|

|

"Brown Penny” by William Butler Yeats.

ORIGINAL TEXT AND AUDIO - 2017

On this date in 1799, French soldiers in Napoleon’s army discovered the Rosetta Stone at a port town on Egypt’s Mediterranean coast. They were digging a foundation for a fort when they came upon a slab of rock about 4 feet high and 2 and half feet wide, 11 inches thick and weighing 1,700 pounds. What caught the soldiers’ attention was the writing on the stone, in three different scripts: ancient Greek, demotic, and Egyptian hieroglyphics.

Scholars could read and understand the ancient Greek. The second script, demotic, was an Egyptian language that was spoken and written at the time that the Rosetta Stone was carved in 196 B.C., and contemporary scholars understood some bits and pieces of it. But Egyptian hieroglyphics had been a “dead” language for nearly 2,000 years. All around Egypt there abounded pyramids and temples with thousands of hieroglyphic characters carved into the walls, but no one could figure out what the inscriptions meant. When linguists realized that the three texts on the Rosetta Stone all said the same thing, they knew that they had a key to breaking the hieroglyphic “code” at last. A British scholar made good progress on figuring out the demotic text by 1814, and then the French scholar Jean-François Champollion worked out the hieroglyphics between 1822 and 1824.

The Rosetta Stone had been created in 196 B.C. on the orders of Ptolemy V, a Greek emperor who ruled Egypt during the Hellenistic period. It begins with a lofty address, where Ptolemy acknowledges by name some ancestors and gods. He goes on to praise his administration’s good deeds and himself at length, and then he announces tax breaks for the non-rebellious Egyptian temple priest class. He also gives instructions for the building of temples.

The Rosetta Stone has been exhibited at London’s British Museum since 1802 — with the exception of a two-year period near the end of World War I. The stone was moved to an underground railway station in Holborn to protect it from German bombs.

On this day in 1898, novelist Émile Zola fled France in the wake of what would become known as the “Dreyfus Affair.” Zola was one of France’s best-known writers and a leading intellectual. He had already completed his enormously successful 20-volume series Les Rougon-Macquart when he decided to write what would prove to be an inflammatory letter to the president of France, condemning the secret military court-martial of Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a French artillery officer of Jewish descent, who was accused of selling secrets to the German army and banished to Devil’s Island in South America. Evidence had surfaced of Dreyfus’ innocence, but the French military suppressed it.

Zola’s letter ran on the front page of the Parisian newspaper L’Aurore under the heading “J’Accuse!” (“I accuse!”) It read, in part: “I repeat with the most vehement conviction: truth is on the march, and nothing will stop it. Today is only the beginning, for it is only today that the positions have become clear: on one side, those who are guilty, who do not want the light to shine forth, on the other, those who seek justice and who will give their lives to attain it. I said it before and I repeat it now: when truth is buried underground, it grows and it builds up so much force that the day it explodes it blasts everything with it. We shall see whether we have been setting ourselves up for the most resounding of disasters, yet to come.”

Zola’s letter provoked national outrage on both sides of the issue, among political parties, religious organizations, and others. Accused of libel and sentenced to one year in prison, he fled to England for a year. His letter forced the military to address the Dreyfus Affair in public. Dreyfus was released and exonerated. Zola died four years later. His letter prompted the 1902 law that separated church and state in France and ushered in the political liberalization of France.

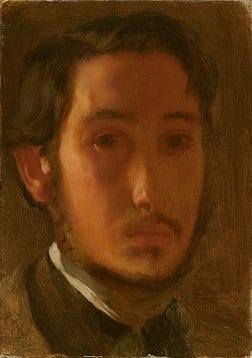

It’s the birthday of French Impressionist Edgar Degas, born in Paris (1834), best known for his paintings and pastels of ballet dancers and his bronze sculptures of ballerinas and racehorses. After he became completely blind in one eye, and nearly so in the other, he began to work in sculpture, which he called “a blind man’s art.” Degas remained a bachelor his entire life, saying, “There is love and there is work, and we only have one heart.”

It’s the anniversary of the, organized in Seneca Falls, New York, in 1848. It was organized by Elizabeth Cady Stanton and her friend Lucretia Mott. They had been getting together frequently to talk about the abuses they suffered as women, and they finally decided to have a public meeting to discuss the status of women in society. At the meeting, on this day in 1848, they drew up a declaration, which said in part, “The history of mankind is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations on the part of man toward woman.” Elizabeth Cady Stanton read the declaration and then made a radical suggestion that the document should also demand a woman’s right to vote. At that time, no women were allowed to vote anywhere on the planet. And many of the other women there objected to the idea. They thought it was impossible.

It was on this day in 1954 that the first part of the Lord of the Rings trilogy came out, The Fellowship of the Ring. It was the sequel to J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit, which was published in 1937 (books by this author). Tolkien had written The Hobbit for his own amusement and didn’t expect it to sell well. It’s the story of Bilbo — a small, human-like creature with hairy feet — who goes on an adventure through Middle Earth and comes back with a magical ring.

J.R.R. Tolkien once wrote: “I am in fact a hobbit in all but size. I like gardens, trees, and unmechanized farmlands. I smoke a pipe, like good, plain food, detest French cooking [...] I am fond of mushrooms, have a very simple sense of humor [...] go to bed late and get up late (when possible). I do not travel much.”

The Hobbit sold pretty well, partly because C.S. Lewis gave it a big review when it came out. And so Tolkien’s publisher asked for a sequel. Tolkien decided the new book would be about Bilbo’s nephew Frodo, but for a long time he had no idea what sort of adventure. Finally, he decided it would be about the magical ring, though the ring had not been such an important part of The Hobbit.

Tolkien spent the next 17 years working on The Lord of the Rings. He was a professor at Oxford. He had to write in his spare time, usually at night, sitting by the stove in the study in his house.

He was well into his first draft by the time World War II broke out in 1939. He hadn’t set out to write an allegory, but once the war began, he started to draw parallels between the war and the events in his novel: the land of evil in The Lord of the Rings, Mordor, was set east of Middle Earth, just as the enemies of England were to the east.

The book became more and more complicated as he went along. It was taking much longer to finish than he’d planned. He went through long stretches where he didn’t write anything. He thought about giving up the whole thing. He wanted to make sure all the details were right, the geography, the language, the mythology of Middle Earth. He made elaborate charts to keep track of the events of the story. His son Christopher also drew a detailed map of Middle Earth.

Finally, in the fall of 1949, he finished writing The Lord of the Rings. He typed the final copy himself sitting on a bed in his attic, typewriter on his lap, tapping it out with two fingers. It turned out to be more than a half million words long, and the publisher agreed to bring it out in three volumes. The first came out on this day in 1954. The publisher printed just 3,500 copies, but it turned out to be incredibly popular. It went into a second printing in just six weeks. Today more than 150 million copies have been sold around the world. It is considered one of the best-selling books of all time.

Be well, do good work, and keep in touch.®

Living with Limericks Softcover

You’re a free subscriber to The Writer's Almanac with Garrison Keillor. Your financial support is used to maintain these newsletters, websites, and archive. Support can be made through our garrisonkeillor.com store, by check to Prairie Home Productions P.O. Box 2090, Minneapolis, MN 55402, or by clicking the SUBSCRIBE button. This financial support is not tax deductible.