|

The other day, I was meandering down the street when I noticed: the jade plants are blooming! They have happy little flowers, white stars, tinged with pink.

Now, a jade plant is its succulent leaves and thick trunk(s). This is a plant that is a complete idea, minus any blooms. But that’s part of the charm—flowers as lagniappe.

Once you notice one jade plant, you notice they are everywhere. I don’t think you could go a single residential block in the East Bay without finding at least one, and probably 10 or 50. They might be the region’s single most popular plant, if you don’t count grass? (Not strongly evidenced, just a guess.) I find myself apologizing to beautiful specimens everywhere I go now. I’m sorry I couldn’t see you before, you absolute unit.

Here’s the thing, though: while succulents are very fashionable, the jade plant is … not. And it has not been for many years. I’m sure you know the house-being-flipped look: ornamental grasses, perhaps some rosette-y succulents, wood chips to cover the flaws. But never ever ever a jade plant.

Trends change; plants grow. So now, the jadescape is a living negative image of gentrification. If there’s a thick jade in the front yard (or hell strip or over by the trash can storage or half fallen over in a pot), you know that place probably has not changed hands for quiiiite a while.¹ Thick jadescape means old Bay Area, crystals aligned for a Raiders victory, forgotten spiritualities of shuttered second-wave coffee shops. But how’d they get there in the first place? When were jade plants so popular?

No one really tracks these things or writes histories about the growth and distribution of the plant varieties in northern California. But doesn’t the sturdy jade deserve it? I went back through newspaper archives and old books. Here’s the best I’ve been able to figure it.

Scientific name, Crassula ovata. Like many succulents, the jade plant is from southern Africa. I couldn’t find anything specific on when it entered wide distribution, but it rode in on a wave of orientalism. By 1923, House and Garden could say, "From every point of view, there could be few more attractive ornaments for a room than one of these Oriental jade plants, and may we not suppose that it would bring something of the enchantment of strange lands and mysterious temples?” Sadly, we may not suppose.

Fast forward to 1966 in Stockton, and a newspaper columnist related that “a friend of mine who is very interested in Oriental art and culture loves to display her jade plant in front of a fine hand-painted screen.” Elegante!

So, it was an “exotic plant” with a vaguely eastern gloss that could be had for $1.59 in a 4” pot. It was unkillable, tolerated (even loved) being forgotten, and could be propagated by crudely breaking off a branch and sticking it somewhere. Free jade, easier than free love.

And here’s the crux of the story. In the early 1970s, ecology had become a new way of seeing the world. City residents were inventing a new kind of relationship with other living things. This is the era that birthed the “fern bar,” macrame hangers, the open space movement, and visionary ecological art like Bonnie Ora Sherk’s “The Public Park” series, where she installed temporary parks inside urban infrastructure. Plant sales boomed in the groovy cosmopolitan places, including jade.

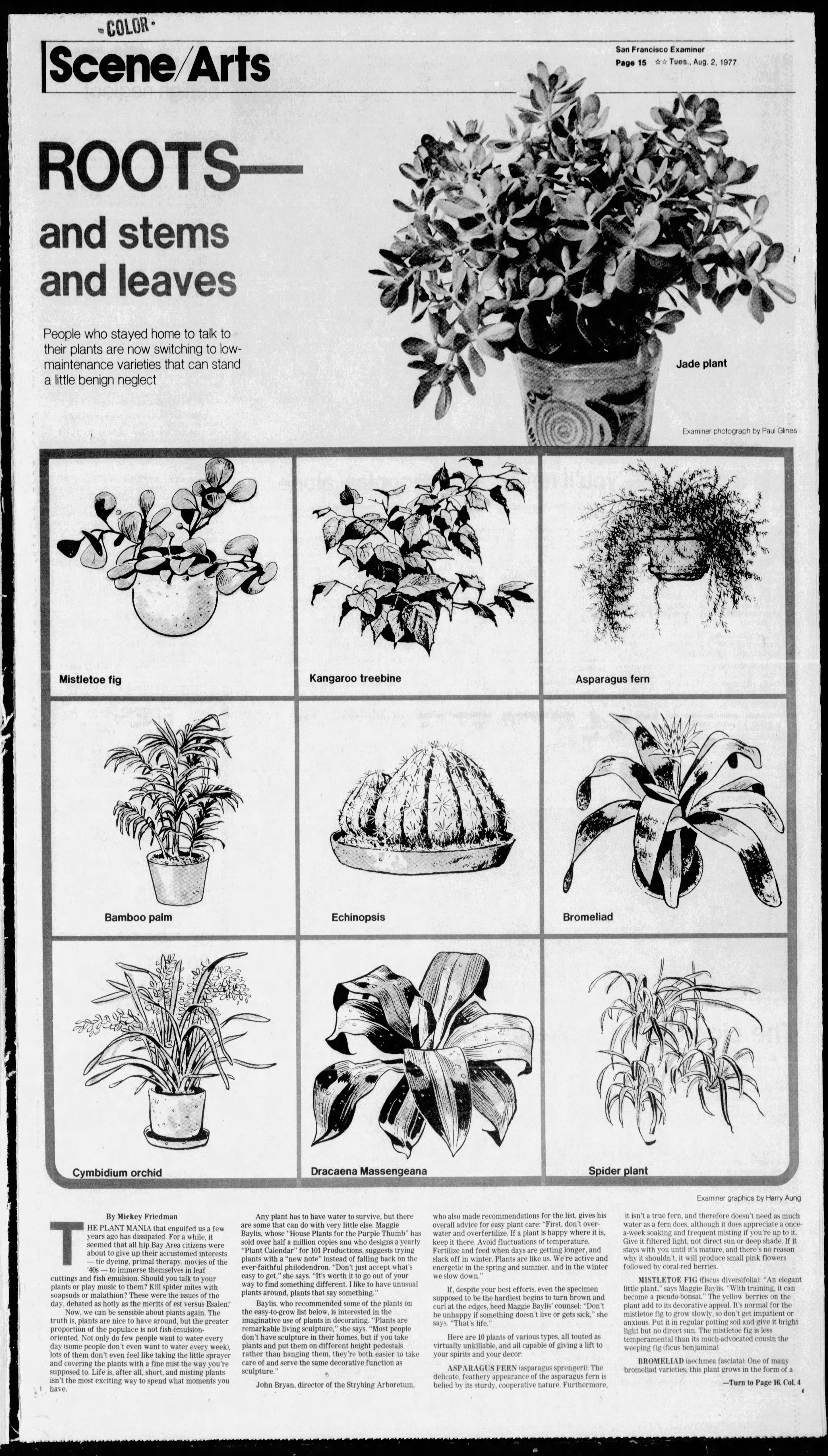

And then … the plant boom ended. You have to love this August 1977 lede in the San Francisco Examiner by Mickey Friedman, and its checklist of high 70s Bay Area references.

"The plant mania that engulfed us a few years ago has dissipated. For a while, it seemed that all hip Bay Area citizens were about to give up their accustomed interests—tie dyeing, primal therapy, movies of the '40s—to immerse themselves in leaf cuttings and fish emulsion. Should you talk to your plants or play music to them? Kill spider mites with soapsuds or malathion? These were issues of the day, debated as hotly as the merits of est versus Esalen. Now, we can be sensible about plants again. The truth is, plants are nice to have around, but the greater proportion of the populace is not fish-emulsion oriented."

But people didn’t necessarily want to go back to a plant-less life, Friedman argued. They just wanted easier plants, and what easier plant could there be than the jade? It went above the fold.

As time went by, jade plants ended up in odd places, tucked into forgotten corners, snipped into makeshift hedges, wrapped around a pole, thickening by the driveway, greening up the SRO. Our climate agreed with them. They thrived wherever no one was looking. They don’t need to be cared for, just left alone.

Jade plants propagate so easily that you just know a few really productive plants seeded whole blocks. In an interwoven place like Berkeley, maybe all the jade are distantly related, some ceramics auntie’s prize specimen multiplying yard-by-yard. Even generations removed, mustn’t the plants still retain a whiff, an essence of low-note earthiness? I hope so. We need it, we people of blue light hairlessness, of Zoom and Airspace and and emoji eggplants and bright airy kitchens.

In any case, I predict a jade resurgence.

¡CUTTINGS!

First, go see that Bonnie Ora Sherk show at Ft. Mason. It felt like discovering an ancestor of my thoughts and Oakland Garden Club. I mean, look at this photo that opens the show. We have a Forum show on it, too.

From the have-you-ever-wanted-to-be-a-flowing-syncytium department... A quote from The Lives of a Cell by Lewis Thomas: “Inflammation and immunology must indeed be powerfully designed to keep us apart; without such mechanisms, involving considerable effort, we might have developed as a kind of flowing syncytium over the earth, without the morphogenesis of even a flower.” What a lovely, disconcerting dream of the annihilation of self, no?

Berkeley alchemist Mandy Aftel’s book Fragrant sent me to look up Herman Hesse, who has a wonderfully current and archaic view of these nonhuman teachers. There’s a whole book of his work on trees, and it’s really good. (Next up, I may have to go read the German romantics that he loved.) Here’s a taste: “Trees are holy. If you know how to talk to them, how to listen to them, you will learn the truth. They preach not doctrines and rules: they preach, with no concern for details, the primal law of life. A tree says: Hidden in me is a seed, a spark, a thought. I am life from eternal Life.”

I desperately want to go to Golden Sardine in North Beach. Cool North Beach lives!

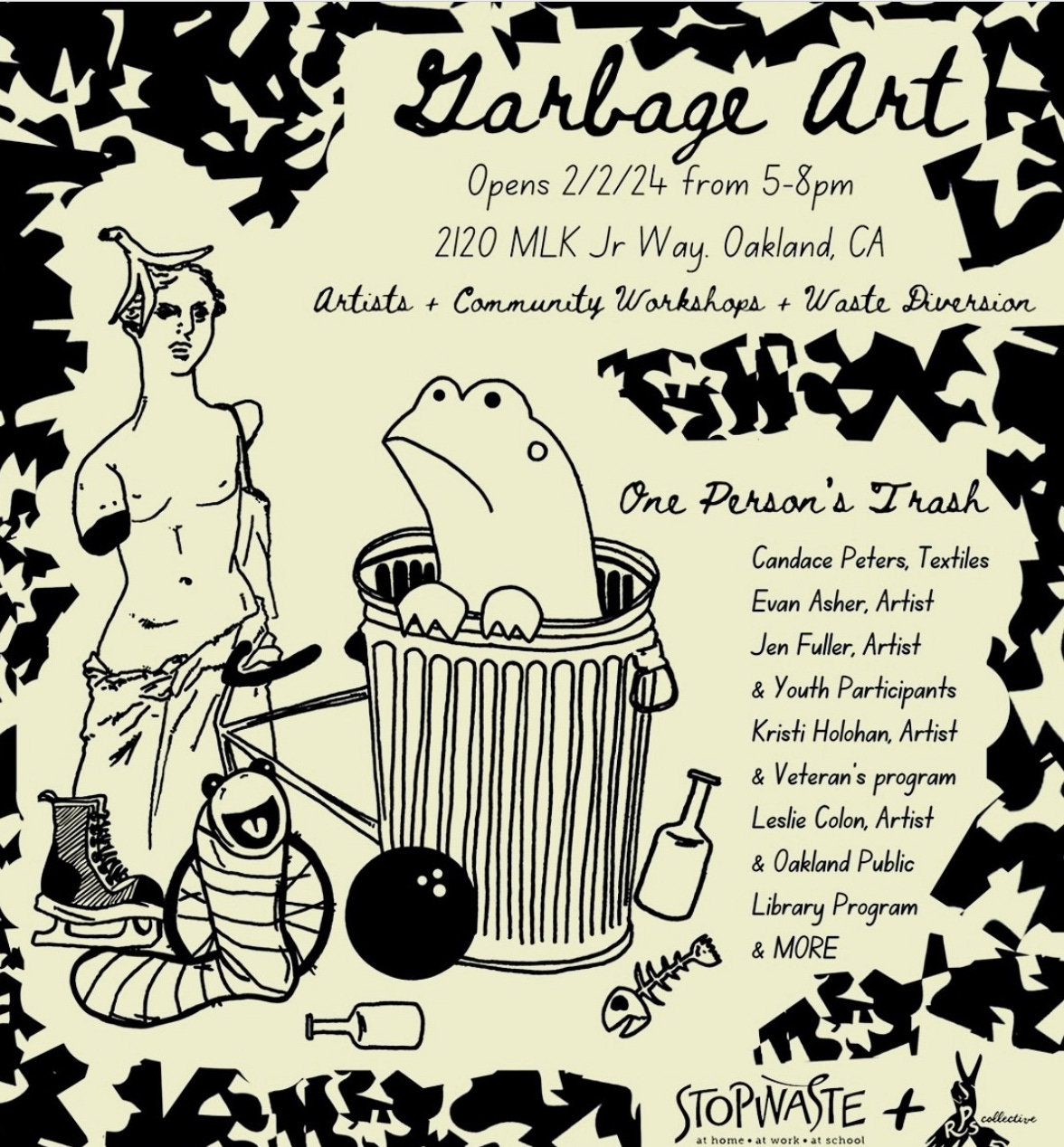

A show opens Friday at RPS Collective (2120 MLK in Oakland) called One Person’s Trash. A bunch of artists working with waste streams. The poster is fantastic.

Also on Friday, 2727 in Berkeley has a multidisciplinary group show opening called Same Boat, “an evening of music, poetry, & art about interdependence”

The CODEX art book fair starts Sunday, February 4. It’s gonna be at the Kaiser Center in Oakland.

There’s so much I want to tell you about Soviet pomegranates, but I’m out of space in this edition. But please, if you absolutely must hear more about Soviet Pomegranates, do leave a comment.

You're currently a free subscriber to oakland garden club. For the full experience, upgrade your subscription.