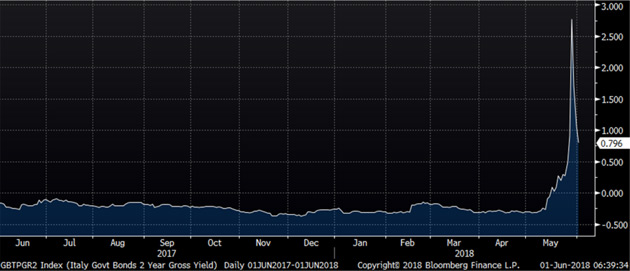

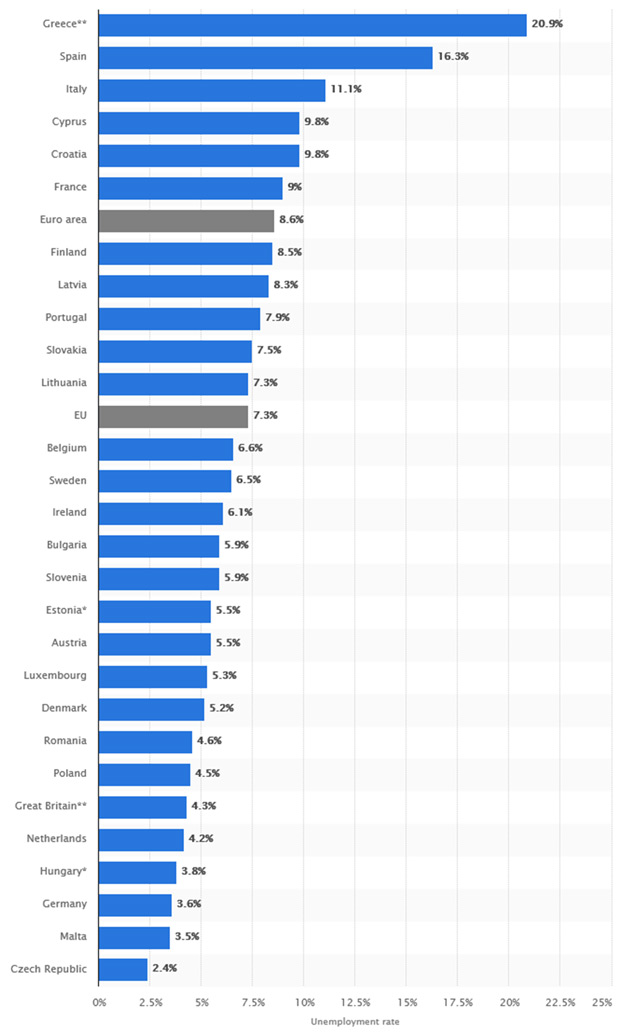

The Italian Trigger By John Mauldin | Jun 01, 2018 Train wrecks and their financial analogues are a worldwide phenomenon. Europe, as I have written for several years, remains a giant accident waiting to happen—as Italy reminded us last week. You may have noticed the results when US trading resumed Tuesday. A wider crash may not be imminent but is certainly possible and will have worldwide effects if/when it happens. So now is a good time to review what’s already happened and what could be coming. This letter is chapter 4 in my Train Crash series. If you’re just joining us, here are links to help you catch up. Briefly, my thesis is that over the next decade, we will endure increasingly damaging debt crises that culminate in a coordinated global default—“The Great Reset,” as I call it. There are limits in how much leverage the world can handle, and I think we are already beyond them. And that is before we have a global recession. The only question now is how we will manage the collapse. I previously quoted former BIS Chief Economist William White on how this will all unfold. Here’s his key point again. … the trigger for a crisis could be anything if the system as a whole is unstable. Moreover, the size of the trigger event need not bear any relation to the systemic outcome. The lesson is that policymakers should be focused less on identifying potential triggers than on identifying signs of potential instability. Bill says the financial system is so fragile that practically anything could trigger a crisis. Better to watch for signs of potential instability… and in Italy, instability isn’t just a potential. It is a probability at some point. Italy had been without a government since its March 4 election, which yielded a hung parliament with no party or coalition holding a majority. The Five Star Movement and Lega Nord finally reached a deal, to most everyone’s surprise since those two parties, while both broadly populist, have some big differences. Nonetheless, they found enough common ground to propose a cabinet to President Sergio Mattarella. Italian presidents are generally seen as rubberstamp figureheads. They really aren’t supposed to insert themselves into the process. Yet Mattarella unexpectedly rejected the coalition’s proposed finance minister, 81-year-old economist Paolo Savona, on the grounds Savona had previously opposed Italy’s eurozone membership. This enraged Five Star and Lega Nord, who then ended their plans to form a government and threatened to impeach Mattarella. Such acrimony isn’t new in Italy. Politics there are messy, to say the least. Savona’s possible appointment set off alarm bells because it suggested the new government might try to take Italy out of the eurozone. Neither coalition party had raised that possibility in the campaign. The main promises were to reduce taxes and introduce a kind of universal income for poor and unemployed Italians. In fact, the polls clearly demonstrate that Italians still want to stay in the eurozone. Not as much as the Germans or the French, but a clear majority. At the beginning of the euro experiment back in 1999, 81% of Italians supported the euro and now only 59% do. (Some polls show as much as 66%.) Whatever the number, we can see a trend there. On the flipside, only a small majority of Germans supported the euro at the beginning and now 80% do. France has seen a smaller rise in support, from 67% to 71%. And that pretty much tells you everything you need to know about which countries the euro helped. And in a few paragraphs, we will let those numbers instruct us as to the future direction of Europe. The slowly disintegrating numbers in favor of the euro and Italy reflect the fact that the Germans and French are better off than the Italians compared to 17 years earlier. Germany, joined by the Dutch, Finns, and Austrians, runs a monster $1 trillion plus trade surplus with the rest of Europe and the eurozone. And that makes the workers in primarily Mediterranean countries increasingly less productive than the northern countries, which ultimately forces their wages down. So, the northern Italian business populist party (Lega Nord) feels Italian businesses are losing out because of the euro, and the southern Italian populist party (Five-Star), representing an area where wages are suppressed and unemployment high, have serious concerns about the euro. My friend Louis Gave noted that Mattarella’s decision was “not a crime, it was worse—it was a mistake.” Even Mattarella has now acknowledged that. In a face-saving measure, the two populist political parties suggested a new finance minister, Giovanni Tria, who has some (let’s just say) interesting economic points of view, but at least he is in favor of the euro and thus allows Mattarella to correct his mistake. But then he approved Savona, whom just days earlier he had rejected as a potential finance minister due to past anti-euro views, to be the new Minister of European Affairs. If you are confused, remember this is Italy. Everything is confusing there, except the food. Italy is not Europe’s only problem. The big Kahuna is Germany, which spent years offering generous vendor financing to the rest of the continent to entice the purchase of German goods. The result: a giant trade surplus for Germany and giant, unpayable debts for those who bought German goods. Greece, for instance. But a lot of that debt is on the balance sheet of European banks. S&P just cut its rating for Deutsche Bank to BBB+. That is only a few notches above junk status. And if there were Italian issues? A lot of German banks could see their ratings fall to below junk. Ugh. Will Germany let Deutsche Bank fail? Simple answer, no. But they may not feel the same love for Deutsche Bank shareholders. Spain is not quite the basket case that Italy is, but its banks are certainly wobbly. Spanish lawmakers this week gave a no-confidence vote to Prime Minister Rajoy’s conservative government and installed a socialist prime minister. The Spanish economy is actually much improved; other issues are creating political instability. The UK is still winding its way down the Brexit path, which doesn’t directly affect the euro but is disruptive nonetheless. All in all, Europe is mostly stable but has problem spots like Italy. All it takes is one of them to bring the whole structure down. That’s why we see market moves like Italian two-year bond yields zooming from below zero to almost 3% within days and then falling below 0.8% the next few days. That’s some serious volatility. (h/t to Peter Boockvar for the chart.)  That’s not normal and doesn’t happen in a monetary union in which all the members share the same goals. And that’s kind of the problem: European governments have irreconcilable interests and thus don’t trust each other. By accident of history and geography, the continent is fractured into dozens of competing economies, languages, and cultures. Unity has long been a dream, but only a dream. Simply avoiding war is hard enough. The Euro currency union is fatally flawed because it leaves each member state to set its own fiscal policy. There are good reasons for that, but it is not sustainable indefinitely. The Eurozone must get either much more centralized or fall apart. All the Rube Goldberg contraptions the ECB and others invent are temporary fixes. They’ve worked so far. They won’t work forever. And that brings us to the latest strange proposal. Italy’s situation could blow up the fragile trust that keeps Europe together, and the leading parties may even be planning for it. The discussions between Lega Nord and Five Star included an idea called the “mini-BOT” that would effectively serve as a parallel currency. The BOT is Italy’s Treasury bill, and as in the US, it serves as a kind of cash equivalent in electronic trading. The mini-BOT would be a government debt instrument, in paper form, that pays zero interest and never matures. The government would use it to pay social benefits and accept it for tax payments. Private businesses would not be required to accept it, but they could. Private businesses and individuals would also, in theory, buy the mini-BOT as a way to pay their taxes. But they would buy them at a discount. So, traders would immediately set up an arbitrage where the person getting the social benefits payment could sell them for euros for, call it, a 5% or 10% haircut. Former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi, who is still a force in Italy, insists this would be legal. The Northern League sees a way to ease the transition out of the euro and the Five-Star Movement sees a way to increase spending without having to take on euro debt. And since the new coalition government wants to increase the deficit an additional $180 billion euros or so through a combination of tax cuts and increased spending, this is being seriously proposed. The mini-BOT probably could be a practical alternative to the euro for many transactions. From what I’ve read, the other eurozone countries would have difficulty stopping it because the euro would still be the only formal “currency.” And other Mediterranean countries would watch this experiment and begin moving in the same direction themselves. You see where this goes. Italy might be able to use mini-BOTs (or let’s be honest and call them the new lira) to finance deficit spending without breaking eurozone rules. This could ultimately debase the euro and blow apart the eurozone. Germany would have to leave. From there, you can draw your own map. Is this what the Italian populists want? Some of them, yes, but I suspect their leaders know not to go too far. More likely, they see it as a bargaining chip—a plausible threat they can use to extract concessions from the ECB and other eurozone leaders. The Greeks threatened something similar in 2015 and it didn’t work. I think Italy has a stronger hand. But it gets scarier when you think about how this could happen. If Italy’s new government decides to launch a parallel currency, they will probably do it with no warning at all. Tipping their hand would spark capital flight and reduce the benefits. We could literally wake up one morning to learn the lira (or something like it) is back and Germany is leaving the Eurozone. Imagine how markets would react. I think this scenario is unlikely, but it points to something else. As the coming debt crisis matures, national leaders and central bankers will find their choices narrowing. I’m constantly amazed at their creativity, but it has limits. They can’t kick the can down the road forever. At some point, the road ends and then they have to choose. When your only choices are “impossible” and “terrible,” then you pick the latter. We are going to see previously unthinkable ideas be seriously considered, and sometimes chosen, because all other options are even worse. Here’s the problem that’s brewing. Germany and the other northern countries, but especially Germany, have prospered tremendously under the euro regime. If the eurozone were to break up, German GDP would simply fall out of bed. Half its economy is comprised of exports. Further, the new German currency would get stronger which would even put more pressure on German exports. The Italians have no solution for their debt. Greece has been in a seven-year depression. And while some of the other countries are improving, unemployment rates in most of Europe are still lackluster to say the least. See the chart below and notice the high unemployment rates. And understand that the unemployment rates for young people (millennials) are probably double that. One in three Italian youth are unemployed.

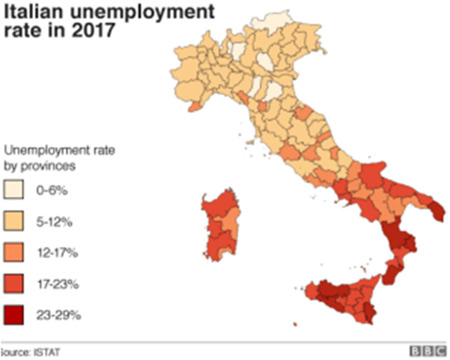

Source: Statista Let’s drill down on Italy’s employment data. Notice the further south you get, the higher the unemployment rate goes. That’s the Five-Star Movement’s base. The other part of the new majority is now called the League (formerly the Northern League) and is powerful in the low unemployment manufacturing regions of northern Italy. And for all the Italian problems we’re talking about, Italian manufacturing is a powerhouse. (Map h/t to Dennis Gartman.)  This is why you can’t entirely dismiss the notion of a parallel currency in Italy. The southern portion of the country wants to see more spending and the northern portion would like to ease out of the euro. Politics makes extraordinarily strange bedfellows in Italy. It’s not quite as outlandish as President Trump and Bernie Sanders forming a coalition government, but it was unthinkable just a year ago. Germany and the rest of the export driven countries need to stay in the euro in order for their economies to grow and prosper. The southern countries need to figure out how to deal with their debt. Italy is around 135% of debt-to-GDP today. I still think the most probable scenario is that Germany and the Netherlands reluctantly agree to let the European Central Bank mutualize all the sovereign debt, taking onto their balance sheet and issuing new ECB-backed debt for the entire zone. There would have to be serious constraints on running deficits after that point, but it would prevent a breakup, or at least delay it for another decade or so. Kind of the ultimate kicking the can down the road. None of these dire possibilities appear to be in play right now. One way or another, Italy will slide through this. It could drag on a few months. But Tuesday’s market spasm ought to be a warning sign. Traders still know how to hit the “sell” button and will do it quickly if something surprises them. This time, it was manageable. At some point, it won’t be. My friend Doug Kass, a brave soul who has been trading longer than most, actually turned bullish on banks following this week’s selloff, shedding his short positions. After Doug wrote that, the Federal Reserve Board voted to loosen the Volcker Rule that had limited proprietary trading. Other agencies must agree, so it’s not a done deal yet. In theory, this should help banks and may also restore some of the bond market’s lost liquidity. I don’t think it will solve all our problems or prevent the larger crisis that I think is coming. Charles Gave, who was also trading before today’s wizards were born, is questioning some of his assumptions. His longtime models say the time is nearing to sell US stocks and buy German stocks. But that model makes assumptions that are no longer true. For one, it assumes capital will flow to the place where it can be used most efficiently, and exchange rates will stay suitably flexible. Neither is necessarily true in an era of collapsing alliances and rising trade barriers. Speaking of trade, with Trump once again getting ready to impose steel tariffs on the EU and lumber tariffs on Canada, things can get even more volatile. Since lumber is basically 20% of the cost of a house, a 20% increase in lumber prices (a gift to US lumber companies) would raise housing construction cost by 4%. Cars and aluminum cans would rise in costs. Not only are the countries that are paying the tariff being taxed, US consumers will be taxed with higher prices. This is not exactly the best way to stimulate an economy. Worse, it could all change again as negotiations continue, and businesses need policy certainty. I haven’t written yet about the housing markets in Canada and Australia, both of which are in worse shape than the US was ten years ago. Especially Australia. You can just go around the world and find Bill White’s “pockets of instability” everywhere. One or two here and there is not an issue. The world typically just shrugs it off. But we are now beginning to see problems in a much larger geographical space. Argentina? Mexico electing a radical socialist? Where does it end? I want to thank everyone who subscribed to our rejuvenated Over My Shoulder service. As I explained, it helps me keep Thoughts from the Frontline regular and free. But more important, you’re getting tons of valuable information to help you navigate through this economic minefield. In the last month alone, Over My Shoulder subscribers received valuable research and analysis from Peter Boockvar, Steve Blumenthal, Woody Brock, Jesse Felder, Charles Gave, Louis Gave, Lacy Hunt, Doug Kass, David Kotok, and Grant Williams. Buying it separately would have cost thousands of dollars, but you got to see it for only $9.95. That counts as one of the world’s greatest bargains. Better yet, you get the benefit of all that research without even having to read it. My co-editor Patrick Watson or I prepare brief summaries of each report that tell you the key points and bottom line. You can stop there or, if you have time, go on to read the full story. It’s your choice. If you enjoy my letters and haven’t tried Over My Shoulder, you are missing out. Click here to learn more and give it a try. I am trying not to schedule yet another plane trip until August, but I know a few quick trips will probably intrude on my summer schedule. I will let you know if maybe I’ll be in a town near you. You have a great week and here’s hoping the market rally continues. Lastly, three cheers for the jobs report. Even with all the world’s instability, the US economy keeps churning along. We have a more volatile trading environment, but nothing to signal a recession in 2018. So, let’s enjoy the summer. Your running as fast as his puppy-dog legs can take him analyst,   | John Mauldin

Chairman, Mauldin Economics |

Share Your Thoughts on This Article |