The Trump Trade War Recession? By John Mauldin | Sep 29, 2018 “A conservative is someone who stands athwart history, yelling stop, at a time when no one is inclined to do so, or to have much patience with those who so urge it.” —William F. Buckley, Jr., 1955 I will never compare myself to Bill Buckley, as a writer or anything else. He was one-of-a-kind and a personal hero who I am disappointed to say I never met but who I read a lot. The response to my recent tariff comments gives me a small hint of how it must have felt to “stand athwart history” and launch the modern conservative movement. Many of you support the tariffs. And I understand your reasons. I really do. Free trade used to be a core belief of the conservative movement. Hayek, Friedman, Mises, Rothbard, and numerous other economists eloquently explained why. Several liberal economists agree. Conservative politicians spent the last few decades moving us in that direction, albeit imperfectly and with some big mistakes along the way. But few disagreed with the ideal. Let me be clear on this: I do not think the tariffs on China are going to cause a recession. But if we have a recession, that is precisely what the Democrats will say. Democrats will not run against the Fed, investor sentiment, markets, Italy, or anything else that actually causes the next recession. They will be running against Trump and everything will be his fault. It will be the Trump Trade War Recession. Whether or not it is true is immaterial. That is neither here or there because a trade war with China introduces too many variables into an already difficult situation. Let’s look at what is actually happening on the ground. We all wonder if Trump’s trade actions are as random as they appear or if there is a broader strategy. Some of my contacts argue that the relatively strong US economy allows the administration to take a harder line than would normally be advisable. We can ride out a trade war better than China can, the thinking goes. This only works if the US economy keeps prospering long enough for the tariffs to make China bend. We can postpone a recession for another year or two if the trade war doesn’t intensify and Europe holds together. Since it is intensifying—with a new round of 10% tariffs taking effect this week and more to come in January—we may not get that time. In other words, tariffs could end the conditions that justified them. Something similar happened before, during the most famous trade mistake in US and global history: the 1930s Smoot-Hawley tariffs. Similar to today, the Roaring 1920s saw rapid technological change, specifically automobiles and electricity. This created a farm surplus as fewer horses consumed less feed. Prices fell and farmers complained of foreign competition. Herbert Hoover promised higher tariffs in his 1928 presidential campaign. He won, and the House passed a tariff bill in May 1929. The Senate was still debating its version of the bill when the stock market crashed in October 1929. Today, we use that event to mark the Great Depression’s beginning, but at the time, people didn’t know they were in a depression or even a recession. Most economists expected a quick recovery. Stocks did recover quite a bit in the following months, though not back to their prior highs. So, when the Senate finally passed a tariff bill in March 1930, the thinking was not that different than we see today. They thought they could preserve and even extend the good times. But conditions worsened quickly and by 1931, unemployed men were standing in soup lines.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons In 1932, both Smoot and Hawley lost their seats as Franklin Roosevelt beat Hoover in a landslide—57% of the popular vote. That history won’t necessarily repeat this time, but it’s surely not a good omen. John Nash (one of the world’s great mathematicians, Nobel laureate, and centerpiece of the brilliant movie A Beautiful Mind) developed multiplayer game theory. Essentially, an equilibrium develops around the rules as they are at the moment. If somebody changes the rules, no matter how rational the rule change may seem to be to the person who’s making the change, it makes everybody else change their response. Trump’s actions, especially in regard to China, may be perfectly rational. China is not playing fairly. But his actions change the rules and everybody else is forced to react. Throw in NAFTA, Europe, and all the other trade negotiations, and things get complicated. Yes, we have a new trade deal with Korea. The US is marginally better off. Trump is trying to do a one-off trade deal with Japan. Abe is cautious because Trump wants to open up Japan’s markets to US agriculture. We pulled out of the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP) because it had flaws—clearly. But it served the purpose of isolating China. Trying to do bilateral trade agreements with every one of those partners is going to be extraordinarily difficult and time-consuming, if not impossible. And so, everybody reacts to try to change the circumstances to their own benefit. This is multiplayer game theory on a scale so vast that it is almost impossible for a human being sitting in the middle of the United States working at his job, just trying to get through the day, to understand. And so, they get angry and say we need more tariffs to protect America. Just like every other voter in every other country is trying to figure out how to protect their markets. Something else I keep hearing is variations of, “China is cheating, and we have to do something.” This comment from reader Justin McCarthy is typical. I get all the handwringing and pearl clutching about trade wars. But it really appears that true free and fair trade is an illusion. China cheats. Why? Because it can. Everyone pretty much acknowledges it. But where are the projections and analyses of the long-term consequences of permitting the status quo to continue? What are the consequences of letting the balance of power shift in China's favor? I see a lot of angst about trade wars but no discussion about the effects of no action. Justin said this nicely, but I have to disagree. He’s right that “true free and fair trade” is not what we have, nor have ever had. But trade isn’t a binary condition. Today, we see near-total isolation on one extreme (think North Korea) or at the other end extensive trade freedom, as nominally exists within the European Union. There’s lots of room in between. China cheats in many and various ways, which I have stated are problematic. I’m not happy with the status quo, and I want to change it. The question is, are tariffs the best way to accomplish this? A second question is, even if tariffs accomplish the goal, will there be side effects that reduce or eliminate the benefits? I see a lot of unintended consequences. A few weeks ago, I described how a sandpile can slowly grow in size, apparently stable, but in reality, it has many hidden fingers of instability. At any moment, something could trigger an avalanche. The global trade system is something like that. Of course, it’s not perfect or even optimal. Countries erect barriers to their advantage. I can point to several countries whose economic policies are mercantilist, but at least everyone knows about them. We see the fingers of instability and leave them alone, lest we trigger an avalanche whose victims are impossible to predict. It is a kind of equilibrium. Everyone’s incentive is to avoid catastrophe and make incremental improvements. That makes trade talks extraordinarily difficult. The Trump administration doesn’t seem to care about equilibrium. Whether the president himself or those around him, the strategy appears to be “kick apart the sandpile and make everybody rebuild it.” And whether we like it or not, many of Trump supporters actually like the concept of throwing a wrench into the system. So, it is not the case that the US has no choices. We have many choices. Tariffs are the wrong one. But then, that is just me and I am one lone voice and vote. Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross is a brilliant businessman. He is proving less than effective as a public advocate for administration policy. Earlier this month, he appeared on CNBC to tell us the latest tariffs won’t be so bad.

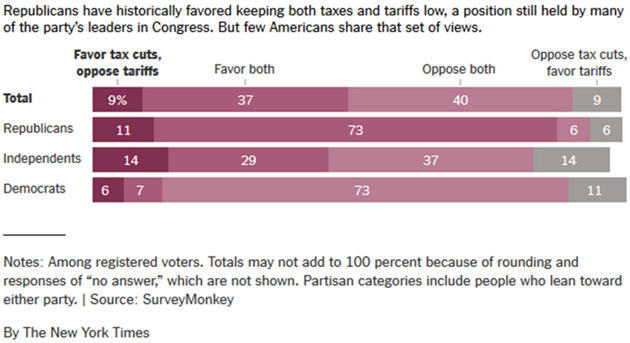

Source: CNBC Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross concedes that prices in the US will increase as a result of the new China tariffs put in place by President Donald Trump. However, Ross told CNBC on Tuesday, “Nobody is going to actually notice it at the end of the day,” because the hikes will be “spread across thousands and thousands of products.” “If you have a 10 percent tariff on another $200 billion, that’s $20 billion a year. That’s a tiny, tiny, tiny fraction of 1 percent [of] inflation in the US,” Ross said. That last part is true. Direct tariff impact will be a tiny part of overall inflation. But it’s wrong to say no one will notice. Plenty of people and businesses are already noticing. And when those tariffs go to 25% in a few months, $20 billion becomes $50 billion. That will be felt by the Walmart nation, and a long list of US corporations. Cato Institute trade scholar Scott Lincicome assembled a handy list for Reason magazine. It includes 202 companies with links to local news stories that describe how tariffs hurt them. Some are large, some small. This example from the metal industry: The New Hampshire metal-service center has been forced to turn down large orders from potential customers because it can’t source material due to tariffs. Browse the full list with source links here. Remove sharp objects from your vicinity when you do. The impact seems minor in many cases, but they add up. They spread, too: All these companies have customers and suppliers who depend on them. And we’re not even talking about the farmers who are already being hit with lower prices and higher costs. Think fingers of instability and sand piles. Some people say that the service sector is 85% of the economy, so tariffs can’t do that much damage. Much of that service sector serves people who manufacture stuff, buy food, and go to restaurants. It’s that sandpile thing again. The weirdest part is that tariffs could drive some of these companies to move production outside of the US. That’s the opposite of what we want. We already see it with Harley-Davidson, which is going to make motorcycles for the European market in a third country, thereby avoiding the retaliatory EU tariffs that would apply were they made in the US. Business-wise, that’s the smartest move Harley can make. But it will hurt US workers, not help them. Now, I can argue against tariffs until I turn blue, but I doubt it will have much effect. Yes, I voted Republican and that party controls both the White House and Congress. But I now find that I am in the minority. I am literally standing athwart my party yelling, “Stop.” A recent New York Times poll found that 79% of Republicans favor tariffs. Dear gods, have we come to this? In this graph, 73% of Republicans favor both tariffs and tax cuts while 6% oppose tax cuts and favor tariffs. I keep talking to more and more of my friends, nominally Republican, and we agree that we no longer have a party that represents us. Certainly, the Democrats don’t. I’ve shown the data in the last few weeks that independents are an increasingly small minority. When 79% of Republicans favor tariffs, and 80% of Democrats oppose tariffs, the world has truly turned upside down.

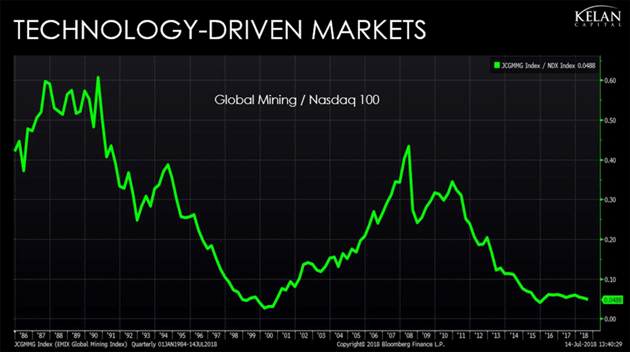

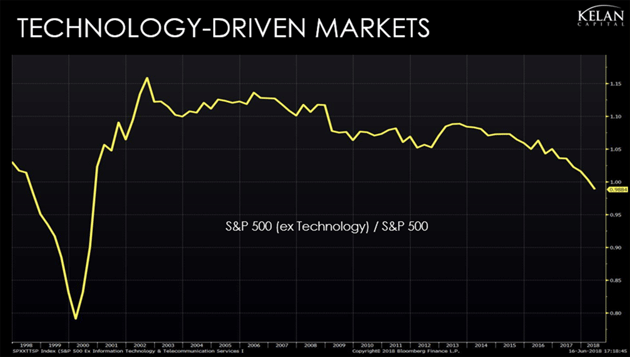

Source: New York Times So where is this going? Barring some titanic shift in the midterms, the president will stay on course and Congress won’t stop him. We should know in the next week or two what happens with NAFTA. Trump has a meeting with Xi in late November. My sources in China believe that something will happen to stall off the major effects of tariffs. But if Trump is looking for Xi to capitulate or somehow lose face, he is going to be waiting forever. Xi will use it to his favor. Further, China is growing their exports to other nations so fast that they can replace whatever they might lose to the US within a few years. Trump may think that China needs us, and to some extent they do, but we need them as well. The world works much better when everybody works together. For sins in many of my past lives, I have a seminary degree. One of the things we learned about was the First Great Awakening. The most famous sermon of that time was by Jonathan Edwards in 1741. Part of his fire and brimstone rhetoric, which today I find depressing, was the line, “…God that holds you over the pit of hell, much as one holds a spider or some loathsome insect over the fire…” While I do not believe that investors will fall into some fiery pit, I do believe that investors, especially those that are of the buy-and-hold bent, are held by a spider thread over a potentially angry market. A few quick charts and points. These first two charts are from Dr. Vikram Mansharamani, a good friend who is now teaching at Harvard. Basically, global mining stocks to the NASDAQ 100 is roughly back to where it was in 1999. If you own commodities, you’ve been getting your head handed to you. The second chart shows what the S&P would look like without technology stocks in them, which is to say they would be down.

Source: Dr. Vikram Mansharamani

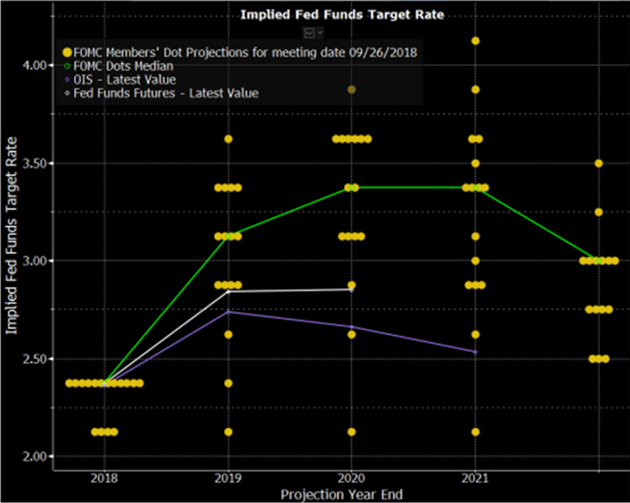

Source: Dr. Vikram Mansharamani Technology stocks, with high P/E ratios, are driving this market. Kind of like 1999. Next up, a few charts from Sam Rines. The first is the famous dot plot. Note that the median Federal Reserve member plans to hike interest rates by one full percent between now and the end of 2019. It is clear that they intend to hike another 25 basis points in December. And several members have been making speeches claiming that an inverted yield curve doesn’t mean anything. Evidently Chairman Powell is of the same mind.

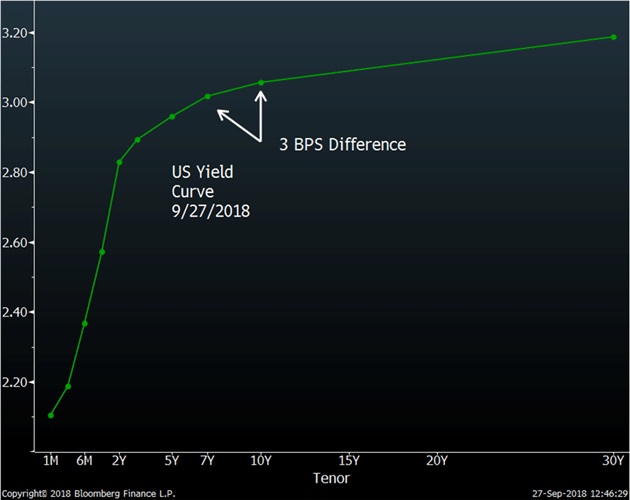

Source: Sam Rines Let’s look at the yield curve. Notice it is getting flatter towards the higher end and as Sam points out, there is only three basis points difference between the seven- and ten-year bonds. A full 1% increase would invert the yield curve.

Source: Sam Rines True story: In late 2006, I called the Federal Reserve economist who did the study noting that the only reliable indicator out of 20 potential indicators of a future recession was an inverted yield curve. The yield curve was inverted at that time, and I asked him what that meant. I swear to God, he said, “I don’t think it means we will have a recession this time.” And he then went on to explain why. He was wrong. In writing circles, that is known as an understatement. (Duke Professor Campbell Harvey had done the same study years earlier, and it was well known that an inverted yield curve has always preceded recessions in the US.) For mathematicians, it is well-known that if you have three large objects which have gravitational impact on each other, you can determine where they have been in the past, but you cannot predict where they will be in the future. It is called the Three-Body Problem. We are well beyond the three-body problem in economics. The Federal Reserve is raising rates while selling off $600 billion of Treasuries annually. The ECB and Bank of Japan are reducing their quantitative easing and the ECB may very well stop. God knows what’s happening in Italy. If the dollar doesn’t weaken significantly, emerging markets are in real trouble paying their debt. We are running massive deficits in the US and elsewhere in the developed world, and new technologies are putting old companies at risk. I can just keep going on and on. If central banks lose what Ben Hunt calls “the narrative,” then it is all over but the shouting. Right now, in central banks we trust. And in my opinion, the Federal Reserve is making a massive mistake in both raising rates and reducing their balance sheets at the same time. They’re going to lose control of the narrative. We’re going to see quantitative easing in our future on a scale that will shock everybody. Remember that I said it. You heard it here first. We have at least a seven-body problem, and there is no way to predict what will happen. And Trump throws in the uncertainty of tariffs and a trade war with China. He does this at a time when optimism on whatever index you want to look at is at an all-time high, unemployment is low, the economy is booming, and with Republicans hanging on by a bare margin with elections coming up, he could lose his ability to do or pass anything for the next two years. Not unlike 1929. You better have your hedges and strategy together. There is no reason for the US to go into recession unless a trade war begins to really impact the economy. It doesn’t have to impact a lot in order for future expansion plans by businesses to be impacted. I am getting nervous. Your wondering when we get back to some kind of centrist consensus analyst,   | John Mauldin

Chairman, Mauldin Economics |

P.S. Want even more great analysis from my worldwide network? With Over My Shoulder you'll see some of the exclusive economic research that goes into my letters. Click here to learn more.     | | Share Your Thoughts on This Article | | |

|