I am ecstatic to bring you David Bahnsen as a special guest writer. He is on TV somewhere nearly every day (all the networks love him) and the host of National Review’s “Capital Record” podcast. My relationship with the Bahnsen family goes back 40+ years, as I published his father’s theological commentaries (Greg Bahnsen) in the ‘80s. Greg unfortunately left us early and David had to put himself through USC, start from the bottom, and now runs almost $4 billion dollars as an investment advisor. We have similar views on money management and today he’ll give you a powerful lesson on growing assets in volatile times.

By David Bahnsen

First, I must say this is an absolute thrill. I began reading Thoughts from the Frontline every week in 2001 and have benefitted immensely from this weekend routine ever since. I have always learned from John’s perspective, even in occasional disagreement, and know John to be a vigilant student of markets and economic reality.

Years ago, my relationship with John transcended merely reading his books and newsletters, and we became close friends. Our dinner conversations have become the stuff of legend, both for the size of the bill and the hours logged at the table, but also the depth and breadth of discussion. Iron sharpens iron, and there is little I enjoy more than sharpening iron with John and other mutual friends over veal chop, pasta, or steak. I am a more careful student of markets because of John. In short, he has been a teacher and friend, and I am as grateful for these last 20+ years as I am this opportunity to write.

A big theme of John’s when I first found Thoughts from the Frontline as well as his book, Bull’s Eye Investing, was a “muddle-through economy”—this idea that we would not enjoy robust post-war economic growth levels in the new millennium, but neither would the economy entirely destruct. Straight recessionary investing is one thing; uninhibited expansion is another; but the “muddle-through” concept required a different approach, including the implementation of “alternative investments.”

The term “alternative investments” was hardly mainstream when John began writing about this. I believe the term “alternative investments” to refer to those investments designed to mitigate the shortcomings of Modern Portfolio Theory. “60/40” has filled an effective purpose through much of investing history, but the “muddle-through” period John described warranted additional diversifiers—additional hedges—non-correlated approaches that may further an investor’s accumulation needs.

I continue to believe, today, that alternatives have a vital role in contemporary portfolio construction. The reasons may have changed a bit since the Mauldin/muddle-through conversation’s early days, but the benefits of diversifying a portfolio with strategies that are non-correlated to traditional, long-only stock and bond indices remain. There is a troubling tendency to view alternatives as “that which will make money even when nothing else is”—as if the term is a sort of magic potion that produces magical returns when markets are struggling.

Those who hold this expectation don’t abandon it when markets are doing well. In other words, an “alternative investment” to so many people is supposed to be “that which makes money when markets are doing well, and that which makes money when markets are not doing well.” It sounds dreamy. I have yet to figure out why, if it were so simple, one would allocate only 20‒30% there. Indeed, a 100% allocation would make sense for such a calorie-free version of delicious food, no?

I suggest a better definition for alternative investments is “the replacement of investment risk from that of market beta to that of manager decisions.” The idiosyncratic nature of alternative investments may diversify away systematic market risk, but can’t off-load the very real risk of manager selection, manager timing, strategy wisdom, or specific execution. Now, a portfolio with a fair amount of equity beta risk, bond interest rate risk, and idiosyncratic manager decision risk may very well be a better portfolio than one with only the first two components (I would argue that it is), but it does not become a risk-free portfolio. It alters the risk, and does so for the aim of (fallibly) trying to improve the risk-reward trade-offs in a complete portfolio.

My passion for alternative investments started off with reading John Mauldin’s thesis of a Muddle-Through Economy. I was deeply influenced by Alexander Ineichen’s Fireflies Before the Storm at UBS (where I started my financial career over 20 years ago). Rather than viewing alternatives as a magical asset class , it became very important to me to view alternatives as asset managers . This clarifying distinction served me and my clients well the last two decades. I have seen Wall Street do everything it can to market products over the years, almost always when retail investors were looking for something to provide the illusion of safety they craved, but I have never fallen for the delusion that returns can come without risks. I have simply tried to define and understand the risks I am taking as much as possible. Alternative investors have to do this with a rooted view of reality, and humility.

The third phase of my evolution with alternative investing has been the need to diversify fixed income allocations. In the equity crash that followed the tech bubble burst of 2000, many viewed alternatives (hedge funds, managed futures, real estate, commodities) as a diversifier to equity risk because it was equity risk that had just slapped their portfolio upside the head. The next time an equity diversifier was needed (late 2007 through early 2009) alternatives created mixed results with high dispersion (that is, some managers did well, some didn’t). This was not an indictment of the alternative investment industry but rather what was merely inevitable. Again, though, the general conversation almost always centered around alternatives to replace equity risk. While non-agency mortgage bonds got slaughtered during the financial crisis, straight Treasury bonds did exactly what 60/40 asset allocators banked on—yields collapsed and prices advanced, diversifying the pain of the equity crash.

But the 10-year Treasury bond yielded over 5% in the summer of 2007. It was half that when markets bottomed in March 2009. Put differently, the inverse correlation of stocks and Treasuries worked quite well. Corporate bonds, municipal bonds, and certain mortgage bonds didn’t keep their end of the bargain as well. The equity pain was impossible to perfectly diversify, but again the 60/40 concept was at least theoretically intact.

| [Buffett’s $51 Billion Buying Spree] After years of sitting on the sidelines, Warren Buffett is buying up billions in stocks. That’s all thanks to a rare market “imbalance” returning for the first time since 2009. Click here now for the full story. (From Our Partners.) |

My focus today for larger allocations to alternative investments has much more to do with diversifying fixed income than diversifying equity volatility. We are sitting today on the precipice of a recession with the Fed raising rates, and the 10-year Treasury yield at 2.7%. When we entered the COVID moment the 10-year had a one-handle, limiting the bond market’s ability to provide much portfolio offset. The asset allocation benefit that Treasury bond investors received even then was limited to US bond investors, as European sovereigns and Japanese government debt was already at the zero-bound, leaving no room for portfolio defense. Our yield curve is inverted, and even when it normalizes it is likely to stay quite flat for a long time.

Our own government cannot afford a short end of the curve much higher than it is now, and our own fiscal and monetary decisions have held down the long end of the curve in what I believe is a multi-decade period ahead that is best referred to as “Japanification” (I stole that term from John; I just don’t know if or where he stole it). [ JM—I don’t either .]

In the years ahead, Treasury bonds do not appear likely to deliver the diversifying benefits they have historically provided. This is not saying “this time it’s different” in concept. A bear market selling of equities would likely see money flood into Treasuries pushing yields down and prices up. But it is saying “this time it’s different” in math! A 2.5% starting point is not the same as starting at 5%.

So as an asset allocator who has historically assumed some 5‒10% return from Treasuries when things go really bad, and as one who believes most investors behaviorally need a diversifier to the reality of equity beta, I have increasingly used alternatives to try and fill some of that void that bonds are less likely to fill. I have not done so with a naïve optimism that all alternative strategies possess the “flight to safety” benefit of Treasuries. Quite the contrary, I assume there will be difficulty in good times and bad times with certain idiosyncratic exposures because, well, they are idiosyncratic. But I remain confident that proper due diligence and a focus on manager process, risk management, and alpha generation can be a truly special diversifier both on the offensive and defensive sides of the field.

But I digress. Despite the numerous opportunities for equities to disrupt investor dreams from 2009‒2021, the reality is that in those 13 calendar years the S&P 500 had exactly one negative return year, and it was a rounding error (2018)! Plus, 2017 and 2019 were so darn good many equity investors don’t even remember 2018 was technically down a few points. P/E ratios went up, a lot. Underlying earnings went up, a lot (permabears missed this). The Fed poured liquidity all over the place. Risk-taking came back in spades and significant financial repression served as a “put.” For US-centric equity investors not only was equity beta itself generally a great trade, but it happened to be far superior on a relative basis to competition from European or emerging markets, each struggling for different reasons.

John writes so capably every week about the Fed, about recession risk, and the plethora of macro complications that we face, I want to keep my major takeaway to something different. One does not need to settle the inflation vs. deflation debate or the recession vs. slowdown debate to say this: Equity valuations, highly embedded monetary instabilities, and excessive sovereign indebtedness all point to a more difficult decade ahead for index investors than the decade they just finished enjoying. One does not need to be a permabear to make this point. In fact, one could almost say “muddle-through” is the optimistic case here and wouldn’t be too bad if it ended up happening!

But I will suggest a replacement to S&P broad market index investing that represents a far superior alternative to the equity allocation of today’s investors, both those accumulating assets and those withdrawing from their portfolios. I will suggest this niche aspect of equity markets has not only been the right medicine for many decades behind us but is uniquely appropriate now.

Instability in monetary policy is not going anywhere. You may believe, as John does, that Jerome Powell would rather be the next Volcker than the next Bernanke (that is, rates are going higher than people think). Or you may believe, as I do, that Powell will talk inflation-fighting all he can, but deep down he is programmed to be an anti-deflation central banker who is keenly aware that the federal government can’t service its $30 trillion of debt at a 5% fed funds rate. I don’t believe investors need to solve the inflation vs. deflation fight if they are willing to say, “both.”

The Fed’s legitimate purpose as a “lender of last resort” is long, long gone, and its Congressionally sanctioned “dual mandate” for price stability and full employment is also gone. Today, the Fed exists to sooth that which ails us, and this wholly inappropriate reality is sure to add to the instability of a world already reeling in trillions of dollars of sovereign debt. The old view that the Fed was there to bail out Wall Street is antiquated. Main Street would no longer tolerate a Fed not there to serve up goodies when the going gets tough. But alas, the Fed cannot defy the laws of math, science, or economics. The result is an increasingly unstable monetary framework and the exacerbation of boom/bust cycles that the Fed has created. Rinse and repeat.

Why is dividend growth immune from this? I didn’t say it was immune—especially not if one means “immune from price volatility.” But I do believe it is far more practically protected than conventional index investing. Let’s start with just the valuation discussion.

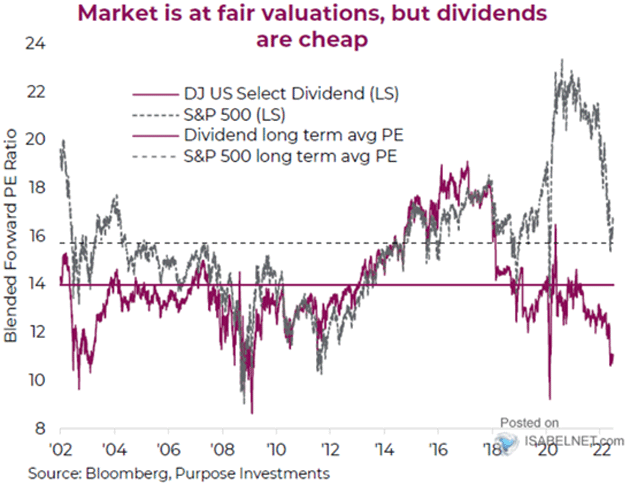

I take exception to the idea that the forward valuation on the S&P at 17X is a “fair valuation”—primarily because I question the current forward earnings estimates used in the math. But as it stands now if $250 is still the approximate forward earnings estimate, 17X is roughly the forward multiple on the S&P (compared to a 16X average). But the dividend stock index, despite substantial outperformance over the S&P 500 this year, still trades at a significant discount to its own historical valuation.

Source: Isabelnet.com

How is this possible? Simply put, in the short term stock prices are voting machines, and people love technology stocks. People love growth stocks. People love returns that can’t possibly be sustained because it lets them believe trees can grow to the sky. People love the idea that a 15‒20% annual return can come with no real downside risk. Apple and Tesla are sexy; Procter & Gamble and McDonald’s are not.

But sexiness or lack thereof does not change the fact that McDonald’s has outperformed the S&P 500 by over 3% per year since SPY was created (with a higher Sharpe ratio, for those curious about volatility). It also does not change the fact that the current $5.50 annual dividend is equal to the share price of McDonald’s when I graduated high school 30 years ago. Yes, the cash-on-cash yield is currently 100% per annum for those who bought and held MCD in 1992.

Am I cherry-picking with McDonald’s? Not exactly. A slew of familiar names from Johnson & Johnson to Walmart to Coca-Cola are similar. My point is that for those accumulating assets for the future, a properly constructed portfolio of dividend-growing companies has created a significant total return, with generally lower volatility than the market, and that those needing to withdraw from their portfolios can do so in a straight line up, unimpeded by the inconvenience (and mathematical danger) of withdrawing from a declining asset.

I mentioned earlier that John’s muddle-through thesis sold me on the need for alternatives in a portfolio over 20 years ago. At the same time, the results of withdrawing from an index portfolio during the 2000‒2002 drawdown convinced me of the need for a better withdrawal strategy. A bland asset allocation of ETFs or mutual funds with the standard fare of large and small cap and growth and value may create an adequate return, but it does the investor no good at all if their portfolio is not there to receive that adequate return. Selling assets as they decline (as all withdrawers from an index portfolio must surely do at some point in their investing career) will permanently deplete capital. Withdrawing only from the fruit of a tree (that is, taking the dividends that do not decline and leaving the stocks alone that go up and down in price while generating the dividends) will not.

I believe equity investing is the attempt to capture the risk premia from a profit-creating enterprise. I, like John, believe in free enterprise. I am long humanity and desire to be long the public equities that so often will capture much of humanity’s success. There will be failures, too, hence the need for diversification and proper management, but dividend growth equity ownership is easy to understand: capturing the profits that come from the innovation, creativity, and execution of great companies. When one focuses their selection on free cash flow generation, on a true cultural propensity to share profits with shareholders, and on stewarding a balance sheet that makes these procedures repeatable and protected, they de facto de-risk their portfolio. They free themselves from the unspoken curse of the index investor— the reliance on multiple expansion for returns.

Valuations have cooperated for 12+ years. When we look into the next 10‒12 years do we see significant multiple expansion? Do we see significant new avenues of Fed stimulus and risk asset coddling?

I don’t. But I see companies that manage to a shareholder return ethos being far better protected from the instabilities of Fed policy. I see free cash flow and balance sheet strength mattering, a lot. I see less reliance on risky (or bad) M&A. I see the sharing of profits in the form of cash payments being a qualitative and quantitative benefit to those who take the risk of equity ownership. I see the paltry 1.5% dividend yield of the S&P 500 now and a 10-year bond only 1% or so higher than that, and I believe a diversified dividend portfolio yielding 4% or so is doable, needed, and superior.

I don’t know what Jay Powell is doing for the next 10 years. But you know what? I feel pretty good about what Ronald McDonald is going to do.

I am not getting great news for my first few days at the Cleveland Clinic. Difficult lifestyle changes are in front of me. Sigh. But we do what we must. Much better to look forward to salmon fishing in British Columbia. And to a new business venture in the oil patch, which I hope to announce in a month or so. The ESG movement is handing investors a fabulous opportunity and I hope to allow us to take advantage of it together.

And with that, let’s hit the send button and wish you a great week. I’ll be back at the writing desk next week. And make a point of following me on Twitter and telling your friends to do so as well. A referral is the greatest compliment.

Your ready for some changes analyst,