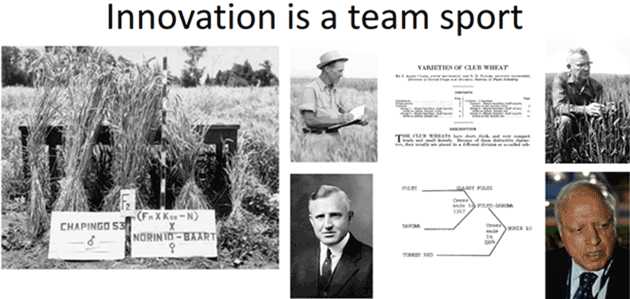

What Will Not Change By John Mauldin | Oct 31, 2020     “If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of Giants.” —Sir Isaac Newton, 1675 If you feel a bit overwhelmed, you’re not alone. A lot is happening right now. The US has a big election next week. We’re all on edge about the pandemic, which appears to be getting worse again, not just in the US but in most of the world. Germany and France are closing some businesses again and restrictions are rising in the US, too. This is hitting markets as investors see recovery sliding farther into the future. All that is important, and I’m sure next week we will talk about whatever happens in the election. But today I want to look at what will not change. And though I will make a few comments on the election below, I want us to think today about what we can look forward to with an optimistic and realistic vision. We can do this because something hasn’t stopped: human innovation. I keep saying that the business owners hurt by this pandemic will be back. People with the talent and drive to launch new enterprises won’t stop doing so, just like dogs keep barking. It’s just what they do. But it goes beyond business owners. Human nature drives us to break through the barriers standing between us and our deepest desires. Faced with problems, we find solutions. And faced with new problems, we find new solutions. This process never stops. It is at work even now, sometimes visibly but more often in a million small ways that add up. What do they add up to? Progress. And we can always make more because progress is an inexhaustible resource. Knowledge, as George Gilder says, is the ultimate currency which can never be destroyed. It can be used over and over again without ever depleting its supply. If you want to understand how innovation works, you should read Matt Ridley’s newest book, coincidentally titled How Innovation Works. Matt spoke at my Virtual Strategic Investment Conference this year (attendees can still view the transcript and slides, by the way) to rave reviews from all. No one explains better how innovation helps humanity move forward. As Matt explains, innovation usually doesn’t come from the solitary inventor screaming “Eureka! I found it!” It’s both simpler and more complex than that. Simpler because no one person really guides it, and more complex because more people are involved who often don’t even know each other. At SIC, Matt told the story of a wheat variety that was key to reducing global hunger. It's quite important, I think, to understand how people collaborate. So Norman Borlaug gets the credit for the short-strawed wheat that launched the Green Revolution in India and Pakistan, basically banishing famine from the world in the 1960s. But Borlaug got the idea from a man named Burton Bayles, who he met at a conference in Buenos Aires who told him about dwarf wheats. Bayles had got the idea from Orville Vogel in Oregon. Vogel had got the idea from Cecil Salmon, who was on Douglas MacArthur's staff in Tokyo at the end of the Second World War, and he got the idea from Gonjiro Inuzuka who had at an experimental station in Japan, bred these short wheats that grew much more vigorously and produced much higher yields. And then Borlaug passed the idea on to M.S. Swaminathan in India, who championed the development of these varieties. So it's very important, I think, to understand that innovation is a team sport, not an individual process. I bring this up because, back then, famine was a bit like our pandemic problem. It was costing lives and harming economies. No one thought it was good that people starved, but the problem seemed unsolvable. Governments did what they could, sometimes helping and sometimes making it worse. People thought we would just have to live with it.

Source: Matt Ridley But the solution was right there all along. The idea traveled through a series of minds that eventually brought it to the place it was needed. This is often how innovation works. In fact, Ridley’s book and history are replete with innovations occurring almost simultaneously across the world. Most famously, Alexander Graham Bell filed his patent for the telephone 30 minutes before his competitor. The great advances in math came from all over and almost simultaneously, even though we generally attribute them to a single mathematician. We are watching this play out in our own world. Several companies and countries are building rockets and other methods to take us into space. There are over 100 separate attempts at a vaccine which will lead to probably between 30 and 40 human trials to prevent COVID-19. The cooperation this has sparked will change the pace at which society will transform for the better. The “Green Revolution” Ridley mentions reached fruition slowly because communication was slower back then. Which brings us to the present. Innovation occurs when idea-filled people meet and interact. For most of human history, this kind of sharing could happen only when they met in person. Books and handwritten letters, while useful, lacked the interactive element. This is why innovation is so closely associated with urbanization. Large cities enable large gatherings, which enable the kind of interaction that leads to innovation. Even today, with all our communications technology, new technologies come from places with concentrations of talented people like Silicon Valley and Shenzhen. Or used to. One of the pandemic’s many regrettable consequences is the impact on city life. The same crowds that once attracted people now repel them. Companies that once built elaborate offices akin to mini-theme parks (because they know keeping people happy at work raises their productivity and helps spread ideas) are now allowing and even encouraging work-from-home arrangements. From a health perspective this may make sense, but what will it do to innovation? We’re going to find out. The good news is this problem is itself being innovated. Entrepreneurs and managers are finding new ways to use existing technologies like Zoom, Slack, Team, WebEx and other remote work applications. More sophisticated platforms are coming, using virtual reality techniques to create the kind of meetings and encounters that once occurred spontaneously. I don’t think we will go back from this once the pandemic is over. Some organizations will move to hybrid work models. Maybe most people will work from home, most of the time, but occasionally the team will gather for an in-person event. Paying for travel and accommodations will still be less than office space would cost. (Of course, this means office space will be repriced or new uses for it will be found. Already, we are seeing plans for empty malls being turned into fabulous living environments.) It also helps greatly that government is getting out of the way. For example, the technology to conduct many doctor visits by phone or video isn’t new or complicated. We just couldn’t use it because state laws sometimes prohibited it, and Medicare rules wouldn’t pay for it. That suddenly changed this year. Reports suggest it’s working pretty well. Neither doctors nor patients will want to go back. Now, think about what that does. If you have a medical problem, you want a physician who specializes in it. With remote medicine, you can look more widely and are far more likely to find someone with exactly the expertise you need. This should improve healthcare even if technology stays the same, which it won’t. It will get better, too. All because a pandemic upended the established order. I think we may be on the cusp of a sweeping change in human organization. Instead of clustering together in giant concrete boxes so we can be close to the people we think we should know, we will cluster virtually, with exactly the people we need to know. Teams that need expertise will be able to access it wherever it is. Severing this tie between “where we work” and “where we live” could have profound consequences. That’s my hope, at least. We will find out in the next few years whether technology can replace the serendipitous personal encounters that often spark innovation. Let me make a few “happy” predictions for the next 10 years and then a few more sobering ones. Like all such lists of predictions, several will be wrong but at least you will get the idea of where I think we are going. - We are going to see major advances in healthcare. I mentioned a few weeks ago the invention of Far UVC which doesn’t penetrate the skin or eyes of human beings, but will kill viruses and bacteria. Cancer will become a nuisance, rather than life-threatening and expensive. Treatment will likely be done in a doctor’s office rather than a hospital.

Advanced MRI scans will be done annually or at least every two years, with artificial intelligence to help interpret them. Treatments that will look like the “Fountain of Middle-Age” will help us make it to the time when we can turn our own biological clocks back. There will be treatments for obesity and heart disease. Muscular regeneration will be much easier. These studies and a thousand others are happening all over the world. Picking the winners today is difficult, but the true winner will be humankind. - We will see a continuing move to renewable energy, not because it is mandated under some climate policy, but because it will be cheaper. There are already places where solar energy costs less than conventional methods. I believe by the end of the decade solar will be cheaper than even natural gas.

It would not surprise me, given the number of research projects in motion, if we see new renewable energy technologies that will even outpace solar. Battery research and technology is improving (finally) and will make solar ever more viable. - We will be moving to electric cars (or their hydrogen fusion cousin) by the end of the decade. Urban dwellers will either own cars in co-ops or simply opt to use ride-sharing services.

- Self-driving autonomous cars will be ubiquitous. Half the cars manufactured in 2040 will be autonomous. This will have a profound impact on the transportation business much sooner though, as the millions who are currently employed as drivers will have to find new sources of income. But it will also reduce the number of deaths on the highways and car wrecks that have to be repaired, lower insurance rates, and a dozen other things.

- New agricultural technologies, including a whole new generation of seeds and plants, will make food cheaper, more nutritious, and hardier, without the “GMO” stigma. This will have more impact than the Green Revolution did 70 years ago. Imagine plants tailored to produce meat substitutes or reduce allergic reactions.

- Of course, computers will be incredibly fast and we will begin to see the beginnings of the quantum computer revolution. That extra speed will make artificial intelligence, communications networks, the Internet of Things, robotics, and a dozen other technologies far more viable.

- You cannot begin to make predictions without mentioning the improvements that the blockchain will make use of.

- And while the pandemic has caused a major setback in worldwide poverty, I expect that to be short-lived. We will see the number living in poverty steadily decrease, as it has for the last 50 years.

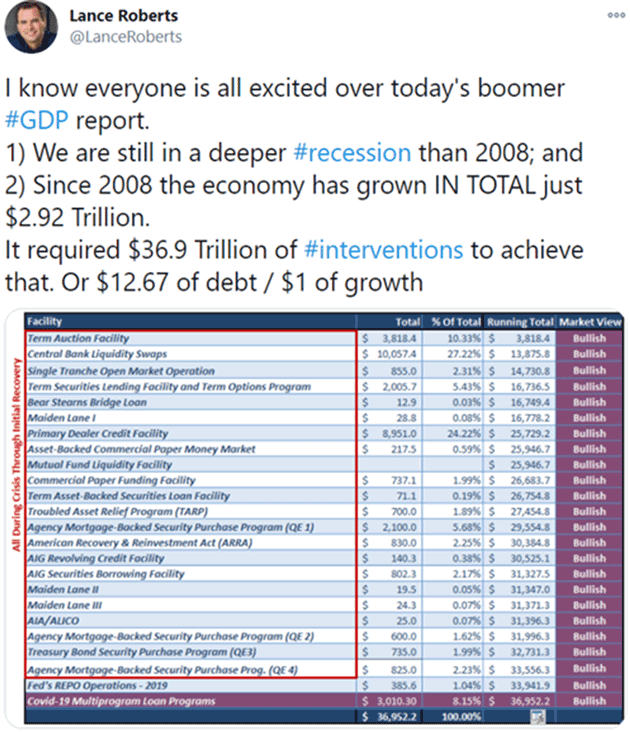

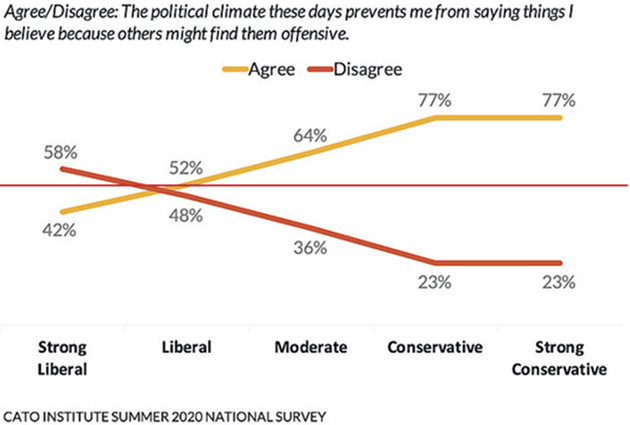

I can go on to list many more innovations which will develop over the next 10 to 20 years, and would still miss the ones that nobody has yet imagined. The innovation cycle that began with the Industrial Revolution has gone through wars, economic crisis and depressions, a wide variety of governmental systems, and in numerous countries. Whatever the outcome of this week’s election, that won’t change. That also means there will be lots of opportunities for entrepreneurs and investors. Now, it’s not all sunshine and rainbows. Whoever wins next week will be faced with the $3 trillion deficit in fiscal 2021. And the Federal Reserve interventions and government programs have not been as effective as one might think. This from my friend Lance Roberts on Twitter:  One could take issue with his choice of interventions, but even if you cut them by half (I really don’t think you could), it would still be $6 of interventions for every $1 of GDP. The next president will have to face this reality. We are approaching the limits of government intervention. Let me take an out-of-consensus view. I think the 2024 election is going to be far more important than this one. We will see the final gasp of Neil Howe’s The Fourth Turning, always the most tumultuous period in American and Western history, at the same time as George Friedman’s The Storm Before the Calm (a very powerful book). I think the latter half of this decade could be even more divisive and economically frustrating than the period we are in now. Everything I just wrote has a giant presupposition: Ideas come from people. What if that limitation disappears, too? Humans have ideas because humans are intelligent. Our senses collect information, our brains process it, and new ideas emerge. We do this better than any other species and that is why we have civilizations and economies. The never-ending innovation process is now replicating itself. Today we have “artificial intelligence” systems that operate much like we do, only faster. They can take giant data sets, look for patterns and connections, and find solutions in unexpected places. It looks a lot like human innovation, except it’s not human. These AI technologies are still in their early days, but they’re progressing fast. Some people fear this. I don’t. Humans design the machines to serve human needs. I don’t expect a robot apocalypse. I expect a new kind of teamwork as our machines become not just tools, but a kind of business partner. This is going to be a long-term trend and I want to begin following it more closely for you. We’re exploring some ways Mauldin Economics can do that. To do this right, we need your input. You can help by taking this short, three-question survey. Many thanks. I have spent the last month or so talking with friends whom I consider to be political insiders trying to get some insight into the election. We see events that are truly unprecedented. It is now highly likely more people will vote in this election percentage-wise than any election since 1908. I don’t know what that means for the outcome but clearly people are extraordinarily passionate. Early voting has been historically record-breaking. I am a student of history and I recognize there have been periods when the country was just as deeply divided and vilified both politicians and their opponents just as much as we are doing now. Our republic survived all those periods. But that’s small comfort. It is no fun to actually live in those times. The worst part is that these passions inhibit discussion with those we oppose. A Cato Institute survey shows only 62% Americans feel comfortable expressing their political views, down considerably from the same survey in 2017.

Source: Cato Institute Significant numbers of both conservatives and liberals would support firing people who donated to the opposite campaign. Indeed, 32% of people feel their political views could harm them at their work. This has led to a self-censorship and lack of serious and friendly dialogue, which is deeply concerning to me. Friendly, even if spirited, debate is the basis for developing common political consensus. I don’t see that today. I’ll close with a quote from George Friedman’s latest letter where he expresses my own concerns but more eloquently. Not all is lost, of course, but what has been lost is the idea that reasonable people can disagree over important matters and remain friends. That has become difficult if not impossible in the United States. It is not the political passion that troubles me. It is good for politicians to be demonized, to be forced to the edge and to see what they are made of. What troubles me is the hatred and contempt we show our fellow citizens who might once have been friends. I voted for Ronald Reagan, and I had friends who voted for Jimmy Carter. We disliked the candidate but not each other. The same could be said of the election between Barack Obama and John McCain. I am sanguine about the future of the republic, but our inability to remain friends with those who vote differently is growing and alarming. I believe this will change when we have our final flashpoint of political angst later this decade, accompanied by The Great Reset. We will see more social cohesion just like First Turnings have for the last 400 years. But getting to that point won’t be fun. So we need to remember to focus on what we can do in our own areas and take care of family and friends. And seek out the opportunities that will come our way. They will be many and powerful. So I actually look to the future with great optimism and hope, no matter who wins the election this coming Tuesday. Yes, things will change, but we will all adapt. Let’s do so in the spirit of optimism rather than fear. That always works better. First of all, I want to thank the scores of people who sent me advice and connections to neurologists in Tulsa to help deal with Trey’s issues. I was expecting maybe five or six replies. We were simply overwhelmed. Trey is getting treatment and we hope for the best very soon. Readers like you are one reason I am such an optimist even as I recognize the economic and political trauma in our future. The genuine willingness to help others, even when there is nothing to be gained from it, gives me hope for humanity. I’m very long humanity. Thank you for taking the time to read these letters. August passed, and I did not mention that it was this weekly missive’s 20th anniversary. I’ve enjoyed every moment, but mostly I’ve enjoyed your responses. And with that, I will hit the send button and wish you a great week! Your so very grateful for all his blessings analyst,   | John Mauldin

Co-Founder, Mauldin Economics |

P.S. Want even more great analysis from my worldwide network? With Over My Shoulder you'll see some of the exclusive economic research that goes into my letters. Click here to learn more.    | | Share Your Thoughts on This Article | | |

|