|

|

“Windows is Shutting Down” by Clive James from Opal Sunset. © W. W. Norton & Company, 2008.

ORIGINAL TEXT AND AUDIO - 2016

It’s the birthday of English crime novelist and playwright Agatha Christie (1890), the best-selling novelist of all time. Christie’s books have sold more than 2 billion copies around the world and been translated into more than 103 languages.

She was born Mary Clarissa Agatha Miller in Torquay, Devon, to an upper-middle-class family. She was home-schooled by her mother until she was 16, when she was sent to school in Paris to study piano and mandolin. Her father died when she was young, which threw the family into financial upheaval. Rice pudding became a frequent meal, but Christie still described her childhood as “gloriously idle.” She adored her mother, who dabbled in Unitarianism and theosophy, made her own dolls and doll furniture, made up ghost stories with her sisters and mother, and favored the nonsensical books of Edward Lear and Lewis Carroll.

Christie worked as a nurse at the Torquay Hospital during World War I, learning much about the poisons that would later populate her novels. She began writing stories, mostly about spiritualism and the paranormal. She set her first novel, Snow Upon the Desert, in Cairo and used the pen name “Monosyllaba.” The book was rejected by numerous publishers. She tried again with a book called The Mysterious Affair at Styles (1920), which featured an extravagantly mustached Belgian detective named Hercule Poirot. The book was a hit, and Christie was off and running. Hercule Poirot would be featured in more than 33 of Christie’s novels, though she admitted she found Poirot “insufferable and an egocentric creep.” She actually killed off Poirot in a novel titled Curtain: Poirot’s Last Case, in the early 1940s, and had it stored in a bank vault to safeguard it from Nazi destruction during World War II. When the book was published in 1975, the New York Times ran Hercule Poirot’s obituary on the front page.

Agatha Christie’s formula was simple: assemble eight or nine people on a snowbound train, a girls’ school, or in a remote country house and add a murder. She had a strong dislike for guns, so she devised other methods to dispatch her victims, poison being the most common. In one novel, a child dies by bobbing for apples. In another, a character is electrocuted while executing a specific chess move. Christie stored a corpse with tennis rackets at a club and once had her detective squirt soapy water to subdue a murderer. She often employed red herrings and double bluffs. In one book, the killer turns out to be a dead man. In another, the killer is a child. And in another, it turns out that all 12 suspects have committed the crime, together.

Christie created the character of Jane Marple, an elderly spinster, for the 1927 short story, “The Tuesday Night Club,” which appeared in Royal Magazine. Marple appears in 12 Christie novels, including The Thirteen Problems (1932). Marple is a nosy old woman and amateur detective living in the village of St. Mary Mead. Christie said Marple was, “the sort of old lady who would have been rather like some of my step-grandmother’s Ealing cronies — old ladies whom I have met in so many villages where I have gone to stay as a girl.”

Agatha Christie’s play The Mousetrap, originally written as a radio sketch in honor of Queen Mary’s 80th birthday, is the world’s longest running play. It was first staged in 1952 and has been running ever since. Agatha Christie was made a Dame of the British Empire in 1971 and died in 1976. Her books include Murder on the Orient Express (1934), Death on the Nile (1937), and The Mirror Crack’d from Side to Side (1962).

When asked about her writing method, Christie responded, “The disappointing truth is, I haven’t much method.” She worked out her plots in school exercise books, making lists of victims, culprits, and MOs, and then picking the best combinations. For most of her life, she pumped out one novel per year, admitting that she often felt like “a sausage machine.”

On writing, she said, “Three months seems to me to be quite reasonable to finish a book, if you can get right down to it.”

On this date in 1963, a bomb went off in the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. Birmingham was one of the most segregated cities in the country, and was a key battleground in the Civil Rights Movement. The church was a frequent meeting place for leaders of the movement, including James Bevel, Ralph David Abernathy, Fred Shuttlesworth, and Martin Luther King Jr. It was the fourth bombing in Birmingham in as many weeks, following a move to integrate the city’s public schools.

On Sunday morning, September 15, a turquoise and white 1957 Chevy pulled up outside the church. A white man by the name of Robert Chambliss got out and placed a box under the church steps. The box was loaded with dynamite, and it exploded just before 10:30 in the morning. Four schoolgirls — Cynthia Wesley, Carole Robertson, Addie Mae Collins, and Denise McNair — were killed in the explosion. More than 20 other churchgoers were injured. The UPI news report described the aftermath: “Dozens of survivors, their faces dripping blood from the glass that flew out of the church’s stained glass windows, staggered around the building in a cloud of white dust raised by the explosion. The blast crushed two nearby cars like toys and blew out windows blocks away. [...] Parts of brightly painted children’s furniture were strewn about in one Sunday school room, and blood stained the floors. Chunks of concrete the size of footballs littered the basement.”

Chambliss, a member of the Ku Klux Klan, was convicted of possessing dynamite without a permit, and was sentenced to a $100 fine and six months’ jail time. He was found not guilty in the murders of the four girls. A later investigation revealed that the FBI, under the direction of J. Edgar Hoover, had suppressed key evidence against Chambliss. He was retried in 1973, found guilty, and sentenced to life in prison. And in 2000, three men who had been Chambliss’s accomplices were also named. One man had already died, but the others were tried and convicted in 2001 and 2002.

Be well, do good work, and keep in touch.®

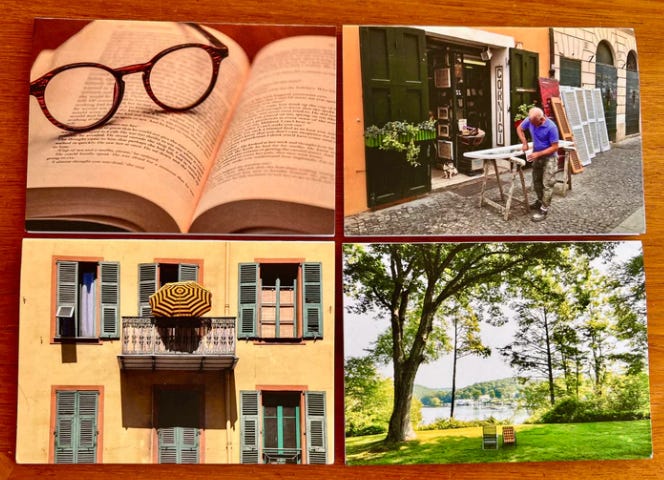

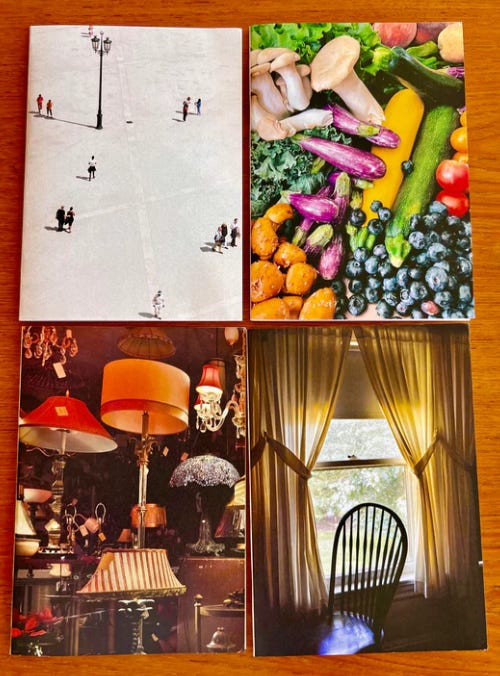

CHECK out our BRAND NEW notecards

Friendship Sonnets written by Garrison Keillor

You’re a free subscriber to The Writer's Almanac with Garrison Keillor. You can make donations in different ways to support this service. Donate through our garrisonkeillor.com store, send a check to Prairie Home Productions, P.O. Box 2090, Minneapolis, MN 55402 or simply hit the SUBSCRIBE button.