Consumers, however, show little interest in cooperating. That’s not always voluntary; people have to buy food, gasoline, and other necessities. The other purchases that sustain US living standards are proving sticky as well. We have seen Paree and no longer want to stay down on the farm.

That being the case, at least as far as the Fed seems concerned, demand must be reduced the hard way—involuntarily. Enough people need to lose enough income that they will have no choice but to reduce their spending. That means taking away their jobs and/or cutting wages. “Nothing personal,” Jerome Powell would no doubt say, but the effect is the same… or would be if the Fed could actually generate unemployment. That is proving a slow, difficult process.

Last week’s JOLTS report showed US employers listing 10.1 million openings at the end of August—down over a million from the prior month, but still quite strong. The same agency’s data showed 6.0 million unemployed Americans that month, meaning employers needed 4.1 million more workers than were available.

That’s good news for job seekers—at least those who qualify for the available openings—because they can demand better wages and working conditions. For the same reasons, it’s a challenge for employers. But it’s a serious problem for the Fed. It means their main demand-suppression tool is broken and controlling inflation is thus a lot harder.

Today I want to talk about why the labor market is so out of balance. Some of this is new and some has been brewing for many years. We will end with some commentary on yesterday’s unemployment report.

| [High Conviction Investor Now Accepting New Members]

This service from Mauldin analyst, Thompson Clark, targets high-upside opportunities in a responsible way and gives investors the power to supercharge their portfolio with repeat winners. All without taking unnecessary added risk that could destroy their portfolio. Click to read more. |

“Full employment” sounds like a good thing. Everyone’s working and happy. But that’s not actually how it works.

Some unemployment is normal. People who could be working choose not to work for all kinds of perfectly legitimate reasons. It’s often temporary; they leave one job and take a break before starting the next one. At any given time, some workers will be technically “unemployed” but not necessarily in distress.

Economists call this “natural unemployment.” Most see it as actually preferable to full employment because it is less likely to cause inflation. A fully employed economy has no slack, which tends to raise prices. The ideal state is something called NAIRU—the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment. That’s a theoretical point close to full employment, but not close enough to raise inflation. (The concept of NAIRU has become debatable recently, but that’s another discussion.)

Defining these things raises all kinds of measurement issues, of course. We don’t really know what NAIRU would be but the US economy is obviously nowhere near it. Every consumer-facing business has a “We’re hiring!” sign in the window. Wages that would have been extremely generous a few years ago are now scoffed at. All kinds of prices are rising. Instead of NAIRU we have AIRU: an accelerating inflation rate of unemployment.

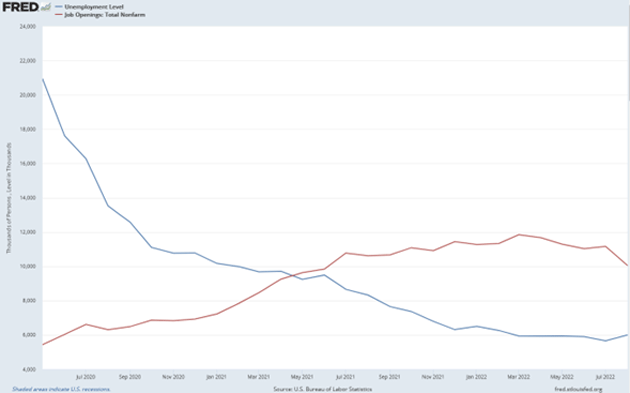

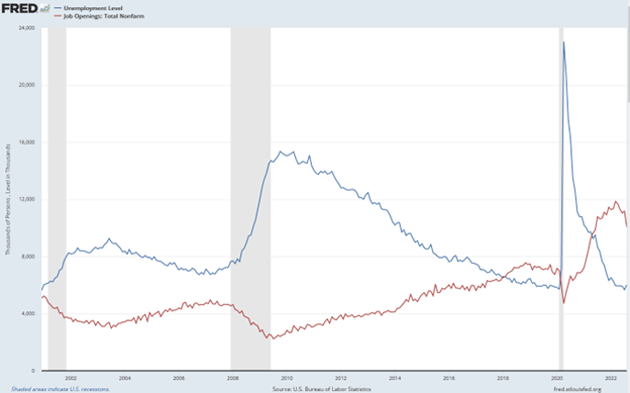

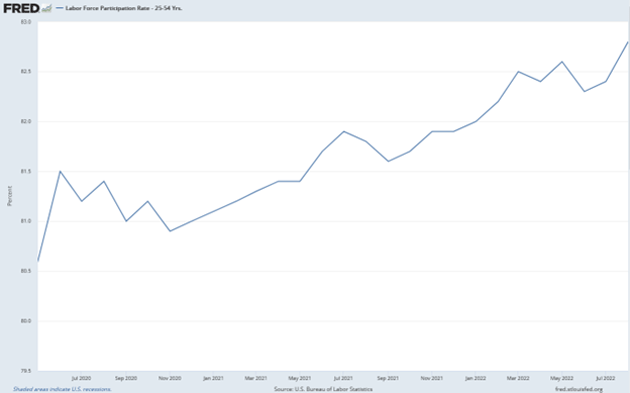

In other words, the US has the opposite of a “jobs recession.” Jobs are more plentiful than workers, at least according to the JOLTS data. Here’s a look at recent history. (I’m starting this chart in May 2020 to avoid the early COVID distortions.)

Source: FRED

After the short COVID recession, the number of unemployed workers (blue line) fell steadily while the number of job openings (red line) gradually rose. The lines crossed in May 2021, which should have been a hint (#7 if you’re counting at home) that inflation might not be so transitory. And indeed, it got worse from there as employers had to raise wages in addition to all the other rising costs—shipping, materials, energy, etc. And even higher wages weren’t enough. The workers they sought to attract didn’t exist or weren’t seeking jobs.

This may be changing. You can see in the chart how job openings peaked in March of this year and declined over the last few months. This may be an early effect of the Fed’s tightening policies. Similarly, the number of available workers also seems to be stabilizing.

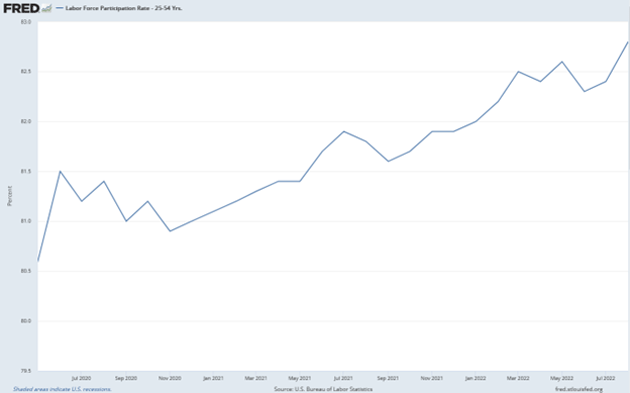

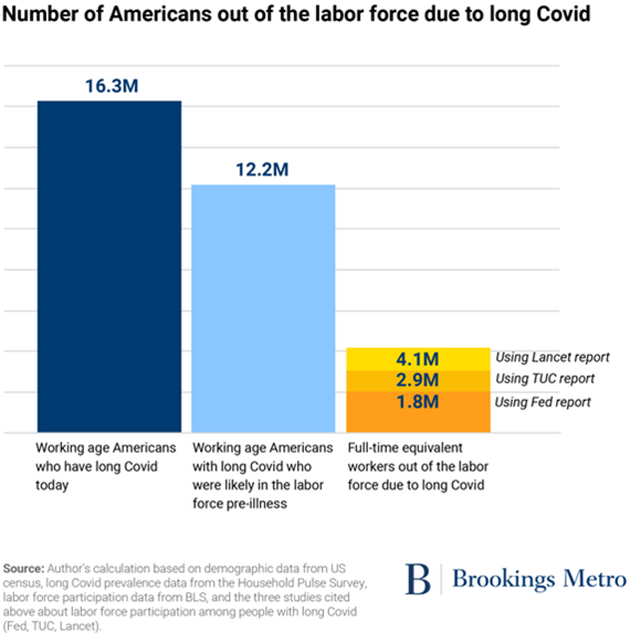

For those two lines to cross again, bringing the economy closer to NAIRU, we need some combination of less hiring and more available workers. The latter is actually happening as people re-enter the labor force. This chart shows how the “prime age” (25‒54) participation rate has been growing.

Source: FRED

At the end of 2019 prime age participation was 82.9%, meaning 82.9% of those aged 25‒54 either had jobs or were seeking jobs. This fell briefly below 80% when COVID arrived then slowly climbed back. As of September 2022, it was 82.7%, so almost completely recovered.

Yet we still have the giant jobs gap. Why is that? Partly because workers below 25 and above 54 are still pretty important. Dave Rosenberg thinks early retirements over the last two years explain a big part of the labor shortage. That’s partly but not entirely due to COVID health concerns. Some of it is because the rising market boosted portfolios, making people think they had enough assets to stop working. As markets drop many are learning that’s not the case, so some may trickle back into the job market (or try to).

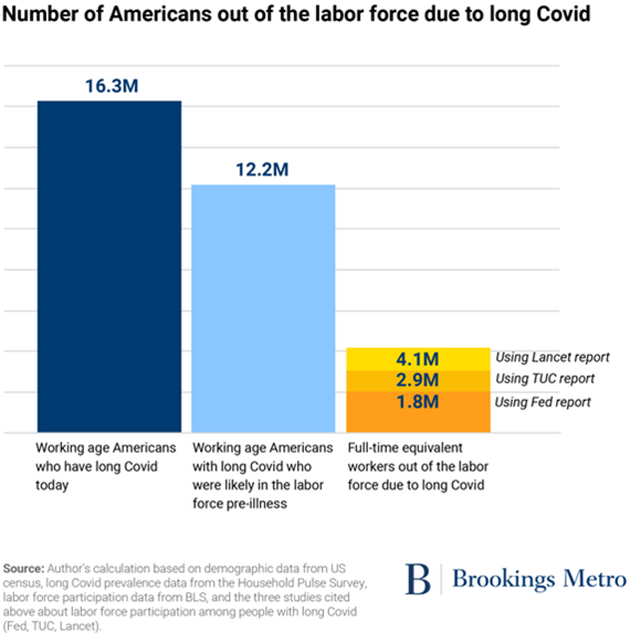

“Long COVID” is probably another major issue, though its impact is hard to measure. A recent Brookings Institution study estimated somewhere between 1.8 million and 4.1 million Americans who would otherwise be in the labor force are instead not working due to long COVID.

Source: Brookings Institution

This can be a problem even if the people aren’t fully disabled. Maybe their symptoms come and go, but they’re still unable to work a significant part of the time. They think they’re getting better, they want to work, then they get sick again. It’s highly frustrating on a personal level. Economically, we are all losing the value they could contribute.

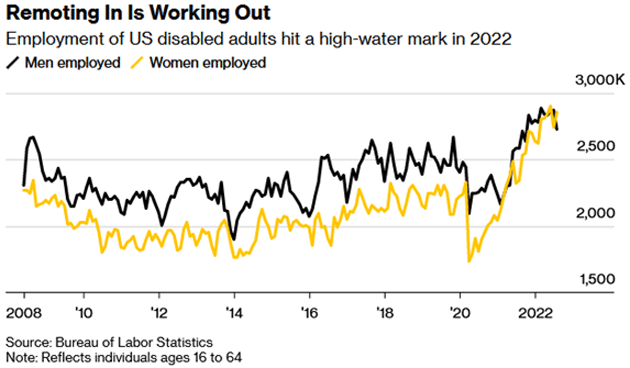

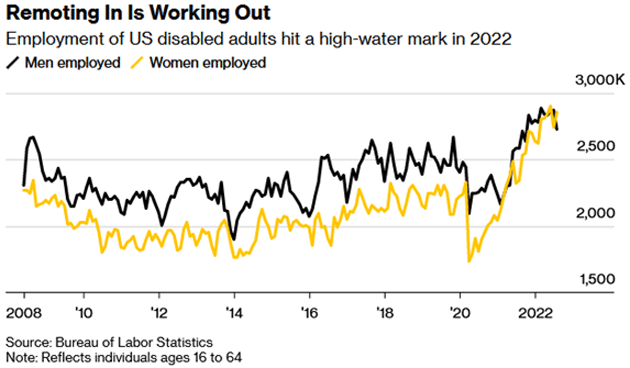

Oddly, though, COVID changes are also offsetting some of this. Growing acceptance of work-from-home arrangements is breaching a barrier that had kept many disabled people out of the workforce: commuting. The number of working disabled adults has climbed sharply since 2020, particularly for disabled women.

Source: Bloomberg

This brings some much-needed labor force growth, and of course it’s wonderful these people can participate more normally. But it’s still not enough. We have bigger, longer-term problems.

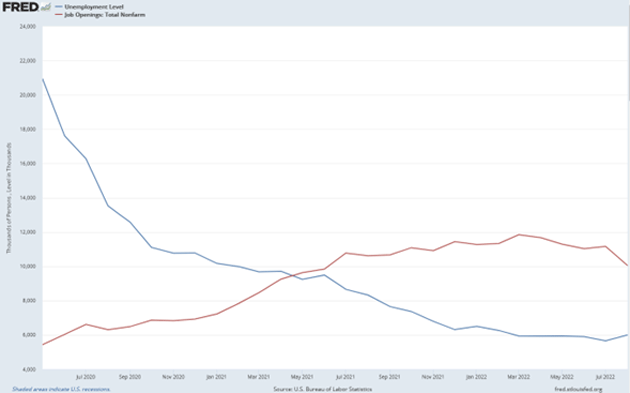

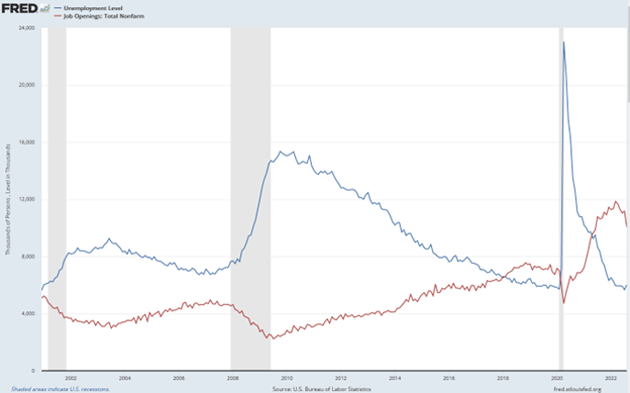

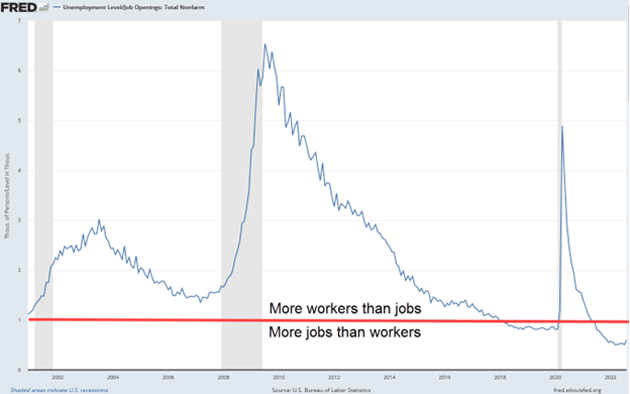

The Bureau of Labor Statistics began publishing job openings data in December 2000. That’s the source of the first chart above. Here is a longer-term look at the same series.

Source: FRED

Starting at least in December 2000 and presumably much earlier (though we don’t have hard data), the number of unemployed workers always exceeded the number of job openings. The gap widened in recessions but existed even in good times. That’s “natural unemployment.”

But look on the right: the lines first crossed not when COVID arrived, but more than two years earlier in January 2018. Check the media archives and you’ll see a lot of stories about a labor shortage in 2018‒2019.

The labor shortage didn’t start in the pandemic era. It was already there well before. The virus and our response to it seem to have interrupted a preexisting trend which is now resuming.

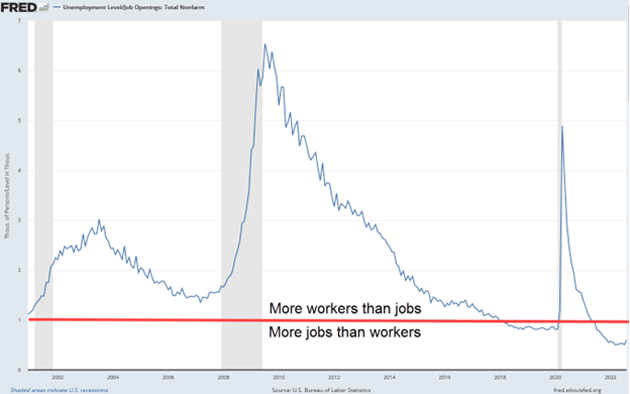

You can see this more clearly when we express the same numbers as a ratio. Readings greater than 1 mean the economy had more unemployed workers than job openings, Readings below 1 mean job openings exceed the quantity of unemployed workers. I added a red line to highlight the change.

Source: FRED

Obviously, the labor shortage is greater now than it was before COVID, but it was already there. That ratio was falling steadily from 2010 to 2018 when it crossed below the red line. Where would it be now if the pandemic had never happened? I suspect not far from where it is.

What we’re looking at is more than a policy problem or a health problem. Yes, COVID removed a bunch of people from the labor force. Yes, the various fiscal and monetary responses made some of it worse. But all that is minor. The real problem is demographic.

Note the ratio peaked in 2010. Is it coincidence that’s when the oldest Baby Boomers (born 1945) turned 65? I think not. Our largest generation of workers started becoming eligible for retirement that year, and more each year thereafter.

Of course, not all Boomers retired; I haven’t and don’t intend to. But many did, and it had an impact on the labor force. That wouldn’t matter so much if the retirees were being replaced with younger workers (and/or immigrants) entering the labor force. Those numbers were not sufficient to close the gap, particularly as more retirees live longer and keep generating demand.

This labor shortage isn’t temporary. It’s structural, it’s demographic, and it isn’t going away. It may improve somewhat, but even a return to 2018 conditions won’t restore the “normalcy” employers want.

Macro analysts talk about “regimes”—currency regime, monetary regime, etc. They use the word to mean something like “the currently prevailing wind.” The wind can change for short periods but eventually the regime reasserts itself. On rare occasions, there is “regime change.”

I’m an early Boomer, born 1949. I turned 73 last week. My career started in the mid-1970s, about the same time as a major culture change occurred with women entering the workforce. Combined with my generation looking for jobs, the expanded labor supply helped create a time of high unemployment. It persisted into the 1980s. Applying for any kind of job was a competitive thing. We all knew and expected it.

The hiring side had its own expectations. List any kind of job opening and you would get a ton of applicants. Ten years ago, we advertised for a personal assistant and received 300+ applications, many of them over-qualified. Sorting through them was a chore but we had to do it. That’s just the way it was—the jobs regime we knew. Workers and employers all knew the drill.

For employers, the days of picking the cream of the crop are gone. The crop is smaller now. You take what you can get, and you pay more for it. We may see temporary relief from time to time when the economy weakens, but the labor regime has changed.

This regime change will have other effects I think we have not yet discerned. In any case, it greatly complicates monetary policy. Generating the kind of unemployment that reduces inflation pressure is much harder when labor is already scarce. Paul Volcker didn’t have that problem. Jerome Powell does, and it makes his job much harder than Volcker’s.

Are the days of ultra-low inflation are gone? Powell will eventually get it down to a more tolerable level, but the Fed will have to change that 2% inflation target. It is unreachable in the short term and maintaining it against all evidence makes them look powerless.

Labor Department data released Friday morning showed the US economy added 263,000 jobs in September, a slower pace than the previous month but probably not enough for those who want the Fed to pause sooner rather than later.

My good friend Barry Habib sent me the following gleanings from the household survey. This made me raise my eyebrows. Remember, the household survey is different from the establishment survey. Quoting:

“Jobs Report Insights

-

There were 204,000 job creations in the Household Survey, but almost all of them were from older men.

-

45‒54: 223,000 job creations

-

55+: 355,000 job creations

-

Total = 578,000… which means losses of 300,000 in all other categories

Household Survey

-

Unemployment rate declined from 3.7% to 3.5%

-

204,000 job creations, but labor force decreased 57,000—much of the decline in UR was for the wrong reasons.”

John here. Not certain what to make of that, but just thought it odd. And speaking of odd, separately, there were 382,000 new employees without high school degrees.

In fairness, the household data is notoriously volatile. Next month it might show a very different trend. But the 3.5% unemployment is what got the market’s initial focus. That seems to give the Fed more running room. The market wants softer data so the Fed can pause. This was not it.

Peter Boockvar summing it up:

“Bottom line, while the data was about as expected, the drop in the unemployment rate is seemingly what the markets are obsessed with because of what it means for the Fed. This even though job hirings have decelerated now for a 2 nd month with August and September averaging 289K and I expect this to continue. Because of a big July, the 3-month average job gain was 372K vs. the 6-month average 360K and the 12-month average of 474K. As stated, wage gains are no longer accelerating but hanging in there with 5%-type gains, still below the rate of inflation however. As for the still-low unemployment rate and when combined with the low level of initial jobless claims, the pace of firings remains muted and this of course gets the Fed all fired up about continuing with its aggressive rate hikes.”

(By the way, Over My Shoulder members got to read Peter’s full analysis on Friday morning. You could do the same by joining them.)

I think 75 basis points is very much on the table for the November meeting, exactly one week before the mid-term elections. What does that mean? How much does the Fed want the market to be happy one week out? Conventional wisdom says they would pay it no attention. I hope this to be the case.

I am still in the camp that they’ll keep raising rates until something really breaks. A 5% Fed funds and 5% unemployment should be more than enough to kill inflation. And a few other things…

As most of my readers know, I have been associated with Steve Blumenthal and CMG for many years. I am an investment advisor and serve as CMG’s chief economist. We favor an endowment-like investment approach investing our clients’ money in a far different manner then most money managers. We build CORE portfolios making liberal use of alternative strategies, favoring well-collateralized short-term private credit, select trading strategies in addition to traditional high and growing dividend stocks to create balanced all-weather portfolios. We then allocate a small percentage of a portfolio to what we call EXPLORE investments. These are very risk-on type of investments in select venture capital and late-stage private equity where we seek asymmetric risk/reward opportunities.

My view remains that we are heading down a path towards what I call The Great Reset. I foresee a bumpy ride for traditional investments given current high equity market valuations and low yields on traditional fixed income. As I like to say, friends don’t let friends buy and hold index funds. But that doesn’t mean you can’t find opportunities.

If you'd like to learn what I am doing for my own investments, and if you have a net worth of $1 million or more and are interested in learning more, simply click this link .

Please know that the privacy of your personal information is of the utmost importance to me/us, as we know it is to you. Lastly, if you feel inclined, there is a box on that page where you can ask a question or leave me or Steve a short note. I hope you find the information helpful.

Shane and I are off next week to go to the Cleveland Clinic together. Lots of poking and prodding but we will enjoy the companionship of Dr. Mike Roizen. There is a growing chance I will go to Houston and Rice University for my 50 th class reunion. I will be in Denver on November 17 for the annual CFA dinner and a conversation with great friend Vitaliy Katsenelson. Then back to Dallas for a few days before flying to Tulsa for Thanksgiving.

I am looking forward to getting to see friends and speaking to groups. I don’t miss the airports, but I do miss the people. And with that I will hit the send button. Have a great week! And don’t forget to follow me on Twitter. I am starting to be fun!

Your glad to be employed analyst,