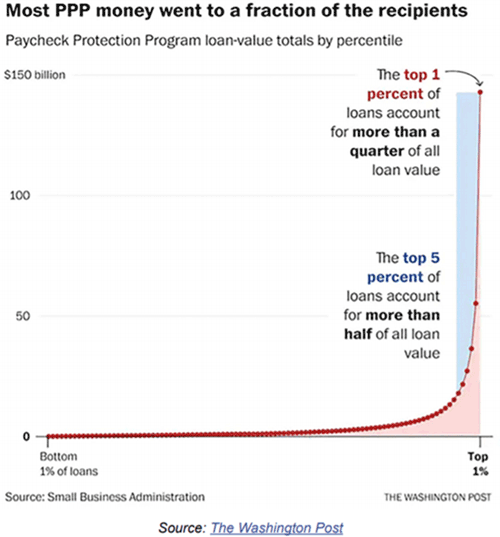

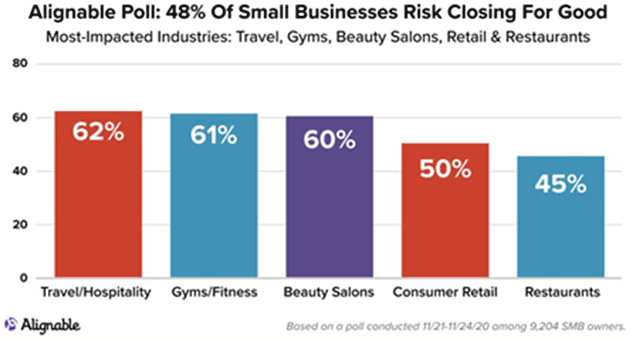

Survival of the Biggest By John Mauldin | Dec 12, 2020     The essential point to grasp is that in dealing with capitalism we are dealing with an evolutionary process… At the heart of capitalism is creative destruction. …Situations emerge in the process of creative destruction in which many firms may have to perish that nevertheless would be able to live on vigorously and usefully if they could weather a particular storm. —Joseph A. Schumpeter The most important feature of an information economy, in which information is defined as surprise, is the overthrow, not the attainment, of equilibrium. The science that we have come to know as information theory establishes the supremacy of the entrepreneur because it appreciates the powerful connection between destruction and what Schumpeter described as "creative destruction," between chaos and creativity. —George Gilder In its purest form, capitalism is an evolutionary process. Businesses that best adapt to changing conditions survive and grow. Typically, that means offering a product or service superior to current ones, or giving consumers more choices. Weaker or poorly managed businesses that don’t adapt to the new situation wither and eventually die. That’s not always pleasant but it’s how nature works. Joseph Schumpeter coined the term “creative destruction” to describe the process. It is not pleasant when you are on the destruction end, but the creative side can bring innumerable joys and sometimes even wealth. The difference, however, is we don’t have capitalism in its purest form, or anywhere close. It has been tweaked, modified, corrupted and/or regulated into something else, the particulars of which vary. The common thread is that survival depends not only on impersonal nature, but on other non-random forces that can be manipulated. Governments can and often do create barriers to entry, protecting favored constituencies and groups from competition. Now we are in an odd situation where something from nature is generating an unnaturally negative economic outcome. The virus—or specifically the political response to it—is causing a mass extinction event for small businesses in certain sectors. At the same time, some large businesses are reaping a bonanza of revenue from the same pandemic. This isn’t happening randomly, nor is talent (or lack thereof) determining who wins. One of the main factors is something else: size. In the most-affected sectors, the largest players are winning and the smallest ones dying. Instead of survival of the fittest, we see survival of the biggest. The problem: Biggest isn’t always best. You already know the bad news: This pandemic is slaughtering small businesses. Not all small businesses, mind you. Some are fine. This pandemic seems laser-focused on those involving personal contact, the ones whose owners and employees actually see us in person, smile at us, and sometimes even touch us: restaurants, bars, hotels, hair salons, gyms, spas, shops. Many types of healthcare. The list goes on and on. Those are the prime victims, economically speaking. And often medically, too, since that same personal contact puts the owners and workers at higher infection risk. I want to partially repeat one of the quotes from Schumpeter above (emphasis mine): …Situations emerge in the process of creative destruction in which many firms may have to perish that nevertheless would be able to live on vigorously and usefully if they could weather a particular storm. The COVID-19 storm has been particularly brutal to many. Initially, the US made at least some attempt at a reasonable policy response. The Paycheck Protection Program was supposed to help small businesses continue paying people for eight weeks and also cover some fixed expenses. In practice, doing that proved a lot more complicated than expected. Hundreds of thousands, maybe millions of small businesses got nothing. Some who did get benefits found the rules prevented them from using the money in the ways they needed. And then even that money ran out. And not surprisingly, larger companies benefited more in terms of dollars received than truly small businesses. The chart below looks like a confirmation of Pareto’s principle, the famous 80-20 rule: Almost all the money went to a small fraction of the companies.  There’s more, too. Small businesses have been disproportionately harmed by haphazard, inconsistent local orders restricting how they operate or sometimes closing them completely. I get the health concerns. The initial closures last spring made sense, given how great the threat looked and how little we knew at the time. We have since learned a lot. Governors and mayors can be more precise and, very important, help small businesses operate safely. Instead, they have often produced the worst of both worlds, harming businesses and workers and still not slowing the virus. But here again, the federal response (or lack thereof) is part of the problem. Local authorities are in near-impossible positions. Closing businesses, even when it’s the right move, reduces their own tax revenue and creates expensive community turmoil. But they fear opening everything normally would intensify the pandemic. So they flail around, learning by trial and error. It is a messy and ugly process even if everyone is sincerely cooperative and willing to sacrifice, which is not the case. It would be going a lot better if Washington offered clearer guidance and financial help. However you assign blame, and there’s plenty of it, the results are the same. Small businesses aren’t just wounded. Many are dying. Here’s a recent survey of owners, almost half of whom say they are in imminent danger of permanent closure.

Source: Forbes I know better than most the risk of opening a small business, having been a serial entrepreneur, sometimes successfully and sometimes not. Startup risk is high in the best of times. If these owners had made poor decisions or failed to deliver what customers want, then their demise would be sad but necessary. It would be “creative destruction” at work, the invisible hand telling owners to do something else. But that’s not what happened. This pandemic is more like a natural disaster. Actually, it’s worse. If you own a beachfront bar, you know to expect hurricanes. You can design your business and insure yourself for the possible harm. Earthquakes shouldn’t surprise you if you build your factory on the San Andreas Fault. These are known risks. You can calculate whether they are worth taking, and maybe build your factory somewhere else. But there was no way to anticipate this scenario. The insurance industry regards pandemics as literally uninsurable. We talk, rightly, about “protecting the vulnerable” from COVID-19. That is the government’s proper role and should be everyone’s goal. We do it (or at least try) even for the elderly who may die soon anyway, because protecting life is in everyone’s interest. Similarly, we should protect the most vulnerable businesses from the pandemic. Maybe they wouldn’t have made it anyway, but the economy will sort that out. They deserve a fair chance. Sadly, the opposite is happening. My friend Neil Howe, of Fourth Turning fame, recently referred to a New York Times op-ed by Austan Goolsbee. You may recall Goolsbee as a White House economic advisor in the Obama years. Needless to say, we disagree on some policy questions but he was on target in this column, titled “Big Companies Are Starting to Swallow the World.” Goolsbee describes how the pandemic created a troubling split in the economy. Many large companies are seeing strong growth while small businesses, as described above, struggle to survive. He thinks this explains some of this year’s stock rally. The market seems to believe public companies will benefit from rising demand while facing less competition from small businesses. I fear he is correct. He notes it isn’t new to see large companies buy smaller competitors, or otherwise try to stifle competition, but he thinks this time is different. And he thinks he knows why. What is unusual at this moment is the extreme divergence in the health of different types of companies: Many of the biggest are flush with money, while smaller competitors have never been in more precarious shape. The Federal Reserve’s Flow of Funds latest data (from the first quarter of 2020) shows that at the outset of the pandemic, nonfinancial businesses were sitting on an eye-popping $4.1 trillion of cash—the largest hoard ever. These companies also received huge tax reductions in the Tax Cut and Jobs Act of 2017, including incentives to acquire other firms. Then, earlier this year, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (or CARES) Act, aimed at rescuing the economy from the ravages of the coronavirus, empowered the Federal Reserve to provide up to $5 trillion in subsidized loans for large businesses. Given such enormous resources, many corporate giants are in great shape, but the rescue money for firms without access to public capital markets ran out at the end of July, and the prospects for many small businesses are bleak. In his own comments, Neil Howe adds this: To explain the extraordinary gains of large businesses over small in 2020, we need to point out the unique advantages that the pandemic has conferred to the scalable and impersonal giants—most obviously, in digital tech and communications, but also in pharma, consumer credit, discount retail, and fast-food chains. This stands in contrast to everything small, local, informal, and personal—which has gotten hammered. Yet we also need to acknowledge how the response to the pandemic has practically guaranteed that the big would get still bigger, by providing market support and near-bottomless liquidity to the giants who already possessed the most cash-in-hand… [JM—and I would add access to cheap loans.] … [E]ver-larger scale inevitably creates monopoly pricing power for the incumbent giants and suppresses start-ups, job churn, mobility, and innovation among the smaller players. In time, he [Goolsbee] suggests, this cycle can become self-perpetuating. In product markets, monopoly rents enable the bigger players to underprice or buy out (in "killer acquisitions") smaller competitors. In financial markets, the herding of passive investors into massive ETFs furnishes the giants with the lowest cost of capital and leveraging. And in politics, the bigger players can make sure the rules favor them and that antitrust enforcement remains ponderous and underfunded. Goolsbee points out that, while merger activity has roughly doubled over the past decade, federal spending on antitrust enforcement (through the Justice Department and the FTC) has fallen sharply along with the number of enforcement actions. Now, some of this actually is market-driven. Scale matters. Large restaurant chains can buy their meat and produce in quantities that let them demand rock-bottom prices. This gives them an advantage over small local owners. The same for many other businesses. Amazon can offer fast, free shipping on many products because it gets lower rates and has a vast warehouse network. Sometimes big companies can more efficiently provide what consumers want. That’s just life. This time, however, the big companies have those advantages and the benefit of low-cost Federal Reserve financing and less competition because so many smaller companies are struggling or out of business. That is not natural. It is what Neil Howe calls “monopoly rents” and it wouldn’t happen if not for government and central bank interventions. This is a problem not just for small businesses, but for everyone. Large organizations do certain things very well. Quick innovation typically isn’t one of them (although there are some clear exceptions). Bigness breeds caution and discourages the kind of risk-taking that leads to breakthroughs, although without them, the economy becomes sclerotic and growth slows. We’ve seen this over the last decade; we don’t need it to get worse. (Technology is the exception that proves the rule.) Moreover, small businesses are the academy of entrepreneurship. People start businesses and learn the ropes. Even if they fail, they frequently go on to contribute in other ways. We need more small businesses, not fewer of them. Every life lost in this pandemic is tragic. In a different way, every lost business is tragic, too. Their absence leaves a gap in the economy and in our lives. | | Only Until Dec. 21

You Are Invited to Join Our

Most Exclusive Service Become an Alpha Society member today and enjoy unlimited access to all our subscription services—for as long as we publish them! 3 valuable bonuses are yours for joining today...

find out more here. | |

|

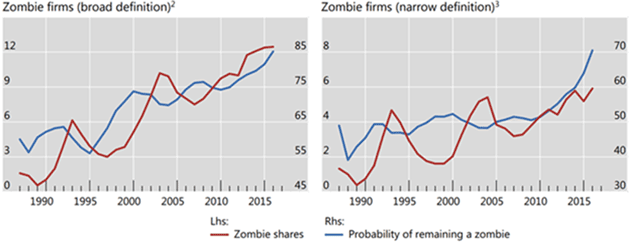

My friend Niels Jensen at Absolute Return Partners has a new letter entitled “The Zombies Are Coming,” by which he means not actual zombies (though that would be on par for 2020) but zombie companies. He defines them this way. A zombie company is simply a company that is neither dead or alive. In other words, it is in so much debt that any cash generated is being used to pay off the interest on the debt […]. This means that there is no spare cash or capacity for the company to invest or grow. This means that it is unable to employ more staff but on the flip side, as long as the company is not actually losing money on an operational basis, it does not need to make further redundancies either. Then he goes on to begin to cite studies from the BIS and OECD from 2017 and 2018. It has gotten worse. Quite interestingly, BIS found that, from virtually non-existent as recently as 30 years ago, by 2016, more than 12% of all listed, non-financial firms in the world had been zombified (Exhibit 2). At the same time they found that, whilst the prevalence of zombie firms is on the rise, so is the probability of them staying (barely) alive for longer.

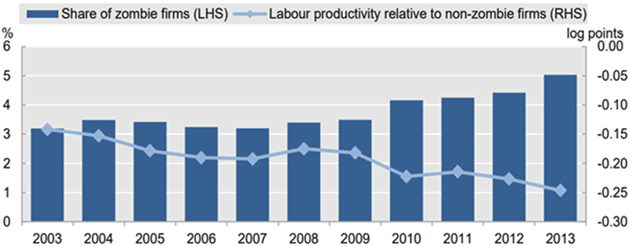

Source: ARP Cheap loans for large companies aggravate this “zombification” problem, disrupting the creative destruction which brings prosperity and jobs. Niels also demonstrates a link between cheap loans and bank health. The more companies that banks lend to that are on debt life-support, the harder it is for them to call the loan and take a hit to their own capital. Why is all this important? Because it stunts economic growth. Let’s begin with the zombie share’s impact on productivity. In a paper from 2017, researchers from OECD documented a link between the share of zombie firms and labor productivity when measured relative to labor productivity in non-zombie firms (Exhibit 4). OECD defined a zombie firm precisely the same way BIS defined a broad zombie some 18 month later, so the two studies are comparable in that respect.

Exhibit 4: The share of zombie firms vs. labour productivity (average across 8 OECD countries)

Source: “The walking dead? Zombie firms and productivity performance in OECD countries”, Economics Department Working Paper no. 1372, January 2017 When workers go from a zombie company to a productive company their own labor productivity increases, benefiting the total economy. Keeping large companies on life support is one reason that economies are growing slower than in the past. Leuthold Group calculates 15% of large US companies are in some form of Zombification.

Exhibit 7: Percentage of zombies in Leuthold 3000 universe

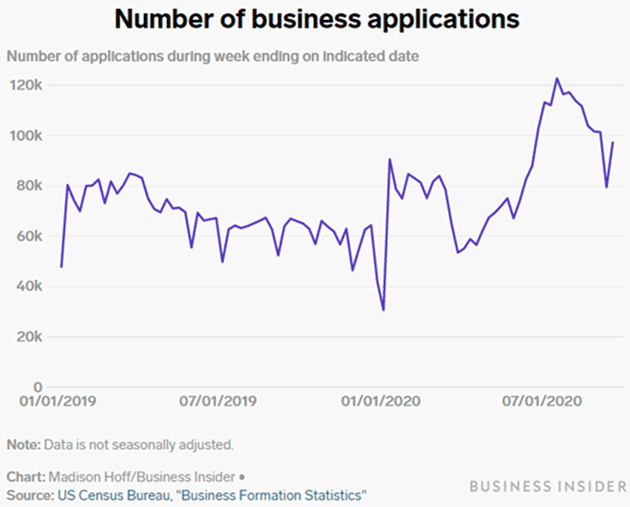

Source: Financial Times How long can those zombies hold on? From Friday’s WSJ: Economic indicators are pointing to a second wave of bankruptcy for businesses of all sizes as well as households, likely to hit in the second half of next year, according to Ed Altman, the finance professor and bankruptcy guru, WSJ Pro Bankruptcy reported. A number of signs suggest a coming surge in defaults for nonfinancial companies, which picked up with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic but have been somewhat muted thanks to unprecedented support for financial markets from the Federal Reserve. Chief among the indicators pointing to another bankruptcy wave ahead is the ratio of nonfinancial corporate debt to gross domestic product, which spiked to an all-time high of close to 57 percent in the first half of 2020, Altman said. But it’s not all bad. Good things are happening in the background… Well over 100,000 small businesses failed this year and we could lose many more. But I continue to believe those entrepreneurs have something in their DNA that will get them back on the playing field. We now have data that demonstrates it, too.

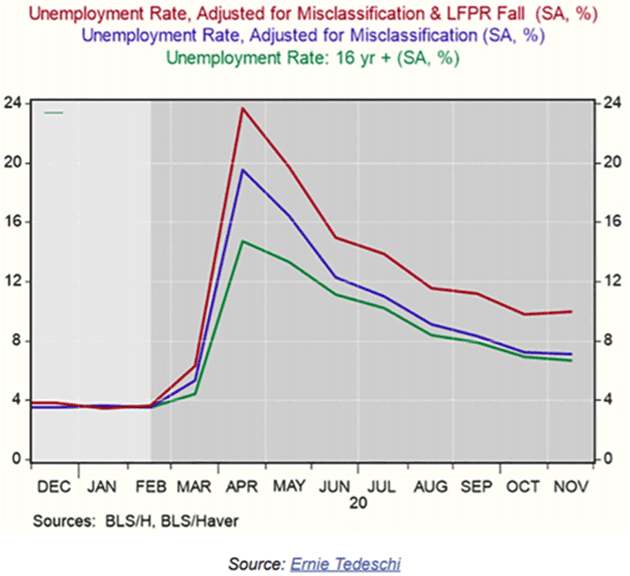

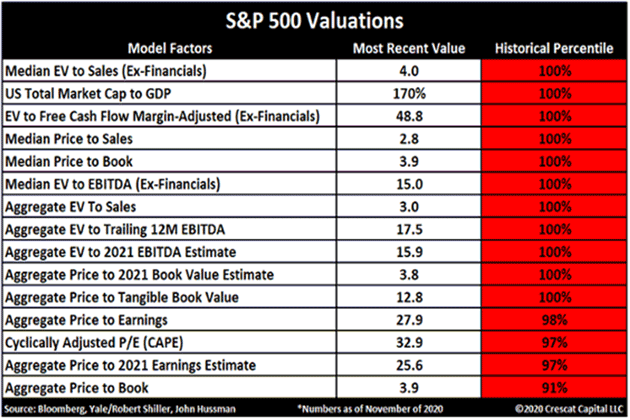

Source: Business Insider Clearly, a significant group of entrepreneurs has decided that now is the time to start out on their own (perhaps again). If you are looking for green shoots, there is no clearer example. So where do we go from here? Obviously, a great deal depends on how fast the vaccines roll out. The most optimistic view suggests sometime this summer for “herd immunity.” More realistic analysis says late 2021 for the developed world. We should note, though, the innovation is still underway. I am personally following a vaccine candidate that should be out this summer with a novel platform, with likely very few side effects, no need for refrigeration and other positives. I bet we see more like that. Although the Labor Department suggests unemployment is 6.7%, we have also seen massive dropouts from the labor force. Adjusted for that, unemployment would be roughly 10%:  The US and the rest of the developed world will begin to recover, especially after widespread vaccinations. But it is going to be a lot slower than most people think. Coming back from 10% unemployment is difficult. Buying patterns, personal habits, how we conduct both our personal lives and our businesses, much has changed. Consumers and businesses of all sizes have to adjust. For some businesses, it is going to be very difficult and for others will be like riding a rocket ship. Mauldin Economics is a small business like many others. We are thankfully getting through this trial better than most, so we try to help however we can. Recently we offered a no-obligation “open house” weekend for some of our most popular research services. I know many of you took advantage. We hope you found it useful. Soon we’ll have another opportunity that might help you. Our Alpha Society exclusive membership service will be taking a limited number of new members until December 21. It gives you lifetime access to all our premium services for as long as we publish them, at a dramatically lower price than subscribing annually. Members get some other special benefits, too. You can find all the details here. Here in Puerto Rico we have new pandemic restrictions. For some reason, the governor thinks that selling alcohol on the weekends will contribute to coronavirus spread. Restaurants are limited to 30% capacity. Sundays are total lockdown for everything. Beaches except for exercise, and never in groups, are off limits. That being said, there is so much opportunity everywhere I look in Puerto Rico. Then again, that would probably be the case in much of the world. I just see opportunities… I haven’t mentioned much about the stock market and valuations lately, though I intend to write about my view of the markets soon. For now, I will just share this table from my friend Doug Kass, which I pretty much think says all we need to know about valuations:

Source: Doug Kass More on valuations and such things later, but for now let me hit the send button and wish you a great week! Your ready for 2021 to get here analyst,   | John Mauldin

Co-Founder, Mauldin Economics |

P.S. Want even more great analysis from my worldwide network? With Over My Shoulder you'll see some of the exclusive economic research that goes into my letters. Click here to learn more.    | | Share Your Thoughts on This Article | | |

|