|

|

"When the Vacation is Over for Good" by Mark Strand, from New and Selected Poems. © Alfred A. Knopf, 2009.

ORIGINAL TEXT AND AUDIO - 2011

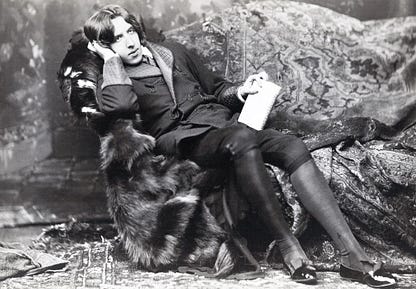

It's the birthday of the writer who said: "A man's face is his autobiography. A woman's face is her work of fiction." That's Oscar Wilde, born in Dublin (1854). He wrote just one novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890), and in the preface to it, he wrote: "All art is quite useless." A student at Oxford named Bernulf Clegg was intrigued by that statement, and he wrote to Wilde and asked him what he meant by it.

Wilde responded:

"My dear Sir

Art is useless because its aim is simply to create a mood. It is not meant to instruct, or to influence action in any way. It is superbly sterile, and the note of its pleasure is sterility. If the contemplation of a work of art is followed by activity of any kind, the work is either of a very second-rate order, or the spectator has failed to realize the complete artistic impression.

A work of art is useless as a flower is useless. A flower blossoms for its own joy. We gain a moment of joy by looking at it. That is all that is to be said about our relations to flowers. Of course man may sell the flower, and so make it useful to him, but this has nothing to do with the flower. It is not part of its essence. It is accidental. It is a misuse. All this is I fear very obscure. But the subject is a long one.

Truly yours,

Oscar Wilde

It's the birthday of German novelist Günter Grass, born in Danzig, Germany (1927), which is now Gdansk, Poland. He has written many novels, but is probably most famous for his first, The Tin Drum (1959), about a three-year-old boy who refuses to grow up so that he can escape the horrors of Nazi Germany.

Grass's parents ran a grocery store, but week after week they barely broke even. All of Günter's friends got allowances, but he never got anything. Finally, after he had pestered his mother so many times she couldn't stand it anymore, she gave him the list of everyone who bought food on credit and owed the store money, and told her son to walk around the town asking them to repay their debt; if you can collect the money, she said, I'll give you a percentage of it. So he became a successful debt collector — and finally got an allowance — when he was about 10 years old. Also when he was 10, he joined the Jungvolk, the junior version of Hitler's youth group, and then became part of Hitler Youth. He volunteered for submarine service, and at the age of 17 he was drafted into the Waffen-SS, Hitler's elite corps.

Throughout his career, it was public knowledge that Grass was part of the Hitler Youth and the army, but the fact that he was a member of the Waffen-SS did not emerge until he published his memoir Peeling the Onion in 2007. People were outraged. For many years he had been considered a moral voice of Germany in regard to the era of Naziism, and the fact that he had kept this piece of his past hidden caused many people to question everything he had ever said. In 1985, Grass had said it was a "defilement of history" when Ronald Reagan and Helmut Kohl laid wreaths at a cemetery that turned out to contain the graves of Waffen-SS soldiers, and now that he revealed himself to have been one, he was quickly labeled a hypocrite. Critics grew so angry that they called on him to return the Nobel Prize in literature, which he had won in 1999. They thought he should be stripped of honorary titles and publicly apologize. The controversy shocked and saddened Grass. He said: "The public's reaction hit me very hard. It was unexpected. I couldn't sleep at night. It was Tristram Shandy who helped me get over it all, to put everything in perspective. It made me laugh again, even though I didn't have anything to laugh about. I saw Laurence Sterne dealing with his critics in the book and I admired the sharp, precise and witty way he did it."

In Peeling the Onion he wrote: "An imprecise memory sometimes comes a matchstick's length closer to the truth, albeit along crooked paths. It is mostly objects that my memory rubs against, my knees bump into, or that leave a repellent aftertaste: the tile stove ... the frame used for beating carpets behind the house ... the toilet on the half-landing ... the suitcase in the attic ... a piece of amber the size of a dove's egg ... If you can still feel your mother's barrettes or your father's handkerchief knotted at four corners in the summer heat or recall the exchange value of various jagged grenade- and bomb splinters, you will know stories — if only as entertainment — that are closer to reality than life itself."

His other books include Cat and Mouse (1961), Dog Years (1963), and Crabwalk (2002).

It's the birthday of Eugene O'Neill, born in New York City (1888). His father, James O'Neill, was a traveling actor who played the lead in The Count of Monte Cristo more than 6,000 times over the course of 30 years. Eugene O'Neill described his father: "He was a strong, cello-voiced man who quoted Shakespeare like a deacon quotes the Bible." But he also said, "There's no secret about my father and me. Whatever he wanted, I wouldn't touch with a 10-foot pole."

Eugene was born in a hotel room, and his father went back on tour two days after the birth. For much of his childhood, O'Neill accompanied his father. He said, "My early experience with the theater through my father really made me revolt against it. As a boy I saw so much of the old, ranting, artificial, romantic stage stuff that I always had a sort of contempt for the theater." Then in 1907, when O'Neill was 18 years old, he saw the Russian actress Alla Nazimova star in Henrik Ibsen's Hedda Gabler at the Bijou Theater in New York. He said, "The experience discovered an entire new world of the drama for me. It gave me my first conception of a modern theater where truth might live." Hedda Gabler ran for 32 performances, and O'Neill went to 10 of them.

He went on to write 50 plays, including The Hairy Ape (1921), Desire Under the Elms (1924), The Iceman Cometh (1939), and Long Day's Journey Into Night (1941).

He said: "Keep on writing, no matter what! That's the most important thing. As long as you have a job on hand that absorbs all your mental energy, you haven't much worry to spare over other things. It serves as a suit of armor."

Be well, do good work, and keep in touch.®

Why Subscribe? The Writer’s Almanac Anniversary newsletter that you receive here is free. The Subscription button is one way that you can show financial support of this project.

You can also send a Support us through our store - CLICK HERE

Or mail us a check: Prairie Home Productions, P.O. Box 2090, Minneapolis, MN 55402

You’re a free subscriber to The Writer's Almanac with Garrison Keillor. Your financial support is used to maintain these newsletters, websites, and archive. Support can be made through our garrisonkeillor.com store, by check to Prairie Home Productions P.O. Box 2090, Minneapolis, MN 55402, or by clicking the SUBSCRIBE button. This financial support is not tax deductible.