|

|

“Greeting to Spring (Not Without Trepidation)” by Robert Lax from Tertium Quid. © Stride Publications, 2005.

ORIGINAL TEXT AND AUDIO - 2017

Today is the birthday of the actor and director Lionel Barrymore, born in Philadelphia (1878). He was born Lionel Blythe — “Barrymore” was his parents’ stage name. Maurice Blythe and Georgina Drew Blythe were both actors, and raised their kids to tread the boards as well. Lionel was the oldest, and his sister, Ethel, and brother, John, also became successful thespians. Lionel appeared in his first play at the age of six, but he didn’t seem to have the knack of it. He went through a rebellious phase and decided to study art in Paris instead.

He returned to acting just as the new film industry was getting underway. His first movie was The New York Hat (1912), for which he received 10 dollars a day. Two young actresses named Mary Pickford and Lillian Gish were his co-stars, and it was the first script written by Anita Loos. He starred in and directed a number of silent movies, and signed a deal with MGM in 1925. He appeared in many popular films of the 1930s, including Grand Hotel (1932), Dinner at Eight (1933), and You Can’t Take it With You (1938). But he had arthritis, and by the end of the decade it was so bad that he had to use a wheelchair. He and his wheelchair appeared in the perennial classic It’s a Wonderful Life (1946); Barrymore played Henry Potter, the mean-spirited banker who was ranked number six on the American Film Institute’s list of the 50 greatest villains in American movies. Barrymore also directed several movies, composed musical scores, and played Ebenezer Scrooge in an annual radio play of A Christmas Carol for many years.

Lionel Barrymore, who once said: “Half the people in Hollywood are dying to be discovered and the other half are afraid they will be.”

It’s the birthday of the writer who once said, “All I want is to be the Jane Austen of South Alabama.” That was Harper Lee (1926), the author of the classic novel To Kill a Mockingbird (1960), which introduced the characters of Scout Finch and her father, lawyer Atticus Finch, to the world. The novel examined race relations in the American south and is still required reading in many high schools. It took Lee several drafts and two and half years to write the book, which won the Pulitzer Prize. It’s since sold over 40 million copies and has never been out of print.

Harper Lee grew up in Monroeville, Alabama, and except for when she moved to New York City for a few years after college, that’s where she lived all her life. Her childhood best friend was Truman Capote, who would grow up to be a writer, too. Lee’s father was a prominent lawyer and he bought Lee and Capote an old Underwood typewriter and they’d spend hours dictating stories to one another. Capote wrote a novel called Other Voices, Other Rooms (1948), and based the character of Idabel Thompkins on Lee. When Lee wrote To Kill a Mockingbird, she based the character of Dill on Capote. She even helped Capote with the extensive research for his nonfiction book In Cold Blood (1966), a story about a real-life murder, but they later had a falling out.

To Kill a Mockingbird, which was originally titled Atticus, made Harper Lee famous, but she didn’t like doing interviews or having her photo taken. She said, “Well, it’s better to be silent than to be a fool.” Not everyone was a fan of the novel, though. Her fellow writer Flannery O’Connor snipped, “It’s interesting that all the folks that are buying it don’t know they’re reading a child’s book.”

It’s the birthday of playwright Robert Anderson, born in New York City (1917) and best known for Tea and Sympathy, about the relationship between a prep school boy and his housemaster’s wife. It debuted on Broadway in 1953, directed by Elia Kazan, and has gone on to be a staple of high school theater productions.

Anderson based the play on his own experiences at elite private school Phillips Exeter, where he, too, fell in love with an older woman. After sunbathing with a male professor, the student in the play faces accusations of homosexuality from his peers. Attempting to shield him from harm, the lonely wife ends up beginning a romantic relationship with the boy. It took Anderson years to finish the play, and then to even get it produced, and he was once so despondent about his writing that he tacked a sign above his writing desk that read, “Nobody asked you to be a playwright.”

It was one of the first plays to tackle the subject of sexual orientation and prejudice, which was taboo at the time. Tea and Sympathy has become famous for its bittersweet, final line, when the wife tells the young man, “Years from now, when you speak of this, and you will, be kind.” Actress Deborah Kerr, fresh from kissing Burt Lancaster in the sand in the film From Here to Eternity (1953), played the housemaster’s wife. The play was a huge hit, and Kerr even starred in the film version.

Robert Anderson went on to write several more plays, including You Know I Can’t Hear You When the Water’s Running (1967), consisting of four one-act comedies. It was such a hit that it ran for more than 700 performances and ushered in an era of onstage nudity. Actor Martin Balsam did the honors.

About being a playwright, Robert Anderson once said, “You can make a killing in the theater, but not a living.”

It’s the birthday of one of the founders of photojournalism, Erich Salomon, born in Berlin, Germany (1886). Photography was his hobby, and he bought one of the first cameras with a high-speed lens, which could take pictures in dim light. He hid the camera in an attaché case and photographed famous people at parties without their knowing it. As a result, his pictures seemed unusually relaxed and unposed, in comparison to those of other photographers of his time. The pictures were wildly popular and published in magazines around Europe. A writer for the London Graphic, referring to Salomon, coined the phrase “candid camera.”

Today is the birthday of poet and human rights activist Carolyn Forché, born in Detroit (1950). Her mother had also written and published poetry, and she encouraged Carolyn to follow that dream — but also to get a day job. She’s known as a political poet, but she prefers to call herself a “poet of witness,” and has said, “What I’m really interested in is the human condition throughout the world.” She traveled to El Salvador in 1978; she toured the country, which was in the middle of a civil war, and wrote about what she saw. With the help of Margaret Atwood, she published The Country Between Us (1981), and it became a best-seller. She also published an anthology called Against Forgetting: Twentieth-Century Poetry of Witness in 1993. Nelson Mandela called the book “a blow against tyranny, against prejudice, against injustice.” This year, Forché was awarded a Windham-Campbell Prize from Yale, an award of $160,000. She will use the money to finish her memoir. She’ll also complete her fifth poetry collection, which is called In the Lateness of the World, and includes poems about the current refugee crisis.

Be well, do good work, and keep in touch.®

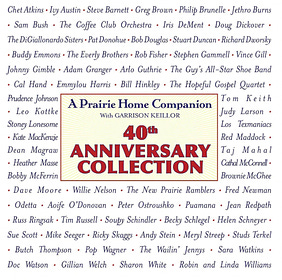

A Prairie Home Companion 40th Anniversary (4 CD set)

You’re a free subscriber to The Writer's Almanac with Garrison Keillor. Your financial support is used to maintain these newsletters, websites, and archive. Support can be made through our garrisonkeillor.com store, by check to Prairie Home Productions P.O. Box 2090, Minneapolis, MN 55402, or by clicking the SUBSCRIBE button. This financial support is not tax deductible.