In the equation 3 x 5 = 15, the 3 and 5 are factors, and 15 is the product. You can’t have a product without factors.

In economics we talk about “factors of production.” If you want to produce something, you need certain factors of production. These fall into four categories:

Land or natural resources

Labor: human beings who can work

Capital: money or other property that can finance land and labor

Entrepreneurship: ideas and risk-taking

The myriad goods and services the economy produces are all some blend of those factors. All four are necessary but today we’ll focus on labor, or as it’s sometimes called, “human capital.”

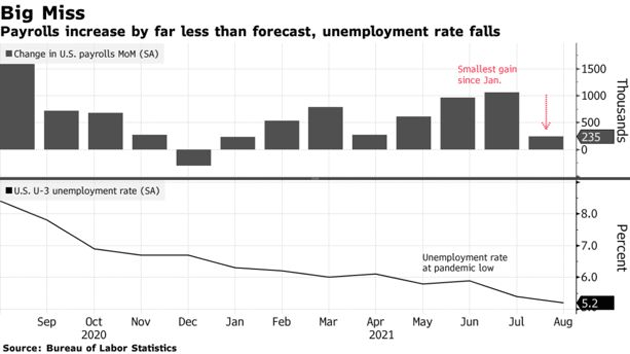

We are in an odd situation where it’s unclear if labor is scarce or abundant. Many employers can’t seem to find enough qualified workers, but the August jobs report said 8.4 million are unemployed and millions more underemployed. The unemployment rate dropped to 5.2%. Many employers are looking for workers but they only made 235,000 net new hires last month. The consensus estimate was 733,000, so a huge miss.

Source: Bloomberg

This is a big question with many threads. Today we’ll try to follow some of them.

First, a little rewind. When the coronavirus first struck last year and many businesses had to shut down, Congress added extra unemployment benefits. It also expanded eligibility to previously uncovered workers like the self-employed. These extra benefits later expired for a few months, then were renewed, renewed again, and now expire again this month.

For many workers the added benefits were actually more than they made when working, creating a potential disincentive to work. To what extent it actually did so is exceedingly hard to measure. Certainly some workers abused the system, but many others had legitimate reasons they couldn’t work.

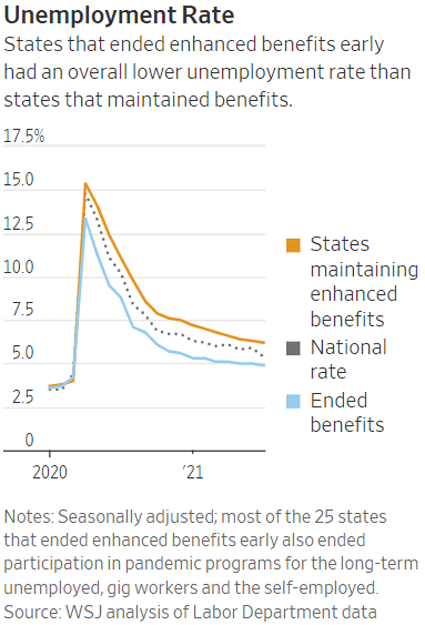

Nonetheless, some states decided to end the expanded benefits as early as June. Employment isn’t growing noticeably faster in those states—possibly because the worker shortages that sparked the move weren’t new. We had them before the pandemic, too.

Source: The Wall Street Journal

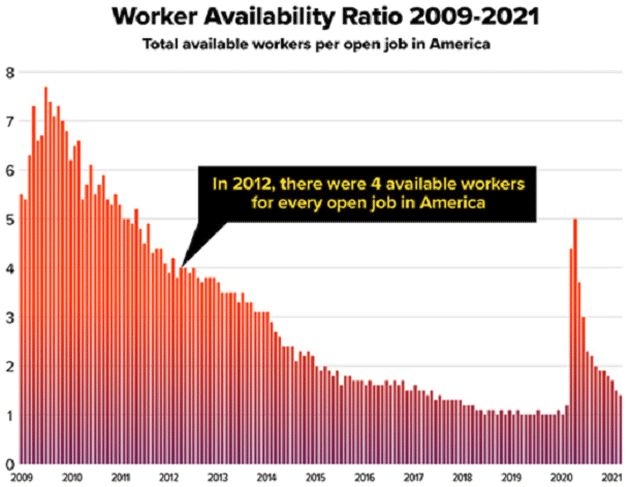

Here’s a US Chamber of Commerce chart with a different view of the employment picture. Using government data, they divided the number of job openings by the number of unemployed (“available”) workers to get a “Worker Availability Ratio.”

Source: US Chamber of Commerce

From the employer’s perspective, a higher ratio is better. It means there will be more applicants and more choices of whom to hire. But that same high ratio means, by definition, not enough jobs to go around. It also means too many people without a wage to buy your product. In an ideal world where every worker is qualified for every job, a ratio of 1 would be perfect. It would mean every job is filled and every worker has a job. But of course, it’s not that simple.

The chart shows the worker availability ratio steadily falling since the last recession when, not coincidentally, unemployment was at its peak. But notice it was actually lower in the couple of years before the pandemic than now. Think back to 2018/2019. Employers, and particularly small businesses, were desperate for qualified workers. The monthly NFIB surveys routinely listed it as one of the top challenges and now show it as a new record.

This “labor shortage” we attribute to COVID has been brewing for many years. The virus certainly made it much worse. It created new health concerns and gave people other reasons to change careers or stay out of the labor force. But none of this is new. What we’re seeing now is better viewed as a resumption of the previous trend.

So the real question is what caused that trend? Where have the workers gone? And has COVID made the trend even worse going into the future?

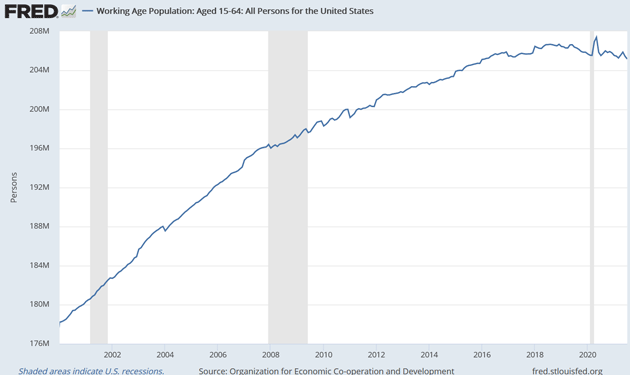

You’ll notice that worker availability chart shown above peaked in 2009–2010. That also happens to be when the Baby Boom generation began reaching age 65. Not all are choosing to retire—indeed, many (like me) are not—but the demographic winds changed about that point. Working age population growth slowed and, after about 2018, actually began falling.

Source: FRED

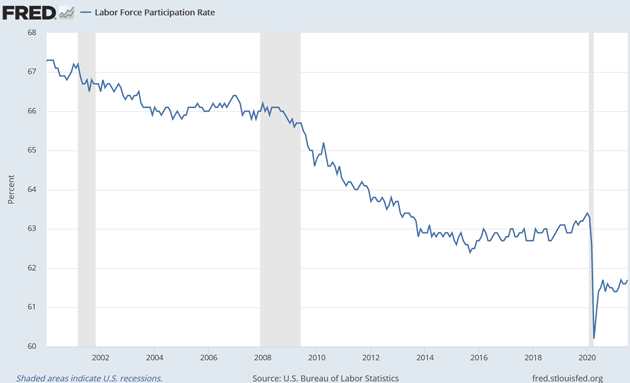

Worse, the percentage of this already-shrinking population who are available for work is also shrinking. The “Labor Force Participation Rate” measures the percentage of adults who either have a job or want a job. Some don’t because they are retired, full-time students, etc. So with Boomers retiring it has been on the decline, but even so, tried to stabilize in the 2016–2020 period. The pandemic ended that trend.

Source: FRED

The especially disturbing part here is that participation plunged quickly when COVID hit, then bounced back about halfway to where it had been, and has since been stable near that level. It’s starting to look like a “new normal.”

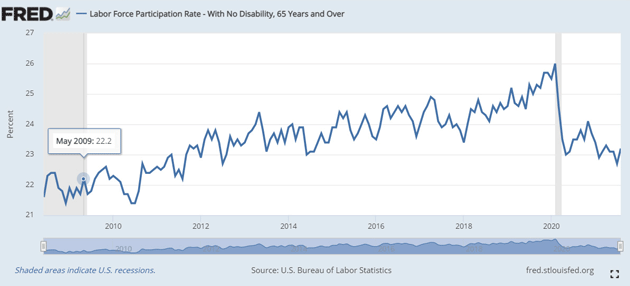

But one thing has changed. Prior to COVID, more older Americans (those 65 and older) were staying in the labor force. That trend has clearly changed. Let’s look at the chart:

Source: FRED

That’s the labor force participation rate, but what does that mean in raw numbers? Almost 1 million Americans aged 65+ dropped out of the labor force between February 2020 and July 2021.

Source: FRED

By raw numbers, looking at the total participation rate, we find that something like 3.5 million Americans of all ages who were in the labor force pre-COVID decided to leave it and haven’t come back. We know many decided to change careers and are now reeducating themselves. They will likely be back. The “working retirees” who are concerned about COVID risks may be back, too. But that still leaves the previous downtrend in the labor supply. What was going on?

That question brought to mind a 2017 letter I wrote called Men Without Work. I reviewed Nicholas Eberstadt’s then-new book of that same title, which explored the puzzling number of prime-age men who had simply disappeared from the workforce. We can point to many causes: poor education, opioid drug abuse, job outsourcing overseas, family breakdowns, and more, all of which play a role. I quoted Philippa Dunne who points to one specific factor.

As we shall see, a single variable—having a criminal record—is a key missing piece in explaining why work rates and LFPRs have collapsed much more dramatically in America than other affluent Western societies over the past two generations. This single variable also helps explain why the collapse has been so much greater for American men than women and why it has been so much more dramatic for African American men and men with low educational attainment than for other prime-age men in the United States.

This was and still is a big problem. My reaction to Philippa’s statement:

If we want to see things began to change, we going to have to deal with this “variable.” Perhaps we should rethink our concept of incarcerating everyone found guilty of using currently illegal drugs. Maybe we need to rethink about how long felony convictions stay attached to personal records. When you can’t even rent an apartment in many states because you were a felon, and in some cases simply because you were charged with a felony at some time in the past, is it any wonder that we have large numbers of people not participating in the labor force? With 20 million former felons in America, we have attached a large anchor to our economic growth rate, and we have unfairly burdened these men and women.

A silver lining to the current labor shortage is that employers are now reconsidering the wisdom of automatically ruling out this large group. They are realizing not all “convicted felons” are hardened, violent criminals. Certainly, some are. But many others were caught up in some situation or indiscretion, learned a lesson, and want to work. They just need a chance. Some are now getting one.

My Camp Kotok friend Jeff Korzenik, chief strategist at Fifth Third Bank, is very involved in releasing this “Untapped Talent,” and wrote a book with that title. He more or less stumbled on the problem as he met with executives of the bank’s industrial customers. They kept talking about hiring problems and drug abuse—not illegal drugs, but pain medications. That led him down a rabbit hole of economic cause and effect. It’s a swirling mess of drugs, prison, unemployment, and related ills, all feeding on each other.

I’ll share a few quotes from a fascinating interview Jeff recently did with Kate Welling. You can read the entire interview here.

JEFF: It’s potentially disastrous. An economy that has too few workers to grow at a robust pace isn’t just slower-growing. It is an economy forever teetering on the edge of recession. It limits access to credit. It is an economy that fails to engender the optimism to invest in training and productivity enhancements to build social wealth—and as we are seeing globally, slow-growing economies undermine confidence in capitalism, trade and free societies.

Adjusting the statistics for the age and sex of the US population only explains about half of the pre-pandemic decline in the labor force participation rate. I realized that we have to understand the reasons for this loss of American economic vitality if we are to have any chance of restoring our labor markets to their historic strength.

(JM: “Forever teetering on the edge of recession” is a good way to describe our economy. And we certainly see the “undermining of confidence” Jeff describes.)

JEFF: I know economies tend to move in cycles. They rhyme, if not repeat. But the data shows that the magnitude and the dispersion of the interrelated social problems now suppressing our labor force and sapping our economic vitality are unprecedented—making today wholly unlike past economic cycles, in kind, not just in degree.

KATE: To be specific, besides the opioid crisis, you are pointing to—

JEFF: Our entrenched long-term unemployment and the incarceration/recidivism cycle. Certainly one of the causes of the opioid crisis—something that permitted it to really take hold—was the big increase in the persistence of long-term unemployment arising from the Great Recession… Meanwhile, there is simply no precedent in US history for the labor implications of our incarceration/recidivism cycle.

KATE: What you’re saying is that all three of those complex problems are intertwined—and really crimp labor force participation—

JEFF: Yes, in the sense that the discouragement of long-term unemployment leads at least some to self-medicate and you get the opioid epidemic, and that the opioid epidemic then tends to lead to criminal justice system involvement. Then, around the time I was wrapping my arms around just how big these social problems are and how they are truly economic problems because of the way they depress workforce growth, I started meeting employers who were successfully offering second-chance hiring opportunities in their businesses.

John here again. This is a terrible problem and we are only beginning to address it. But COVID is bringing a new one. I heard Jeff speak passionately about this problem at Camp Kotok. If you are an employer or just want to understand the problem, you should read this book.

A few weeks ago, Dr. Mike Roizen and I wrote about “long COVID,” in which people continue showing symptoms long after healing from the disease’s acute phase. These vary tremendously in both kind and degree. Research is ongoing but it’s clearly a major medical problem. It will be an economic one, too.

To date, the US alone has had approximately 40 million confirmed COVID-19 cases, a number which is unfortunately growing as the disease reaches more unvaccinated people. More important, the latest cases tend to be younger and therefore more likely to be in the workforce.

Some studies show as many as 25% develop some degree of long COVID. It doesn’t seem related to the severity of their initial disease. Even mild cases can have debilitating symptoms months later.

Let’s estimate, I think conservatively, that long COVID afflicts 10 million working-age Americans over the next year or two. Some will be fully disabled, others mildly annoyed, most somewhere in between, but all will be rendered less productive.

Research is showing as many as 2 million of these people may go on disability or have their ability to work significantly reduced. Now think back to the equation I cited in my introduction. One of the factors of production was already getting smaller and long COVID could make it smaller still. This has a multiplicative effect, making Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth even more difficult.

Can improved automation fill some of the gap? Sure, but not all of it, especially since many of these disabled workers will come from knowledge-driven occupations that aren’t easily automated.

Further, COVID is once again clearly having an increased impact on services and travel. From Danielle DiMartino Booth at Quill Intelligence.

Citi’s weekly hotel report through August 28th reveals occupancy fell from 63% in mid-May to 44%. Revenue per available room (RevPAR) is off by 20.5% from its 2021 peak five weeks ago. While we know schools have reopened and seasonals matter, it’s still noteworthy that resort RevPAR is down by 39.7%. TSA throughput is at a three-month low and Open Table reservations are 10% off their highs. Google mobility also shows that at -6.3 vs. January 2020, time spent away from home at retailers and restaurants is at the lowest since mid-May.

This partially explains the almost zero increase in leisure and hospitality jobs in August, after huge growth in June and July.

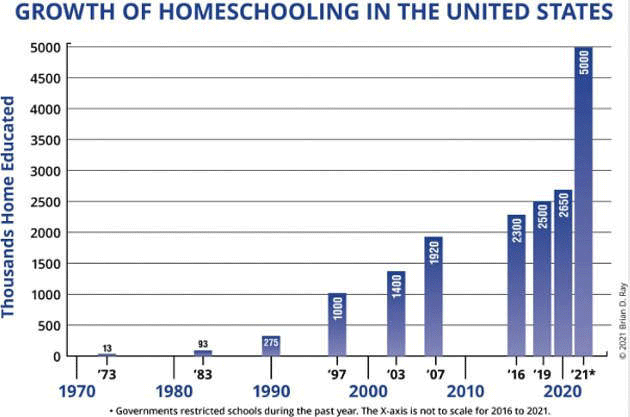

Here’s something that hasn’t hit the headlines. The number of people homeschooling their children has literally doubled in the last year, from 2.5 million to 5 million.

Source: Daily Mail

Source: Daily Mail

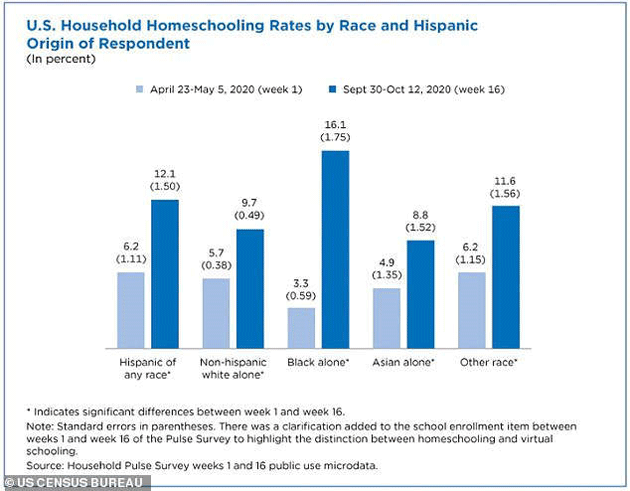

The increase was strongest among African-American households, which now represent 11% of US households, according to Bellwether Education Partners. Black households that are homeschooling jumped from 3.3% in 2020 to 16% today. This compares to 12.1% of Hispanic families now homeschooling, 9.7% of white families, and 8.8% of Asian families.

A significant percentage of the 2½ million new homeschoolers had at least one parent staying at home teaching. Not all were in the workforce before, but many were. All this is another giant challenge on top of the Perfect Storm potential I described last week. Mass unemployment and labor shortages are both problems, and we have somehow engineered ourselves into both at the same time.

Peter Boockvar had this succinct reaction to this week’s ADP jobs report miss (my emphasis):

…While Delta is the excuse now for a more uneven recovery, the inflation and supply problems are as well and I believe the predominant factors. Labor particularly is in short supply as we know and in turn is limiting hiring. We also must begin to think of the scenario that the labor market is much tighter than previously thought with just about every company talking about the difficulty in finding people. The belief that we're going back to a pre-Covid labor force is just not realistic as too much has changed and the Fed's goal of maximum employment defined as that pre-Covid situation is just not a goal that can be achieved.

This is more than just a jobs problem. The Fed is looking for the economy to reach some mythical level of “maximum employment” before it starts normalizing policy. The expectation they will start tapering by year-end made sense two months ago. Now? Not so much. They will use the weak jobs data as an excuse. And that, in turn, leads to a variety of other challenges.

As Peter says, “too much has changed.” I agree but we don’t really know what changed, or whether the changes are over. Samuel Rines sent a thought-provoking letter this week noting some labor market oddities. Unlike the Great Recession, which had a greater effect on male employment, COVID saw women affected more (homeschooling?). He points to Pew Research data suggesting mothers of young children are less likely to be in the labor force. If so, it would be a major reversal of the last few decades.

Lower participation by both women and older Americans would be a major dent to the labor supply, and may explain some of the current situation. These are personal choices that vary by circumstances, but they’re clearly happening.

And now we come full circle to the math lesson at the beginning of the letter. GDP is equal to the number of workers times productivity. Two factors. If we reduce the number of workers by a combined 3 to 4 million, which is well over 2% of the total potential workforce, you also reduce GDP by 2% unless productivity dramatically increases.

That might make even the 1% real GDP growth I’ve been expecting hard to reach in 2022 and going forward.

On a quick note that deserves its own letter…

If the Federal Reserve looks at this lower unemployment data while not taking potential workforce shrinkage into account, they can justify (to themselves, at least) keeping monetary policy softer for longer than it should be, risking more extended inflation.

Actually, it’s worse than that. They are risking stagflation. I noted early in this pandemic era that, like the Great Depression, it would bring unforeseeable long-term changes. They are starting to show themselves, but only as fuzzy outlines.

We know something big is coming. Exactly what it is, only time will tell. Hopefully you and I can put the pieces together.

I am making a last-minute trip to Palm Beach to meet with my old friend Pat Cox and a number of scientists about some breakthroughs in longevity. Then back Sunday. There are so many incredible things happening in the gerontology world. I really do try to stay up on what’s going on.

I had many more charts and articles that just didn’t make this letter, ending up on the editing floor. Wages were up across the board and significantly. There are other smaller factors suggesting labor could get even tighter. Trying to keep track of it all is stretching my time management skills. You should follow me on Twitter. I have a lot of fun, even when I stir things up.

Thanks for reading me and please feel free to forward this and any letter to your friends. An endorsement from a friend is the ultimate in writing satisfaction. It’s time to hit the send button so have a great week!

Your planning to live much longer analyst,