what we’re trying to do in both the US and Europe. We think a growing number of people can spend 35–40 years working and saving, then stop working and go on for another 20-30-40 years at the same comfort level, all while fewer workers pay into the system each year. I’m sorry, but that is magical thinking at its worst. It is not what the earliest retirement schemes envisioned at all. They tried to provide for the relatively small number of elderly people who were unable to work. Life expectancies were such that most workers would not reach that point, or at least live only a few years between retirement and death. The simple fact is that the extended family, which was the source of support for those who were lucky enough to reach old age, has disappeared. As life expectancy has increased and the size of families shrunk since 1950, government has become the paternal/maternal caretaker of those who have reached the magical age 65. As I’ve pointed out in past letters, when Franklin Roosevelt created Social Security for people over 65, life expectancy was roughly around 56. US retirement age would now be around 82 if the retirement age had kept up with life expectancy. Try and sell that to voters. Worse, generations of politicians have convinced the public that not only is this possible, it is guaranteed. Many believe it themselves. They aren’t lying so much as just ignoring reality. But it does get them votes. They often outbid each other in political races to be the most generous. That’s not just at the federal level. It is more often seen at the local level promising ever more generous public services while filling all the potholes, too. They’ve made promises they can’t possibly keep, but the public arranges their lives assuming the impossible will happen. It won’t. How do we get out of this? We’re all going to make a big adjustment. If the longevity breakthroughs I expect happen soon (as in the next 10–15 years), we may be able to do it with less pain, but it is still going to require large and significant lifestyle changes. Retirement will be shorter but better, because we’ll be healthier. That’s the best case, and I think we have a fair chance of seeing it, but not without a lot of adjustment first. How we get through that process is the most important question. I’m not optimistic because compromise is becoming a lost art. Politics in both the US and much of Europe is an echo chamber where we mostly talk to ourselves and those who are like-minded. We ignore the other side, treating them as socially unacceptable lepers. We have lost the ability to disagree amicably and rationally. Not so long ago, Ronald Reagan and Tip O’Neill could sit down and work on Social Security. Bill Clinton and Newt Gingrich could sit down and not only modify welfare but balance the budget. Those days are gone. When some librarians think the children’s books by Dr. Seuss are racist and therefore unacceptable for a public library, the quality of civil discourse is spiraling rapidly downward. I do not like that, Sam I am. So much for staying home in June and July. I’m doing a one-day trip to St. Louis on Monday, then to LA in the middle of July to talk about the future of social organization with somebody I have long wanted to meet. Then I have the annual economics/fishing trip to Maine, then a board meeting with Ashford Inc. at the Beaver Creek Park Hyatt, where Shane and I will take an extended vacation, and then a trip to Boston to visit with friends in the area. My twins and their husbands are coming down next weekend to be with dad on their birthday, and they are getting the entire family together for sushi one night. I’m really looking forward to that. I struggled with this letter a little bit, as there is so much else I wanted to talk about. So many countries that have their own nuances that could fill a book, but my partners are trying to get me to write shorter letters, not longer. The truth is, retirement is going to be a problem everywhere. I left a longer piece on the cutting room floor about why extended lifespans are not going to be a problem, which I know many readers find hard to accept. But this is just one letter of seven (so far) of what will likely be at least a ten-part series. There are so many aspects to the debt crisis. I know we talked about pension problems in terms of 2050, but we will have to resolve these issues long before then. From a long-term perspective, this may be good news. The crisis will force us to face reality. It will be painful, but we know about it in advance. That means we can plan for it, and I really have a passion for helping people get through The Great Reset. We are all in this together. And with that, let me hit the send button. I want to wish you a great week. These next few months will be a period of big change for Shane and I—all the while, I am trying to write my book. But as Shane says, it’s all a new adventure! Your wanting that book gorilla off his back analyst,   | John Mauldin

Chairman, Mauldin Economics |

Share Your Thoughts on This Article |