|

To investors,

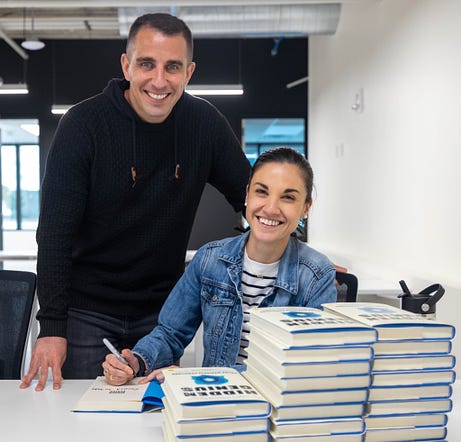

There is something special about watching your friends and family accomplish their dreams. My wife, Polina, spent the majority of her life dreaming about being a writer. There were two boxes to check in this pursuit — become a journalist at a big media outlet and write a book.

After spending more than 5 years as a journalist at Fortune Magazine, it was time to check the second box. Polina spent months putting together her first book, which is titled Hidden Genius: The secret ways of thinking that power the world's most successful people.

The book officially launches to the public today. I have read it more times than I would like to admit and it is fantastic. Below is an excerpt from Hidden Genius on clear thinking. If you like this excerpt, or simply want to support Polina, please consider buying the book today to help her march towards #1 on the sales charts.

Today is an exciting day in the Pompliano household. I hope that each of you is able to experience the joy of watching those you love accomplish their dreams as well.

Do you really believe what you believe? What would it take to change your mind?

In 2019, I interviewed Blackstone CEO Steve Schwarzman, a man who has been called “the master of the alternative universe” because Blackstone made its name by investing in alternative assets—investments that were once considered “non- traditional,” like hedge funds, private equity, and commodities.

But there’s an alternative to the alternatives. Today, a new cohort of investors is plowing cash into digital assets such as Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies.

When I asked Schwarzman what he thinks about Bitcoin, he said, “I don’t have much interest in it because it’s hard for me to understand. I was raised in a world where someone needs to control currencies.”

Fair point. But his answer made me think about all the things we believe because of our background, our family, our job, our economic incentives, and our political affiliations. And it’s only natural that our beliefs evolve over time, right?

Well, not really. In today’s society, changing your mind isn’t as celebrated as you might assume. In politics, you’re called a flip-flopper. In real life, you’re a hypocrite. On Twitter, you’re god knows what.

So we stick to our beliefs—no matter how wrong or outdated—and forge ahead. Why? Because we’re searching for social acceptance and identity validation, much more so than truth. As James Clear wrote, “Convincing someone to change their mind is really the process of convincing them to change their tribe.”

Changing your tribe may seem like a herculean task, but there’s value in seeing reality more objectively. Clear thought prevents us from falling for false narratives, keeps our ego in check, and most importantly, allows us to think for ourselves.

Legendary investor Charlie Munger has an “iron prescription” to make sure he doesn’t become a slave to his beliefs. “I’m not entitled to have an opinion on this subject unless I can state the arguments against my position better than the people do who are supporting it,” he says. “I think only when I reach that stage am I qualified to speak.”

BATTLING BLIND BELIEF

In 2006, Sarah Edmondson paid $3,000 to participate in a five-day “executive success program” in Albany, New York. The workshop was created by NXIVM, a personal development company that boasted its “patented technology” could help ambitious people like Edmondson become more successful in their personal and professional lives.

On day three of the five-day training, Edmondson had a “breakthrough”during a session on self-esteem and limiting beliefs.

Over the next 12 years, Edmondson went on to become a top-ranking member at the company, responsible for opening a chapter in Vancouver, recruiting new members, and teaching seminars to spread the group’s philosophy. She finally gained what she had been seeking—purpose and connection.

But she was being led down a dangerous path.

Eventually, Edmondson was told that as part of a women’s empowerment initiation ritual she’d have to get a small tattoo of a Latin symbol. Along with other female NXIVM members, she was branded with the initials that belonged to the founder of the organization.

Edmondson believed she belonged to a personal development company. Instead, she had been part of a cult that engaged in sex trafficking under the guise of mentoring and empowering women. She says figuring out that the symbol bore the initials of the founder “was the biggest wake-up call.” She left the organization and filed criminal complaints against the leaders.

Edmondson’s story is detailed in a disturbing documentary called The Vow. After watching it, I couldn’t stop thinking about the fallibility of the human mind and the slippery nature of identity and belief.

Barry Meier, the New York Times reporter who broke the NXIVM story, said, “The central thing that I took away from [this story] was how extraordinarily vulnerable we are as people, and how even people who, on the surface, are bright, capable, talented, and successful, have this intense vulnerability. That vulnerability is available for someone to exploit.”

Right about now, you’re probably thinking: “Oh please. I would never get roped into something like this.” But ask yourself: When’s the last time you challenged an institution— political, religious, even astrological? (According to the Pew Research Center, more than 60% of American millennials believe in New Age spirituality, which includes reincarnation, astrology, and psychics.)

In a dynamic, ever-changing world, we have to learn how to contend with uncertainty. And when we don’t have answers, it’s easy to turn to sources of authority to ease our anxiety about the future—or to see people or institutions as being authoritative, like NXIVM, when in fact they’re merely manipulative.

Not every cult has branding rituals or megalomaniacal long-haired cult leaders. There are cults all around us in the form of echo chambers that we voluntarily (and sometimes involuntarily) join. From the news we trust to the social media groups in which we participate to the friends with whom we communicate, many of us absorb ideas from sources who tend to share and reaffirm our existing opinions.

Many times, we find ourselves digging our heels in the ground even when there’s evidence that contradicts our belief. This feeling of believing that you should believe something—despite realizing it’s ridiculous—is what philosopher Daniel Dennett calls “belief in belief.”

This phenomenon isn’t only reserved for religions or cults. It also appears in everyday life. Dennett explains that the entire financial system hinges on belief in belief. For instance, politicians and economists realize that a sound currency depends on people believing that the currency is sound—even if there’s proof to show otherwise.

Why does this happen? In large part, because the human brain craves predictability, and it feels betrayed when trusted sources change their positions. To ease the discomfort, we’ll go to great lengths to make sense of the inconsistency.

In 2008, Howard University psychology professor Jamie Barden conducted a study to determine how people processed inconsistent behavior of political candidates. He told a group of students—half of whom identified as Republican and half as Democrat—to judge the behavior of a hypothetical guy named Mike.

The students received the following information about Mike: He had organized a political fundraiser, had a little too much to drink, and crashed his car on the way home from the event. A month after the incident, Mike went on the radio and preached to listeners about how no one should ever drive drunk.

There’s two ways to interpret Mike’s behavior: 1) That he is a hypocrite or 2) that he learned and grew from his mistake. So how did the participants in the study judge Mike’s actions?

Here’s the key detail: Half the time Mike was described to the students as a Republican and half the time he was described as a Democrat.

When Mike was presented as being of the same political party as the study participant, only 16% of the participants judged him to be a hypocrite. But when Mike was presented as being from the opposing political party, 40% judged him to be a hypocrite.

In other words, when someone acts in unpredictable ways, we don’t change our beliefs. We simply change our interpretation of their actions to make them more congruent with our existing beliefs.

Psychologist Philip Tetlock conducted a famous study in which he concluded that the political world is divided into two groups of people whom he calls foxes and hedgehogs. (Based on the ancient Greek aphorism, which says the fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing.)

Tetlock says that some leaders behave like hedgehogs: They have one big worldview based on what they see as a few fundamental truths, and these people are highly consistent. So a free-market hedgehog uses the lens of the free market to understand all types of different things. The foxes, on the other hand, tend to be very inconsistent because they are guided by drawing on many diverse strands of evidence and ideas.

So Tetlock conducted a massive study over 20 years to look at how accurate “foxes” and “hedgehogs” were in predicting what the future was going to look like. In the end, he found that over time, foxes tend to be much more accurate than hedgehogs.

Why? Because for a fox, being wrong is an opportunity to learn new things, so they are much better equipped to deal with the complex and unpredictable things life throws their way.

Tetlock’s work has challenged the idea of what it means to be an expert. We may think of experts as these knowledgeable figures who are entrenched in their beliefs and never flip- flop. Rather, Tetlock says, the experts whose predictions often turn out correct are those who frequently use terms like “but,” “however,” and “although.” That’s why cult leaders are often described as charismatic and persuasive—they present the world in black-and-white terms with little room for nuance.

After leaving NXIVM, Edmondson became more mindful of the information she consumed on a daily basis. She began to inquire and embrace skepticism in an effort to get closer to the truth. “I’m at the point where I will never follow something blindly,” Edmondson said. “I have to know why I’m doing what I’m doing, because I did follow blindly for 12 years, and look where it got me.”

Approaching the world with a healthy dose of intellectual humility and skepticism is a good thing—even if it may not be popular. As historian Daniel J. Boorstin said, “The greatest obstacle to discovery is not ignorance—it is the illusion of knowledge.”

This was an excerpt from Polina Pompliano’s new book, Hidden Genius, which officially launches today. Each copy that you purchase today will help Polina rank higher on the sales charts, which ultimately drives even more sales. Let’s take Polina to #1 so I can claim that I was helpful for once :)

Hope you all have a great day. I’ll talk to you tomorrow.

-Pomp