|

One night last spring, my apartment’s buzzer went off. Meg Elison, an award-winning science fiction writer, was waiting downstairs. She’d agreed to come by for a strange experiment.

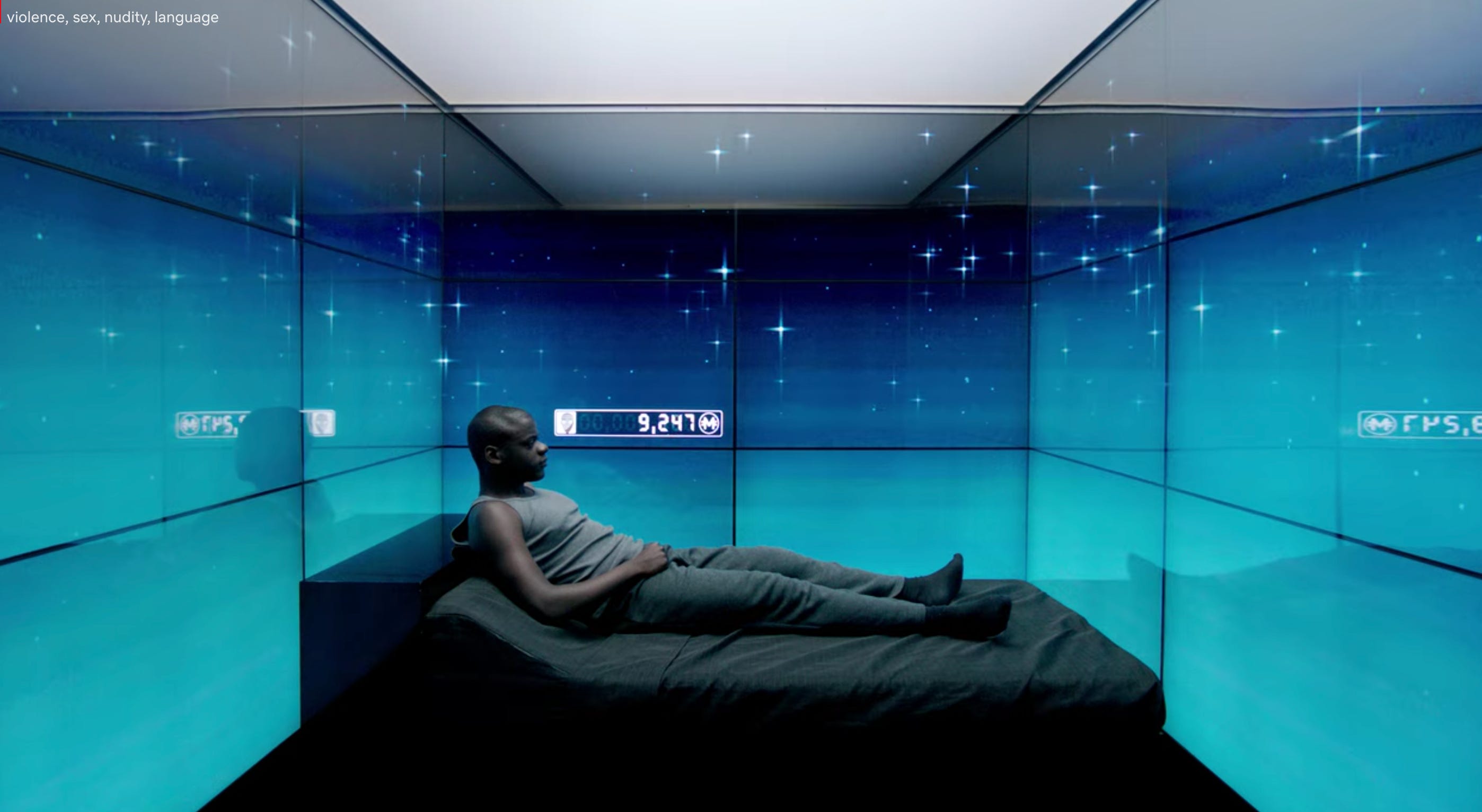

I was nearly finished with my book, Always Day One, when I asked Elison to visit for dinner. Wael Ghonim, a leader of the social media-fueled Arab Spring, would join as well. Over falafel and kebab, the three of us would discuss the technology I planned to cover in the book, and imagine it taken to its most dystopian ends. We’d go full Black Mirror.

Always Day One covers the tech giants’ work culture, so we weren’t talking about killer robots; this was more about collaboration tools and process automation technology. But still, I came away from the experience believing every tech company should hire a science fiction writer, at least if they’re interested in keeping their products safe.

A void of creative, dystopian thinking has caused serious problems in the tech world, especially among the tech giants. Filled with techno-optimists, these companies routinely miss problems they should anticipate. Google didn’t imagine YouTube would radicalize users, Facebook didn’t expect a foreign power would exploit its service, Amazon didn’t think its “Amazon’s Choice” label would recommend malfunctioning thermometers, and so on.

More than product problems, these are planning problems. Some dark thinking could help the tech giants anticipate where things can go wrong, enabling them to prepare before their crises explode. But instead, they build for the best-case scenario. (Amazon employees, for instance, write up ideas for new products in six-page narratives that always end happily.) So when things break down, they get bad quickly.

Elison, Ghonim, and I gathered that night to poke holes in my largely-optimistic assessment of the tech giants’ internal technology and processes (apologies for the narrative violation). These systems have helped Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google, and Microsoft dominate our economy, and I was about to recommend the rest of us coopt them. But first, it was important to see where they could go wrong.

As we let our imaginations run wild, our attention turned toward Google’s internal collaboration tools. Google’s built an array of technology that helps its employees know what’s going on everywhere. It has an internal meme board, an active network of listservs, a tool to ask questions of company leadership called Dory (named after the forgetful fish in Finding Nemo), and unprecedented transparency for a company its size. These tools help its employees effectively build products across divisions (see: Google Assistant).

In the heady days of 2018, Google’s employees also used these tools to organize and protest. They spoke out against the company selling artificial intelligence technology to the military and walked out over its bungling of sexual misconduct claims. Their actions changed Google for the better.

But when we started to imagine how this type of technology could be used for harm, things got dark. Led by Elison, we settled on a scenario where a government plants an operative inside a company with similar tools. The operative uses the tools to rally colleagues against one of the government’s enemies. Inspired by the movement, another employee with access to sensitive information exposes the enemy’s location. Then the government kills its adversary.

Unbeknownst to us, a similar scenario was unfolding inside Twitter. A few months after our dinner, the FBI alleged that people close to the Saudi royal family recruited two Twitter employees who then accessed Saudi dissidents’ private data without authorization. What happened to those dissidents is unclear.

Not expecting foreign entities to infiltrate its workforce, Twitter left its systems open for abuse. Then, after the fact, it patched up its vulnerabilities. “We have made changes to our backend systems, our employee training, and our security and infrastructure to guard against this type of situation,” a Twitter spokesman told me earlier this year.

These types of fixes don’t have to come too late. Perhaps having someone like Ellison on staff would’ve prevented the ugly scenario, or at least mitigated the harm.

This week on the Big Technology Podcast: Ex-Amazon VP Tim Bray

Former Amazon VP Tim Bray joins the Big Technology podcast this week. In May, Bray published a stunning blog post saying he would no longer work for Amazon after it fired employees who spoke up for its workers’ rights. “Firing whistleblowers,” he wrote, is “evidence of a vein of toxicity running through the company culture. I choose neither to serve nor drink that poison.”

We cover a good deal of ground in the conversation, including what it felt like to leave a job he loved, how white-collar and blue-collar workers are treated differently, and why Bray wants to break up the tech giants (yes, including his former employer). For someone who was so senior inside a tech giant, Bray was refreshingly candid and open.

You can listen and subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and Overcast. And you can read the transcript on OneZero. Bray also just started his own podcast. Box CEO Aaron Levie is up next week.