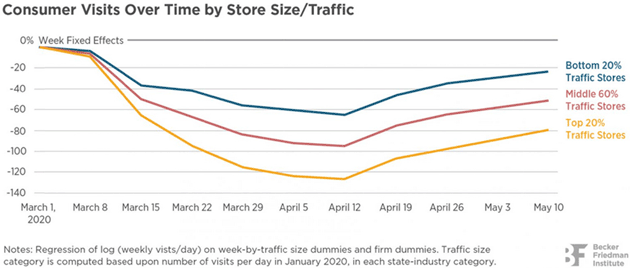

Small Business Blues By John Mauldin | Jul 18, 2020     Politicians love saying small businesses are important to the economy. In this case, it isn’t just rhetoric. The millions of little companies with a handful of workers are, collectively, more important than the few hundred large enterprises we see in the news. That’s one reason the corona crisis has been so economically devastating. It hit hardest the small businesses that are both critical to growth and vulnerable to disasters. Yes, I know, some large businesses have been eviscerated (e.g., airlines) but small business have been hit harder. Furthermore, the policy responses haven’t been especially helpful or equal, either, and possibly harmful. This will have wide-reaching, long-term effects. Today we will discuss them. I should mention, I’ve been one of those small business owners or managers my entire career. I know how it feels when employees are like family (or perhaps literally are), the desire to protect them as any parent or friend would, and the agony when you can’t. This situation hasn’t just cost jobs and income. It’s killed hopes and dreams. The good news: Dreams are a renewable resource. We can replace the lost ones. We’ll talk about that, too. The New York Times has many issues but its writers excel at finding personal examples to illustrate broader stories. Though this time, they didn’t have to look hard. On the last Friday of June, after Gov. Greg Abbott of Texas said that bars across the state would have to shut down a second time because coronavirus cases were skyrocketing, Mick Larkin decided he had had enough. No matter that Mr. Larkin, an owner of a karaoke club in Wichita Falls, Texas, had just paid $1,000 for perishable goods and protective equipment in anticipation of the weekend rush. No matter that the frozen margarita machine was full, that 175 plastic syringes with booze-infused Jell-O were in place, or that there were masks for staff members and hand sanitizer for guests. That day, June 26, Mr. Larkin and his partner dumped what they had just bought into the trash and decided to close their club, Krank It Karaoke, for good. “We did everything we were supposed to do,” Mr. Larkin said. “When he shut us down again, and after I put out all that money to meet their rules, I just said, ‘I can’t keep doing this.’” Mick Larkin’s only mistake was owning a business that combines crowds, drinking, and singing, all of which help spread respiratory viruses. Now, he’s done. And he’s not the only one. For nearly two decades, Rich Tokheim and his wife sold sports memorabilia—hats, T-shirts, coffee mugs, and other trinkets—to fans in Omaha at their store, The Dugout. Since 2011, The Dugout has occupied prime real estate across the street from the city’s 24,000-seat baseball stadium, which usually hosts the College World Series each spring. The 2020 World Series was canceled in March. In the weeks that came after, other sporting events were scrapped—starting with college sports and extending to professional leagues that have struggled to relaunch their activities. Mr. Tokheim, 58, watched his business fall off with growing unease, but it was only after a friendly chat with a retired college athletic director in May that the gravity of his situation hit home. He was already worried about the state of the virus in Nebraska, and whether there was enough tracking. Then the athletic director predicted that if college football was canceled for the year, it would be the end of Division I sports as a whole. “That really put me in overdrive,” Mr. Tokheim said. He negotiated an early exit on his store lease and announced a clearance sale at the store. The Dugout closed for good on June 30. And another one: Many small businesses are also finding it onerous to keep up with constantly changing local guidelines, while others are deciding that no matter what their local officials say, it just is not safe to keep going. Gabriel Gordon, the owner of a tiny but popular barbecue restaurant in Seal Beach, Calif., decided to close permanently after studying the restaurant’s layout. He had determined that the kitchen would never be safe for multiple staff members to occupy at once while the virus was still active in the area. “It’s essentially two hallways that are 11 feet wide,” Mr. Gordon said, describing the shape of the restaurant, Beachwood BBQ. “There are food trucks that are larger than my kitchen.” Those are just three of many tens of thousands. The owners did everything right. In any other circumstances, they would be providing jobs and helping their local economies grow. Now they’re out. The NYT article mentions Yelp estimates that 66,000 small businesses will never reopen, and then cites a Harvard study which estimates 110,000 small businesses have shut down permanently. What is causing this? It’s not entirely government orders. A study from the University of Chicago’s Becker Friedman Institute used mobility data to measure foot traffic at 2.25 million US businesses. Traffic fell significantly weeks before shutdown orders took effect.

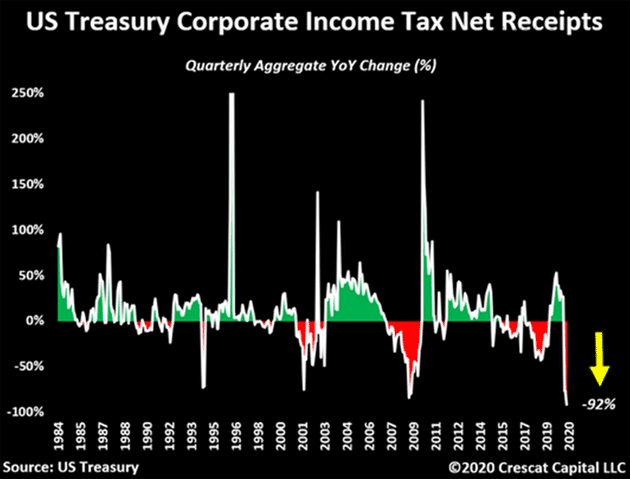

Source: Becker Friedman Institute The mobility data was not only granular enough to compare similar businesses in the same area, it compared businesses across county lines or city limits at which the legal restrictions changed. The businesses in places without shelter-in-place orders had only slightly higher traffic. In other words, consumer choices are driving this, not governments. And that’s something every business owner understands. I don’t know any bar owner who wants people to risk their safety or health. The problem is when your entire business model is suddenly perceived as hazardous. Small business owners succeed by laser-focusing on their strategies. They aren’t, and shouldn’t have to be, public health experts. They just need to know what is required to operate safely. And, after the initial March/April closures, most were allowed to reopen with various modifications. So, acting in good faith, many did (but not all, as we’ll see in a minute). The National Federation of Independent Business does a monthly “optimism” survey. Its members’ moods perked up considerably in June. Owners reported improved sales outlooks and said they anticipated better business conditions in the coming months. But NFIB collected that data in June, when we now know virus cases were just beginning to resurge in some states. Texas Governor Greg Abbott ordered bars to close on June 26. Other restrictions returned as July unfolded. So the optimism NFIB found is disappearing fast, at least in parts of the US. (Here in Puerto Rico the government restored many restrictions yesterday.) We talk of a second virus wave, but it’s an economic second wave, too. New orders are hitting businesses still trying to rebuild from the first one. But again, it hit businesses indirectly. The real problem is consumers choosing to stay home and buy only essentials, often ordering online. Small businesses feel it when even a small percentage change their behavior. In theory, this shouldn’t have been a problem. Washington responded quickly (and at near-lightspeed, by government standards) with Congress passing the CARES Act in late March. It included, among other things, a “Paycheck Protection Program” to help small businesses avoid layoffs and survive the shutdown period. Unfortunately, PPP didn’t work as envisioned for many businesses. The application process seemed simple enough but even simple things are hard when you’re struggling just to stay afloat. Then the initial funding tranche ran out quickly. And then the well-intentioned restrictions on how businesses could use the money kept it from helping some, particularly those in high-rent areas. By the time all that started to get sorted out (and it’s ongoing even now), many small business owners had given up, or had already laid off the workers whose paychecks the program was supposed to protect. Worse, the number is still growing. Many small businesses serve individual consumers but just as many provide services to large corporations. It’s no secret that large corporations are struggling. You can see it from corporate tax receipts which are down 92% in the last year (hat tip to Lance Roberts). Corporations cutting back every possible cost means less money spent at small businesses.

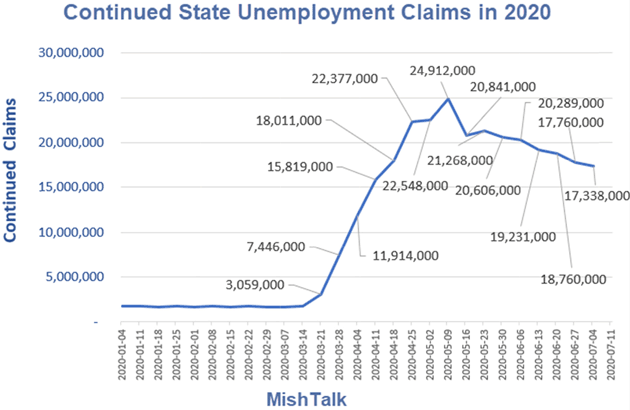

Source: Crescat Capital Further, Mike Shedlock at Mish Talk gives us the most recent data (as of Thursday) on unemployment. This needs a little technical setup. States pay unemployment insurance. That’s what you see in the data on new applications for unemployment and continuing claims. But that’s not the whole picture. The CARES Act complicated the jumble of federal and state unemployment programs. Here is Continued State Unemployment Claims. It’s like it’s beginning to trend down. Yay home team.

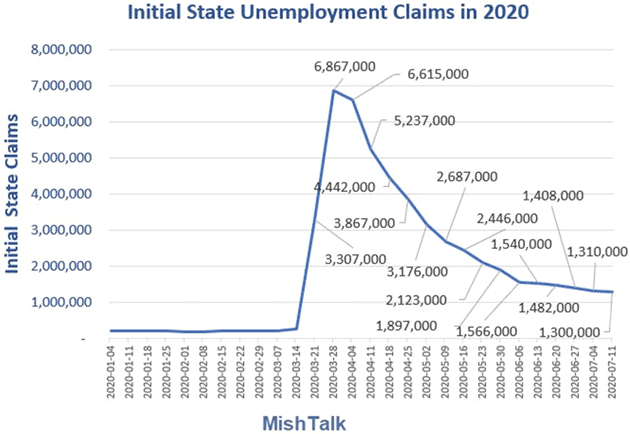

Source: Mish Talk It looks even better if you are looking at Initial State Employment Claims for 2020. Clearly the trend is down, although it flattened in the last few weeks.

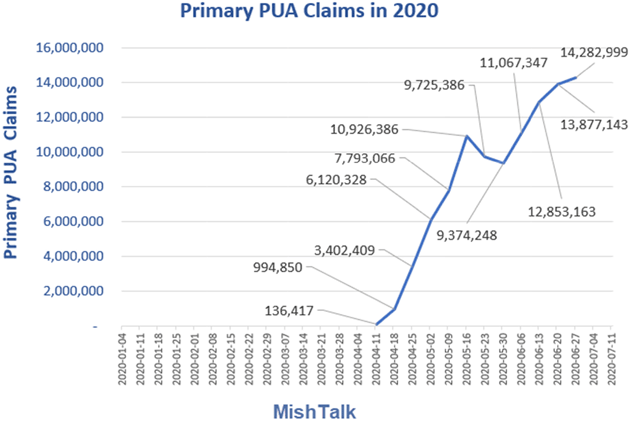

Source: Mish Talk That’s all well and good until you add in the federal numbers. Then the picture becomes markedly uglier. As Mish says, any improvement at the state level looks like a mirage. Here are the claims for federal unemployment:

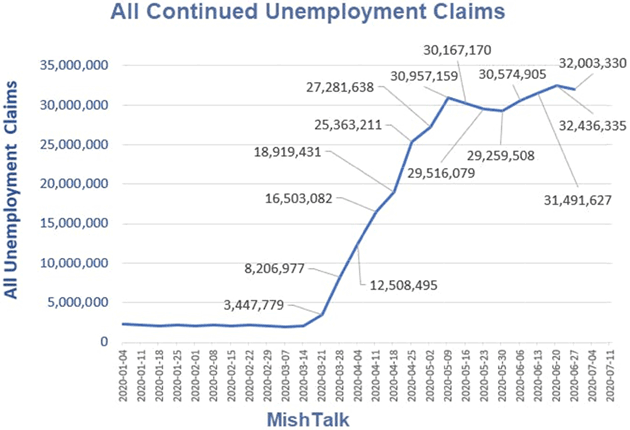

Source: Mish Talk On a phone call with Mish, asking for clarification, he pointed out that the data above has a reporting time lag of two weeks. As you can see, the trend has clearly been accelerating since early April or the initiation of the program. It is probably not unreasonable to assume that we will find out in two weeks there are an additional 1.4 million unemployed workers. So what happens when you add all these unemployed numbers together? You get a chart labeled All Continued Unemployment Claims:

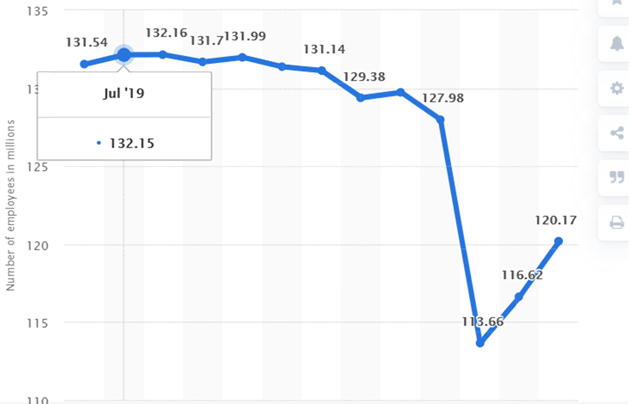

Source: Mish Talk Let’s see what that 32 million unemployed workers means to the employment picture. The US had 132 million full-time workers at last year’s peak.

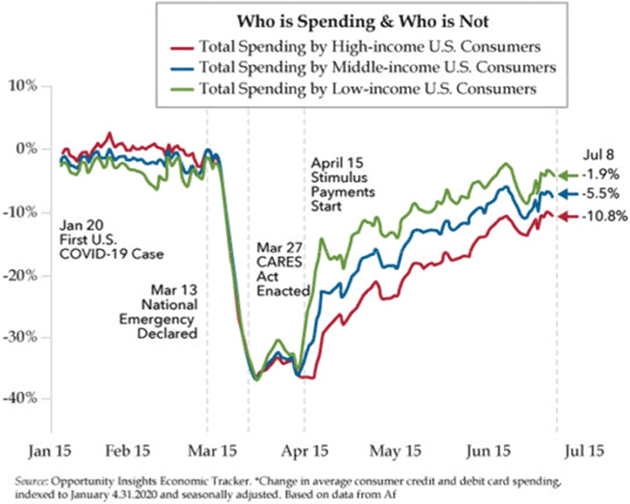

Source: Statista Pew Research tells us that “more than 157 million Americans are part of the U.S. workforce,” which would include those who are working part-time. Some part-time workers do not qualify for unemployment insurance either at the state or federal level. That would mean a best-case unemployment rate of almost 20%, but if unemployment claims are skewed to full-time workers, which they likely are, unemployment is closer to 23% including lost part-time jobs. These workers are generally spending less money, but wait, it may/will eventually get worse. Sigh. I don’t know what it is about Danielle DiMartino Booth, but her Quill Intelligence newsletter usually hits my inbox while I am finishing my own letter. And it always seems to have a data point that is absolutely on target with what I am writing. Today was no different. Note how those in the highest income ZIP Codes are spending less.

Source: Quill Intelligence That spending by the lowest income brackets will disappear if the $600 per week federal unemployment benefit is not extended after July 31. Quoting Danielle: As we’ve written in the past, the top two quintiles of income earners in America account for 61% of spending, or 42% of GDP. If they don’t spend, the economy comes to a screeching halt. As you see, as of July 8, spending among high-income earners was off by 10.8% compared to -1.9% for the lowest income earners. J.P. Morgan’s findings not only square this circle but stand as a stark reminder for lawmakers duking it out on Capitol Hill: “While aggregate spending of the employed was down by 10%, the spending of unemployment benefit recipients increased by 10%, a pattern which is likely explained by the $600 federal weekly supplement. At the same time, our second finding is that among the unemployed who experience a substantial delay in receiving benefits, spending falls by 20%.” We’ll translate—if the unemployment insurance supplement is not extended full board, the hit to spending will be immediate. If you are in the restaurant business, that brief ray of hope has disappeared. After seeing a high point of -49.8% nationwide year over year on July 2, OpenTable reservations are back down to -64%. With the closures in Texas and other states, that will not improve in the next few weeks. I think it is highly likely the extra unemployment benefits will be extended, at least until the election. But at some point, the country simply cannot afford to pay people $30,000 a year. Democratic candidate Andrew Yang’s $1,000 per month idea seems like small potatoes now. The national debt is $26.5 trillion and will be $30 trillion sometime in 2021. Ugh. Today we sent Over My Shoulder members an annotated version of Lacy Hunt and Van Hoisington’s latest quarterly letter. I’ll quote from the introduction, though you should look at the entire piece. Read it three times and then meditate. Then try to figure out where V-shaped recovery beliefs come from. Four economic considerations suggest that years will pass before the economy returns to its prior cyclical 2019 peak performance. These four influences on future economic growth will mean that an extended period of low inflation or deflation will be concurrent with high unemployment rates and sub-par economic performance. First, with over 90% of the world’s economies contracting, the present global recession has no precedent in terms of synchronization. Therefore, no region or country is available to support or offset contracting economies, nor lead a powerful sustained expansion. Second, a major slump in world trade volume is taking place. This means that one of the historical contributions to advancing global economic performance will be in the highly atypical position of detracting from economic advance as continued disagreements arise over trade barriers and competitive advantages. Third, additional debt incurred by all countries, and many private entities, to mitigate the worst consequences of the pandemic, while humane, politically popular and in many cases essential, has moved debt to GDP ratios to uncharted territory. This insures that a persistent misallocation of resources will be reinforced, constraining growth as productive resources needed for sustained growth will be unavailable. Fourth, 2020 global per capita GDP is in the process of registering one of the largest yearly declines in the last century and a half and the largest decline since 1945. The lasting destruction of wealth and income will take time to repair. The same legislation that created PPP authorized the Federal Reserve to lend to larger companies. It has been buying corporate bonds in the secondary market, which basically means many public companies can get low-cost capital just by making a bond issue. Such loans aren’t forgivable like PPP, but they have fewer strings attached. That’s one reason large businesses are generally enduring this period better than small ones. They tend to have deeper pockets, more access to financing, and are better able to implement safety requirements. Their scale lets them demand better terms from suppliers and landlords. A small restaurant owner might go to their landlord and ask for lower rent. The national chain simply says, “We will pay this much” (which might be zero) and dares the property owner to sue. The likely outcome, once we get to the other side, will be more consolidation, less innovation, and the continued presence of zombie companies that in other circumstances wouldn’t survive. I can’t tell you how sad this makes me. The dynamism and staggering variety of our small businesses is a prime reason the US has led the world. Millions of people implement millions of ideas every year. Most don’t work, but some do and they make our lives better. We will feel this loss for generations. This is the opposite of Schumpeter’s creative destruction. Let’s call it noncreative protection. The whole concept behind Schumpeter’s thesis was that smaller companies, or new technologies, and so forth would come along and provide better services, thereby taking away the business of large companies and in some cases simply killing them. But the economy and consumers would win. Now we are trying to save those large companies. Some deserve it, I’m sure. But which ones and how many? You may remember Global Crossing. In the 1990s investment mania, it spent billions of dollars on undersea data cables, connecting the world. The data didn’t materialize fast enough, and Global Crossing went bankrupt. The new owners used the now-cheap assets to sell lower-cost connectivity. Huge losses for those investors, for which we should all be grateful, helped fund the era of cheap international communications. The same happened with railroads in the 1870s. There was a mania by states and local governments to fund railroads connecting their cities and states. Every one of them went bankrupt, with the exception of one privately funded company (another story for another day about government programs). The bankrupt railroads with new owners offered cheaper travel which opened up the West. The point is, keeping companies from going bankrupt is not always best for consumers and the economy. Now we are in different times. This is a crisis of unbelievably different and epic proportions. But the current “mania” to save all large businesses because they represent jobs should not become a habit. Fighting Mother Nature—or creative destruction—is not a good practice. I want to end with a suggestion. Especially if you are retired, think about small, independent businesses where you spend money. Maybe a favorite bar or restaurant, a retail store, barber shop, or anything else. The owner is probably having a rough time right now. Find a chance to speak privately and see if you can help. Maybe you have capital, expertise, or other resources the business owner can use. Just offer whatever help you can, on whatever terms make sense for you. Small business owners have their hands full even in normal times. Right now, they need all the help they can get. And we will all win by helping them pull through. Our local Puerto Rico government and my own homeowners association have been very cautious about COVID-19. But on a small island where people are typically clustered together in communities of all sizes, and the culture is to socialize a great deal, cautious is not a bad thing. Masks are the norm in business situations. Which brings me to one of my great frustrations: the maddening politicization of this situation. I get that we can politely and aggressively debate taxes or regulations or any number of issues. But the practice on both left and right of cherry-picking data to score points on your political opposition about a virus that is affecting us all so deeply just seems beyond the pale to me. A plague on all their houses, if I can use that pun without being too politically incorrect. On a positive note, I am following credible research from highly respected scientists right now which has the potential to be a true game changer, dramatically shortening recovery time. Hopefully, I will be able to tell you more in about a month. I hope it’s good news. So far, it seems to be. And with that, let me hit the send button and wish you a good week. Stay safe out there! Your looking for that Hail Mary pass analyst,   | John Mauldin

Co-Founder, Mauldin Economics |

P.S. Want even more great analysis from my worldwide network? With Over My Shoulder you'll see some of the exclusive economic research that goes into my letters. Click here to learn more.    | | Share Your Thoughts on This Article | | |

|